It’s a cold Friday night in April, and Tony, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, stands on a brightly lit street corner in Redwood City, talking with his friends. Another kid approaches the group aggressively and attempts to instigate a conflict. As tensions escalate, Tony recalls, bystanders alert the police, who come and arrest the instigator despite no blows having been exchanged.

It’s a cold Friday night in April, and Tony, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, stands on a brightly lit street corner in Redwood City, talking with his friends. Another kid approaches the group aggressively and attempts to instigate a conflict. As tensions escalate, Tony recalls, bystanders alert the police, who come and arrest the instigator despite no blows having been exchanged.

As the police arrest two other teens, Tony, a Palo Alto High School student, pulls out his phone and begins recording the scene. Soon, one of the police officers approaches him.

“Please cross the street,” the officer says, his voice clear in a video recording of the incident shared with Verde.

“I’m pretty sure I have the right to record you,” Tony replies.

“Please cross the street,” repeats the officer.

“This is America.”

Immediately, the officer replies, “Put your hands behind your back.”

The screen goes black. Tony recalls what happened next.

Suddenly, three police officers grab hold of Tony, handcuff him and begin reading him his rights. They threaten to “drop” him if he continues resisting arrest, scratch him with the handcuffs and throw him into a painful armlock. The officers carry out the threat of “dropping” another boy, throwing him to the ground and pinning his legs up against his back. When the police eventually release the boys, they confiscate Tony’s cell phone for two months to use as evidence.

The group of kids who were arrested consisted entirely of Latino and Tongan teens, a fact that Tony does not overlook.

“Police specifically target a certain group of people because of their skin tone or their race,” Tony says. “And I feel that’s what happened to me.”

While Tony states that he was arrested for resisting, he also denies the accusation, saying he believes he experienced an excessive use of force in relation to his actions.

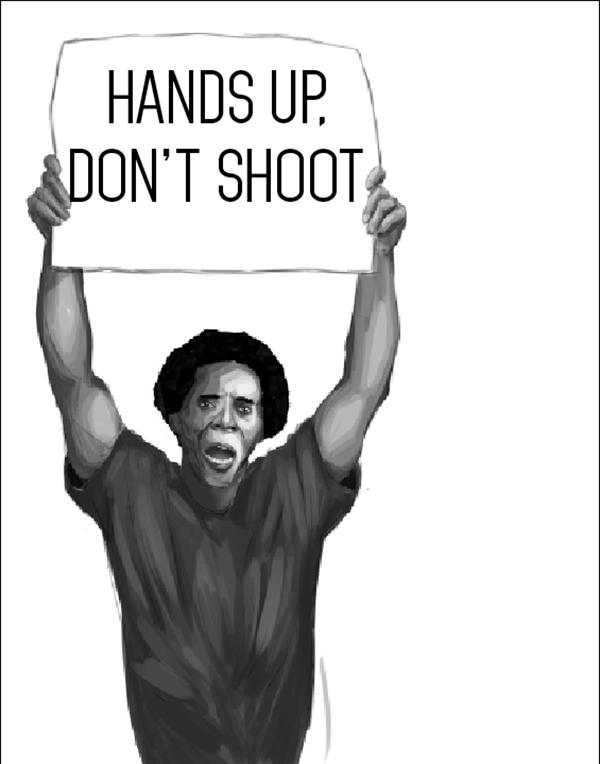

“How can I resist when my hands are up?” Tony says.

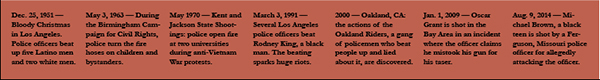

This is the type of question that thousands of people across America have been asking for decades in response to police aggression. More recently, “Hands up, don’t shoot” has become a nationwide cry for equality following the shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teen, by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

“What happened in Ferguson is a national trend,” says Garret Duncan, associate professor of African and African-American Studies at Washington University. “Every day … video clips [appear] of people, mostly black folks, and if they’re not black, poor white folks or Chicano or Latino, just getting beat down by police. Police brutality is not a new thing. It is as American as apple pie.”

