The first homework assignment I received in my American Literature class was straightforward: “Create a visual representation of the American dream.”

What is the American dream?

The five words, seemingly insignificant, small and isolated on the vast expanse of white, glared up at me. I grabbed some pens and began absentmindedly scribbling words.

I was growing increasingly frustrated; the sheet of white paper in front of me had become a chaotic battleground of pens. Sketches scarred the fiber and a massacre of red, blue, and black ink depicted the mess of emotions that brewed within my mind. I scrawled the only answer I could think of onto a blank corner of the paper: It depends on who you are.

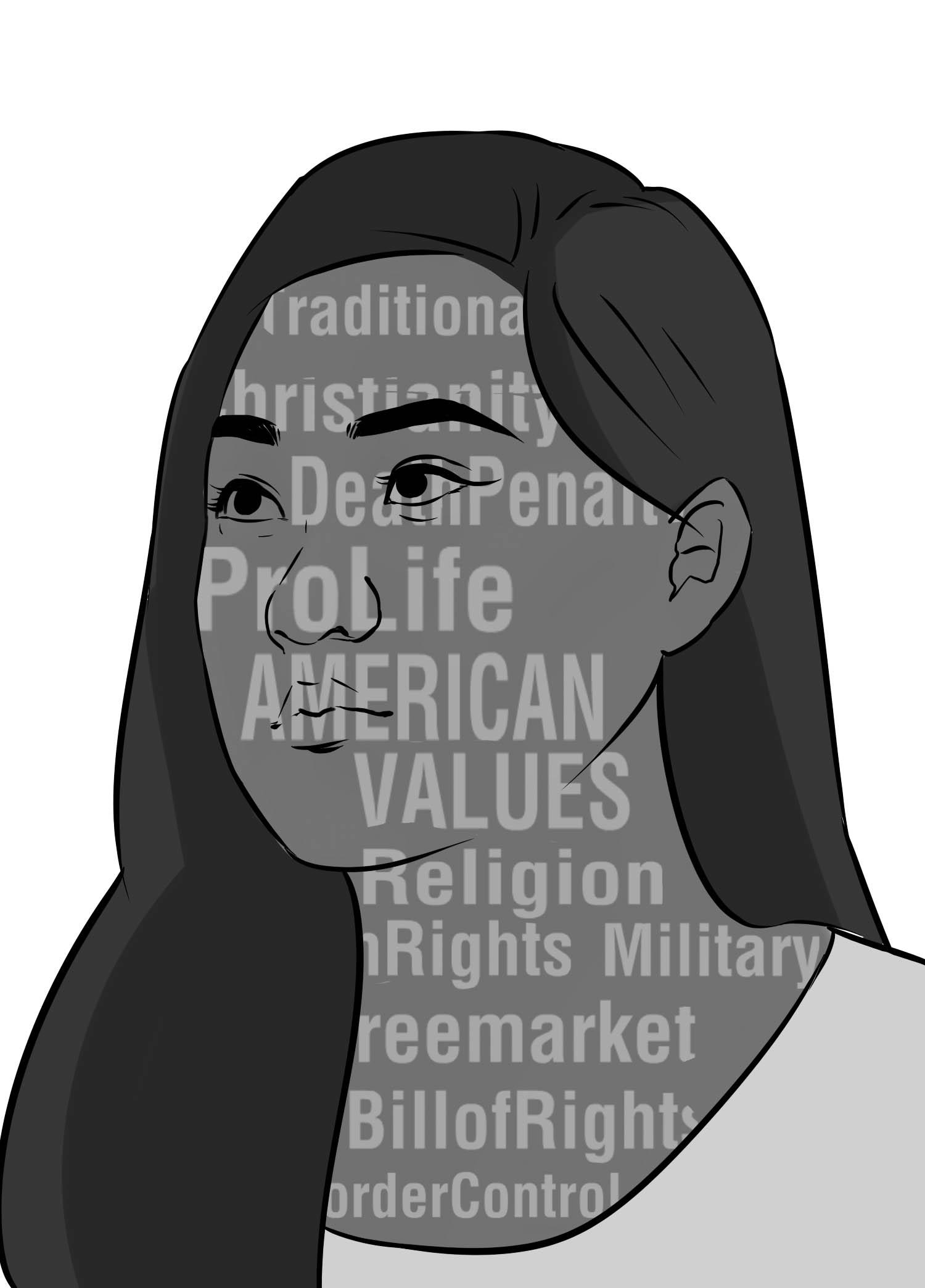

The assignment was no longer just an artistic interpretation of the American dream. It became a hunt for who I am, what I believe in, and what the significance of the American dream is to me. I began trying to untangle myself from the knot of emotions, biases, and conflicting ideas — the result of 16 years of growing up as a conservative in liberal Palo Alto.

It became a hunt for who I am, what I believe in, and what the significance of the American dream is to me.

