Among file numbers, government officials’ signatures and barcodes in a hundred-page document is the word “confidential,” redacted in what seems like the rushed strokes of a black pen. Printed in the document are several mentions of Palo Alto High School, Cubberley High School and the addresses of local churches and organizations.

In the 1960s and 1970s, when student protests and underground newspapers were commonplace in Palo Alto, the FBI sent spies to the city to monitor and report on student activity and generate reports about student organizations pushing for social, economic and political reform.

“The basis was that high school students were being led by adults who had some ulterior motive.”

— Aaron Fountain, JR, archivist

Story continues below advertisement

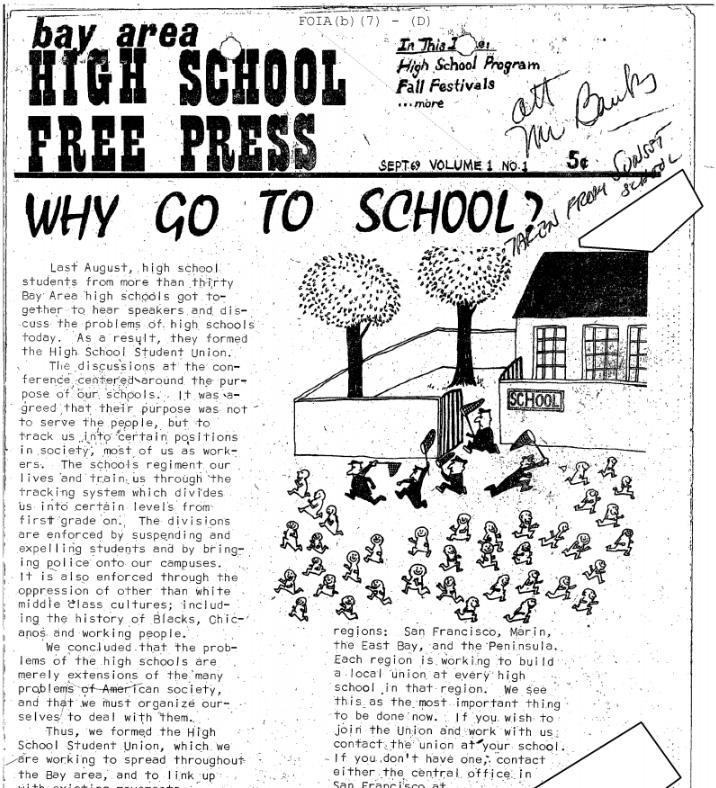

The files describe the progression of the student-led organizations Bay Area High School Student Union, Radical Student Union and United Student Union in thorough notes released by the FBI. Investigations started in 2014 after Aaron Fountain, Jr., a former history Ph.D. candidate at Indiana University, Bloomington filed 450 Freedom of Information Act requests.

He filed the requests while researching for his graduate thesis on student protests in the 1960s and 1970s in the Bay Area, then sent them to librarian Rachel Kellerman, who forwarded the files to Verde Magazine.

“I’m just trying to show that the high school student movement was indeed a social movement that had its own goals, strategies and ideology,” Fountain says.

From underground newspapers produced by students to anti-war student discussion groups, the “sheer radicalism” and “political sophistication” of the movements, as Fountain puts it, were what drew the FBI to this small, upper middle-class community in California.

At the time, the FBI was under the conservative-leaning leadership of the Hoover administration, diligent about monitoring high school students’ activities. It maintained alphabetized lists of radical students, monitored phone calls and kept tabs on the progression of radical youth organizations.

“The basis [for the investigations] was the idea that high school students were being led by adults who had some ulterior motive,” Fountain says. “So pretty much the idea that they were being pawns.”

Nowadays, however, it is evident that students are the ones initiating social movements and protests.

The recent March 28 student-led “March for Our Lives” demonstration in Washington, D.C., along with smaller protests in the Bay Area, pushed for tighter gun control and highlighted the power of students. Students across the country also gathered in locations such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, armed with posters and their voices.

“Students are addressing the issue of such students rising to power, the right to free speech, the right to due process and the right for students not to be kicked out of school, which was something that was quite common in the ‘60s and early ‘70s,” Fountain says.