Media attention nationwide has been focused on the issue of police use of force and brutality, particularly against minorities and those of color. Although Ferguson brought this issue to light, there exists a long standing national problem of relations between races and the police force. There have been several similar instances in the Bay Area, such as when police shot an unarmed black 19-year-old in San Francisco this summer and when Palo Alto police officers broke the arm of a Los Altos resident Tyler Harney in 2013. According to the Center for Disease Control from 2003 to 2009 across the United States, black suspects are two times more likely to be killed by police than white suspects.

“I think police these days could charge you with whatever,” Tony says. “They could just lie. That’s why I thought it was a good idea to pull out my phone and record the incident, because in my eyes, I knew that kid wasn’t doing anything wrong.”

Jeffrey McCune, a Washington University professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies, says that the police culture of our current times enables the sort of interaction that Tony experienced.

“I find it very dangerous that we now live in a moment where the law so easily stands on the side of the police,” McCune says. “Knowing that the trend across the country for police to enact brutalities against certain bodies in some very egregious ways.”

Ashley, an African-American Paly student whose name has been changed to protect her identity, remembers an incident in which the police accosted her dad in a way she believed was racially motivated.

“My dad got pulled over … and the police officer was like, ‘Where are you going and where did you come from.’ They said they were looking for a black guy in a Range Rover who committed a crime,’” Ashley says. “My dad got really, really upset … and kept on talking lo udly. I saw the officer do the reach-back thing … and I started panicking.”

udly. I saw the officer do the reach-back thing … and I started panicking.”

Although Ashley’s experience did not end in violence, she still feels the threat of what could have happened.

“In those types of situations, it’s not good to respond [angrily] that way, because if something were to happen … it would be like everything you have been hearing in the news,” Ashley says. “It would be that, ‘Oh my dad was acting in a certain way where the officer felt threatened and had the right to taze or shoot.’”

The use of force by police is not a singular event, but a trend relevant to the whole country, where instances of police brutality have been popping up everywhere. McCune attributes the issue to with the way police approach problems.

“It is largely problematic that we now live in a time where we have deemed police to have in some sense jurisdiction over life and death,” McCune says. “My issue is, we have moved from detain-the-subject to kill-the-criminal.”

The number of justifiable homicides by law enforcement has risen. A justifiable homicide occurs when a police officer shoots a person and the shooting is later ruled as legally justified. As reported by the FBI, the rate of justifiable homicides by law enforcement increased by 25 percent from 2000 to 2010.

Even so, there are also indications that police brutality might not be getting worse. According to Duncan, due to social media and other forms of communication, the public knows more about police brutality and is able to hold police departments accountable.

Peter Joy, a Hitchcock Professor of Law at Washington University, believes that the spread of information has led to an improvement in police policies.

“We’ve learned more about it [police brutality] over the last 10 or 15 years than we have previously,” Joy says. “I think that there’s been some improvement over the last 10 or 15 years because I think police departments are more aware, and in a lot of police departments, unfortunately not all, there have been more and more efforts to be aware of and to avoid some of the [problematic] practices.”

Use of force does not appear to be as much of an issue locally, however, as there are only about 10 uses of force per year in Palo Alto, according to Palo Alto Police Chief Dennis Burns. He adds that the department’s last taser activation was two years ago and the last officer-involved shooting occurred over 13 years ago.

“Police come into contact with a lot of people every day, and more often than not there usually is not a use of force,” Burns says. “In fact, it’s very, very rare.”

Although there have been fewer reported official uses of force, these statistics might not account for less tangible incidents, such as the ones Ashley and Tony experienced. For example, in 2008, in response to a string of robberies, former Palo Alto Police Chief Lynne Johnson issued a statement that instructed police officers to question all African-Americans they encounter because many of the suspects were black.