I ask myself why I am so different from everyone else around me. How were our upbringings different, and what caused me to feel this way? Surely it couldn’t just be the immigrant experience; many of my peers are children of immigrants or are immigrants themselves.

My parents’ conservative values were passed down from their parents but they, too, were immigrants. I didn’t understand how conservatism within my family survived liberal Manhattan and even more liberal Palo Alto. But tracing my family history was a place to start.

My paternal grandmother started looking toward America when Mao rose to power. She and my grandfather fled to Taiwan in 1966, right before the Cultural Revolution. In Taiwan, she continued dreaming of a place of opportunity for her children to grow without fear of the government. She dreamt of a place where her children would never go hungry and a haven where they could grow as intellectual thinkers and good people.

Meanwhile, my grandfather came to America from Taiwan to get his law degree, leaving my grandmother to raise two young kids on her own. Three years later, they reunited in New York, living in a small apartment in a racially divided neighborhood. Despite the hardships, she never ceased to tell her children to be grateful for what they had, no matter how hard times were.

Despite the hardships, she never ceased to tell her children to be grateful for what they had, no matter how hard times were.

The lesson was something that my father had always kept in mind as he grew older. His father had come back to Manhattan and went straight into the workforce. He had a burning ambition to make the American dream become a reality for his family. Consequently, he began his own business semiconductor manufacturing. This was a business my father would take over two decades later.

Although my father didn’t see my grandfather often due to his demanding work schedule, my grandfather’s success taught him that hard work always pays off. This belief is also the reason why my father supports a free market; government interference could disrupt a hard-working citizen’s efforts.

Later, this became one of my strongest beliefs: To always give people the amount of credit they’ve earned.

My parents taught me that American dream today means going to a good college to work in a STEM related field so my future family and I can live comfortably. This doesn’t differ from everyone else’s dream — at least not in Palo Alto. My definition of the American dream doesn’t make me conservative the way it had influenced my parents and grandparents’ beliefs — it was the traditional values my parents raised me with as a means to achieving that dream.

This also became the foundation of some of my political beliefs. For example, I support the death penalty because I believe that if someone can take another person’s life, it is only just that they give what they take. Additionally, I support gun rights and I have a conservative stance on foreign policy. However, I don’t consider myself to be “very Republican” on the entire spectrum of social issues; I am conflicted on abortion, legalizing marijuana and immigration, and I’m more liberal about LGBT rights.

My peers and the environment have clearly begun to reshape my conservative views. Part of the influence was ideological; having clearly seen both sides of the issue, there was no right or wrong answer for me anymore. Part of the influence was social, too; I had heard the way my friends and the general public speak about conservatives, and I began to alienate myself from my ideals for the sake of social acceptance. The line between what I had considered as morally good and what my peers had considered as morally good became blurred; I tried so hard to blend in with everyone else. I no longer felt confident in what I believed in and strongly envied those who could feel so passionately about issues. I was engulfed in the stigma that surrounds conservatives.

Part of the influence was ideological; having clearly seen both sides of the issue, there was no right or wrong answer for me anymore.

I won’t forget the little things that gave away the general negative feelings towards right wingers: How disappointed one of my friends looked when I told him I was right-leaning, or how some people would give looks whenever I tried to state my ideas. I won’t forget the tone of unacceptance embedded in one of my teacher’s voice when they found out I was conservative.

It didn’t help destigmatize conservatives when President Trump broke major headlines during the whole election campaign. A brazen and blunt man, Trump’s ideas are amplified and distorted by his New York attitude and crude comments. While many feel Trump is a fear-mongering demagogue, I don’t think Trump is as bad as everyone makes him out to be. But seeing how divided America is, I have concerns over how we can keep the “united” in United States of America during the next four years.

I admit that I’ve spent quite a bit of time crying, tired of feeling like I had to stand alone all the time, frustrated at myself for being raised conservative in the first place. I was jealous at how my friends could speak freely about their opinions without needing to understand what it would be like to be me.

I’ve told myself over and over that I have the same rights as everyone else to speak my mind. I supposed Verde is one part of the lesson I learned about it. Back when I joined in sophomore year, I was terrified of everyone. Verde was chock full of intelligent thinkers and brilliant writers who looked left while I bit my nails too often and spoke too soft and stood too far to the right. No matter how many times I told myself I had no right to censor myself, I was still scared.

Verde was chock full of intelligent thinkers and brilliant writers who looked left while I bit my nails too often and spoke too soft and stood too far to the right.

But after a while, speaking up slowly became easier. All my fears came from the fact that I was going to be judged and disliked by others, but mostly, I am the only one judging myself. I still get angry words and unfriendly glances, but something tells me that I sometimes earned those looks because I was able to say something that caused someone to think.

When the project was due, I turned in a pencil drawing of an immigrant dreaming. I knew that there was no way I could spin all my revelations into one simple drawing, but that was okay. I am beginning to figure out who I am — which I know is going to be quite a journey — but I have a bit of a feeling of what it’ll be like when I get there. And for now, that is enough.