He’d been experimenting with cocaine. He wasn’t living at home anymore and he was ignoring every frantic voicemail his father left him. He was apathetic and devoid of motivation. Mark — a Palo Alto High School senior whose name has been changed to protect his identity, as with the names of all students in this story — spent the summer before junior year sliding deeper and deeper into his drug addiction.

He’d been experimenting with cocaine. He wasn’t living at home anymore and he was ignoring every frantic voicemail his father left him. He was apathetic and devoid of motivation. Mark — a Palo Alto High School senior whose name has been changed to protect his identity, as with the names of all students in this story — spent the summer before junior year sliding deeper and deeper into his drug addiction.

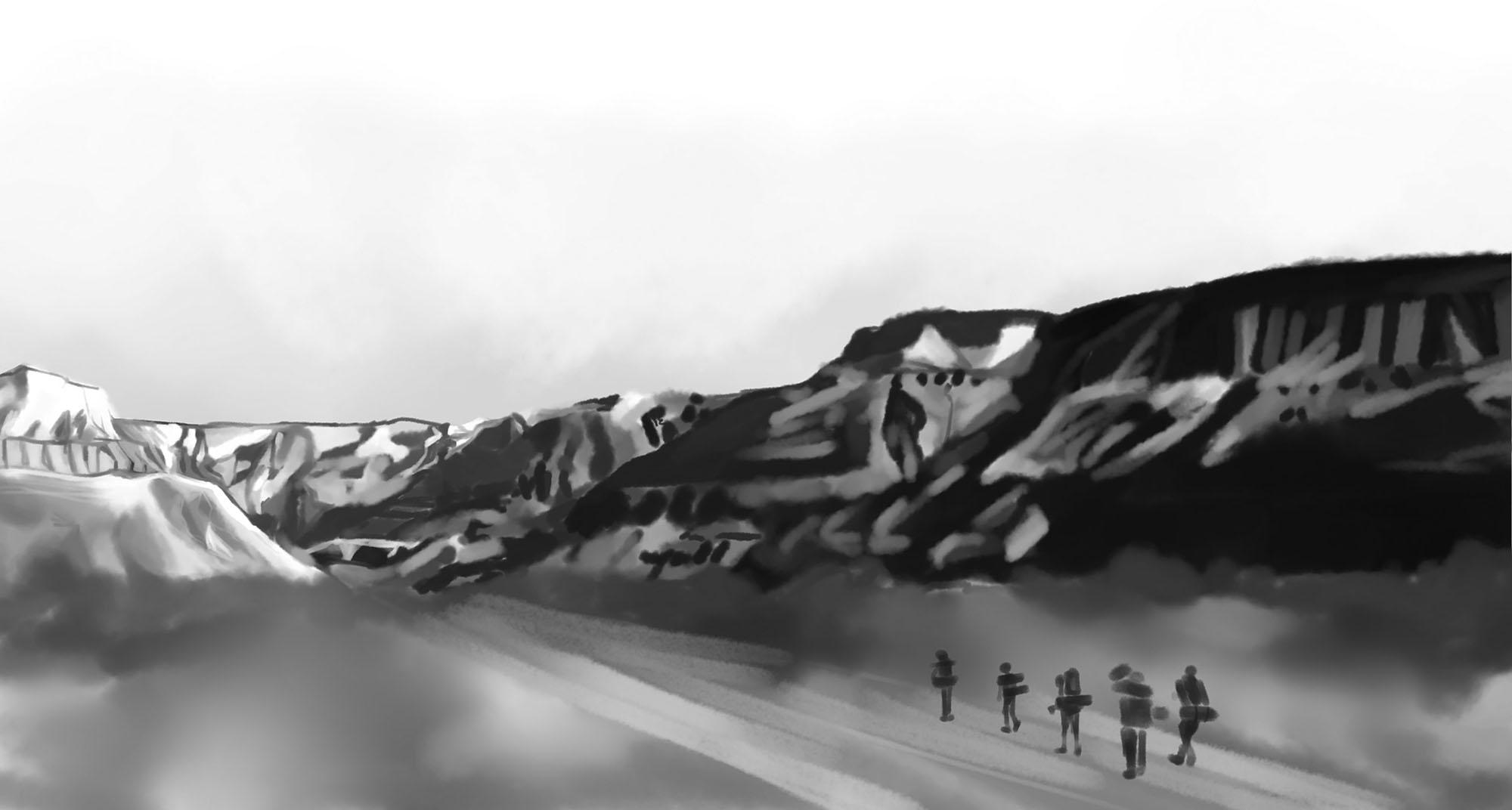

By the time school started back up again, Mark was hooked, forcing his family to seek help. After 12 days in a mental hospital, Mark was taken to Elements Wilderness Program in Huntington, Utah, where he would spend the next eight weeks surrounded by nature, detaching himself from the substances he had depended on for so long.

Wilderness therapy programs like the one that Mark attended are a non-traditional response to health issues like addiction, misbehavior and mental health. This comprehensive approach to addressing such issues, however, requires significant amounts of funding, often coming straight from families’ pockets in the form of hefty tuitions. While scholarships do exist, some programs can cost as much as $400 per day, and many insurance policies only cover the therapeutic component of these treatments. Yet, as the health care policy in our country is revised, the limited coverage that exists currently for wilderness therapy is becoming further constrained. As such, adolescents suffering from various challenges, including addictions like Mark’s, will be forced to navigate the road to recovery with minimal financial help.

