As fresh morning fog seeps into the dark soil of his Watsonville farm, Robert Kitayama weaves his way around flower-filled delivery trucks and heads towards dozens of massive greenhouses holding seedlings, buds and blooming flowers. These enclosed acres of colorful flowers, ranging from snapdragons to lilies, mark years of familial hard work, dating back as far as World War II. Warm, humid air cascades outwards as Robert pulls the greenhouse doors aside.

“After WWII, my grandpa and his brothers didn’t have any work because they were in internment camps because we’re Japanese,” says Grace Kitayama, Palo Alto High School junior and daughter of Robert Kitayama. “They mostly didn’t have college educations, so they worked for a flower grower and then they started their own farm selling carnations.”

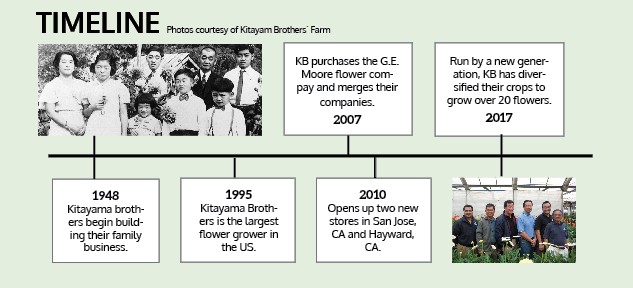

Founded in 1948 by Grace’s grandfather and three great uncles, the farm approaches its 70th anniversary. Through the 70 years of it’s existence, the Kitayama farm has grown and expanded in ways the original Kitayama brothers had never imagined. Personal ambitions would lead the Kitayama brothers to start their own flower growing business with the help of borrowed money and land. The risk that they took would prove to bring great rewards, as their farm began to grow and prosper.

“They [Kitayama Brothers] had 50 acres in Union city before it was a city,” Robert says. “They put up greenhouses and by the mid-60s. They were the biggest carnation growers in the west.”

Along with having a substantial presence in the city’s agricultural areas, the Kitayamas have had a strong political impact as well. Robert’s cousin, Tom Kitayama, made history as part of a group that created the developing community in Union City.

“Union City wasn’t a town then, and my uncle Tom was part of a group that created the community there,” Robert says. “He became the mayor of Union City, and he was the first Asian American mayor in the United States.”

Following the demand for carnations, Kitayama’s father Ray and his uncle Kee decided to expand the family farm to Colorado and Watsonville.

“In 1966, my father, Ray, decided to move to Colorado,” Robert says. “At that time, Colorado grew 20 percent of all carnations in the US, so I grew up in Colorado.”

“In the late 60s, my uncle, Kee, moved to Watsonville, and he started growing the location that I now manage. By the 70s, we were growing in Union City, Colorado and Watsonville.”

Passing the business down

Originally, Robert did not plan to enter the family business. “I was going to do anything but farming because it’s really hard work,” he says. “And as a kid, to work in the greenhouse, it’s hot and dirty and long hours. So I said I would do anything but that.”

However, he still felt compelled to help run the family business, particularly in the farm’s sales aspect. As president, Robert’s typical work includes meetings and phone calls, just like a lot of other working Silicon Valley employees. “It’s probably not that much different,” he says. “I mean it’s a farm, it’s like business. You spend a lot of time planning or evaluating.”

Although he doesn’t grow flowers himself, Robert loves the flower industry and its uniqueness.

“We grow a product that I think is unique and gives people a lot of pleasure,” he says. “There aren’t many flower growers around, and it’s very challenging. Our family’s been growing flowers for almost 80 years, [so] it’s like carrying on a big family tradition.”

After years of farming, his generation is now the one that runs the expanding family farm.

“Now, it’s actually me and I have two brothers and a cousin who work in the business so it’s still a family,” Robert says.

The farm today

“Twenty years ago in Watsonville, I’m guessing, there were around 60 flower farms, now there are around 10,” Robert says.

The cause of this can be traced back to flower imports from South America. Originally specializing in roses, a popular import from Southern American countries, the Kitayama Brothers’ had to change up their focus crop.

“We had to get out of roses,” Robert says. “Now most of the roses come from Colombia and Ecuador, so we are now growing mainly lilies, gerbera daisies, snapdragons, liz hamptons, gardenias, calla lilies. Those are our main crops.”

Despite competition from foreign flower imports, the Kitayama farm has found great success in local markets.

“I think we’re the biggest flower farm near SF, so we like to promote locals,” Kitayama says. “We sell more than 50 percent into the San Francisco area, and then we grow right on Monterey bay.”

Being a farmer in Silicon Valley

“I love it. It’s unique,” Robert says. “We live in Palo Alto and Menlo Park and nobody’s a farmer. Everyone is a software engineer.”

To him, the distinctive nature of the agricultural industry makes it all the more enjoyable.

“In California, agriculture is probably [ranked] one or two as far as industries, and everybody needs to eat so it’s very interesting that you can’t find a farmer in your area,” Robert says. “Again, I’m not out there in the ground, digging the soil, but I am very fortunate to be able to do this. It’s hard work.”

Grace says that there are both benefits and disadvantages to being part of a farm-owning family.

“I don’t get to see my dad as much because he works so far away, so that’s not great,” Grace says. “But other than that, I honestly think that it’s brought me and my extended family closer, which has helped. [And] we always get a lot of free, fresh flowers, which is fun.”

Future of the farm

In recent years, weather and a lack of labor have been the biggest challenges to owning a farm. However, Robert is optimistic about the future of the farm.

“I feel that as long as the water stays in good quality that what we do will still be in demand,” Robert says. “There’s less and less production, there’s not many greenhouses around, and I think things like local and proximity of market will still be important as long as we’re growing things that people want, that are in demand.”

“Who I can convince to keep doing this, that’s another question,” Robert laughs. “I don’t think Grace and [her cousins] are very interested, to be honest. But this is the kind of business that you really have to love. So, If I have to hire outsiders to run the business, I will, because it’s more important that someone who works will do a good job rather than having the same name.”

Grace, her sister and her cousins have helped out on the farm occasionally over the summer. “I don’t know how to grow a flower, but I know how to box it, grade it (tell if it’s good or not) and ship it, which is important too,” she says.

However, Grace doesn’t see herself working on the farm. “My generation — me and my cousins — we’re not really that interested in the family business, and my dad is trying to get us interested, but none of us are,” she says.

In Robert’s eyes, flower farming is a profession that requires great care and love.

“It’s a great profession, but, sometimes people romanticize it,” Robert says. “Everyone wants to be organic and run a nice little organic farm, but… I mean only do it if you love it because it’s going to be what you’re doing seven days a week.”

He references the passion that his father, one of original founders of the Kitayama Brothers farm, had for growing.

“My father loved growing flowers and he was like ‘Oh goody, I get to do what I love everyday,’” Robert says. “So that’s what you need.”