“When our officers are out there and they see an African-American, in a congenial way, we want them [officers] to find out who they are,” Johnson told City Council, according to ABC News.

Because many of the recent incidents of police use of force involved minorities, and the police have long been accused of racial profiling, people have brought forth the question of how race plays into police brutality. To McCune, it is the devaluation of black bodies that leads to the aggression against them.

“There is this stronghold of racism that teaches young white men and some young white women that black bodies are not valued,” McCune says. “When it comes to criminality, it’s easier to treat those bodies differently than you may treat criminal white bodies, because they’re not your own.”

While Burns acknowledges that racism remains prevalent, he feels that the PAPD’s policy of Fair and Impartial Policing can help address this issue.

“It [Fair and Impartial Policing] is acknowledging that we all have implicit biases, and to be aware of those biases but not to act on them and to treat everyone with dignity and respect,” Burns says. “The constitution applies the same to all of us.”

Two Palo Alto police officers were recently recruited by the national Department of Justice to travel to different police departments around the country and teach workshops on Fair and Impartial Policing as a response to racial profiling, Burns adds. It’s a strong indication that PAPD’s Fair and Impartial Policing is working, he says.

Joy emphasizes that minority groups say racial profiling by police is commonplace.

“I know that in a lot of poor communities, and especially in a lot of communities of color, it’s hard to find somebody who hasn’t had a story of where they believe that they have been racially profiled,” Joy says.

When individuals such as Tony have bad experiences with police, it can lead them to harbor feelings of resentment and distrust towards law enforcement.

“I told him [the police officer], ‘I wanted to be a police officer when I grew up, but since this night, and ever since I saw how you treated me, I don’t want to be a police officer anymore,’” Tony says.

This loss of trust experienced causes the effect of having a community that doesn’t want to interact with police. A Vera Institute of Justice study in 2013 found that policies such as New York City’s Stop and Frisk, in which police officers detained suspicious looking people and searched them, led to decreased willingness of the community to report crimes. For every time that a person was stopped, the likelihood that they would report a crime decreased by eight percent.

According to East Palo Alto resident Tony, people in EPA, a community largely consisting of minorities, don’t see the police as helpful and instead avoid them, fearing violence.

“I feel like if there’s a problem, something going down, it’d be safe not to call the police because you don’t know what could happen,” Tony says.

A Paly junior who wishes to remain anonymous feels that police actions against minorities can be justified.

“If you see a black person with saggy pants walking around suspiciously, any type of authority might get suspicious,” she says. “I don’t think it’s good that police can make generalizations like that, but I do think that in the past, the people who got caught were the sketchy looking people.”

The most recent studies show that the majority of crimes are committed by white people, although the majority of people sent to jail are minorities. The FBI reported in 2012 that 69 percent of people that are arrested are white and only 28 percent are black, but 58 percent of the prison population is black or Latino. White people make up 35 percent of the prison population.

“In terms of the police, we need more training, more community interaction,” McCune says. “We need a community outreach system, rather than a community regulation system. We need more community activities with the police where we’re engaged in collaboration rather than antagonism.”

Echoing McCune, Burns says the PAPD needs to be a resource for the community, not just to enforce law but to educate and collaborate with others when there is a community problem. He also acknowledges that the police force should be taught to appreciate the diversity in its community.

“I want people who appreciate difference and understand difference — but know that difference is not deficient, that difference does not mean that you should be made suspect,” McCune says.

Burns says police and citizens need to act now in order to prevent the vicious cycle of racial profiling and police brutality from continuing.

“This is not a theoretical issue,” Burns says. “This is very real for people. We need to know each other better and have community dialogue and engagement.”

To Duncan, professor at WUSTL, understanding the interrelatedness of all people is the first step towards solving these very real issues.

“I would like to see people understanding their relationships to people they did not know they were related to before,” Duncan says. “Across race, across class, across nationalities, I would like to see people knowing that we’re all related; we’re all part of the fabric called humanity.”