Life at rehabilitation

Mark is just one of a handful of Paly students who have spent time at some form of wilderness rehab.

Eliot had been acting defiantly towards his parents, exhibiting manipulative behavior on top of recreational marijuana use. The situation became so extreme that his parents searched for outside help. He was sound asleep when two bulky strangers appeared in his room, telling him that they were going take him somewhere.

“It was shocking,” Eliot says. “I had no idea what was going to happen. I didn’t really know what to think at that moment. It definitely was a little bit scary… Waking up to two people in your room taking you somewhere.”

Being taken from your house with parental consent is colloquially called, as described by Mark and Eliot, “being gooned.” Mark says these “goons” or “mountain men” are usually ex-military or ex-police force; they aren’t allowed to carry guns, but they often bring handcuffs with them to escort teens to their future rehabilitation center, whether it be boarding school or wilderness camp.

In contrast to Mark and Eliot, former Paly student, John, chose to go to wilderness therapy out of his own volition. At the end of his junior year, John was overwhelmed by the presence of drugs and alcohol in his life, so he opted to escape Paly’s drug culture. John decided to attend New Summit Academy in Costa Rica, where he is currently enrolled.

“It’s just in a different location, and it’s totally new,” John says. “I’m only able to visit [home] once every three months, and I’m gone for a full 12 months.”

New Summit blends therapy and boarding school to create a program that doubles as rehabilitation and curriculum-based education. As such, John spends a majority of his time in the classroom, but ventures off campus once a month on trips trekking through the jungle and kayaking along the gulf.

At Elements Wilderness Program, similar expeditions, like daily hikes and rock climbing, were incorporated into Mark’s regimented schedules, in addition to adult and group-led therapy sessions.

When he first arrived at wilderness therapy, Mark was stripped of his possessions and received clothing, a backpack and a sleeping bag in return. His daily routine transformed into one starkly different to that of people living in urban civilization.

The Price to Pay

The life-altering experiences described by Mark, Eliot and John don’t come without a price. According to Rochelle Bochner, founder of The Sky’s the Limit Fund, a non-profit organization that provides scholarships for these programs, wilderness therapy is typically very costly. As reported by rehabcenter.net, one usually needs a private health insurance plan to cover the expenses of wilderness therapy, usually an average of 30 days before expenses must come out-of-pocket from the participant’s family.

“Wilderness therapy can be as much as $400 to $500 a day, depending on the program,” Bochner says. “And the average length of stay is from eight to 12 weeks, so it’s like staying at the Ritz Carleton without all the plush amenities.”

With the current administration’s talk of cutting parts of the Affordable Care Act, the ability for families to afford sending their children to wilderness programs is threatened. Bochner herself is unsure about how people will continue to pay for the wilderness camps she believes are essential for recovery for numerous teens across the country.

While it’s logical for these programs to impose large tuitions, many families simply do not have the means to cover these expenses. In such cases, programs like the Sky’s the Limit Fund provide a grant to prospective participants, and wilderness therapy programs match that grant with an equal reduction in tuition. Yet even with aid, families are forced to make sacrifices to compensate for the lack of help from insurance companies.

“We [the Sky’s the Limit] have had families who have mortgaged their homes, sold their cars,” Bochner says. “We had one dad who didn’t have a car and he was getting himself to and from work on his bike and he sold his bike just to get some extra cash to help supplement his daughter going to treatment.”

As for those who can’t afford at all to go to wilderness therapy, they miss the opportunity to get valuable help. Mark reflects on what could’ve happened if he hadn’t been able to go to rehab or wilderness therapy.

“I would honestly probably either be in jail or a failure,” Mark says. “I would’ve dropped out of school — I would’ve had to choose a completely different path for my life which would’ve been a lot harder than what it [his life] is now.”

Destigmatizing detoxification

According to the Journal of American Medical Association, 50 percent of people with a severe mental condition also suffer from a substance abuse problem. While Mark and John said they did not suffer from any severe mental conditions, there is still a conceivable connection between mental health and addiction — and according to Bochner, treating kids’ mental conditions is just as important as treating their addictions.

Though Bochner says mental wellness is increasingly emphasized, the connection between wilderness camp and mental health still isn’t apparent to everyone. As a result, students like John felt apprehensive about how their peers would view them if they attend wilderness therapy.

“At first I kind of felt ashamed to be going,” John says. “I felt like, ‘Oh, this isn’t normal. But it’s nothing to really be ashamed about. It’s something I’ll look back on for the rest of my life as some of my best years.”

In contrast, Eliot reflects how he didn’t experience the stigma surrounding wilderness therapy. Instead of feeling ashamed or embarrassed, Eliot has turned to advocacy.

“I don’t think it’s a thing to be embarrassed about, necessarily,” Eliot says. “It is what you make of it. I’m pretty open about talking about it, because it made me a better person and I like being a good person.”

Instead of viewing wilderness therapy negatively, communities should learn to see wilderness programs as a needed therapeutic process, according to Bochner.

“We need to get them out of their environments,” Bochner says. “And that’s why wilderness therapy has been so successful. It takes kids out of their environment, it enables them to identify what they’re doing, why they’re going and what changes they need to be made … They have ‘aha moments.’”

Though their experiences differ, Mark, Eliot and John say that the various programs and their serene environment allowed for introspection and deep examination of what led them to wilderness camp in the first place.

“I grew a lot smarter; I try not to not do the stupid things that got me sent away,” Mark says. “I got a lot of self-awareness and self-discovery with all my past issues. It helped me gain a lot of insight on how to prevent future situations.”