“THIS IS A PEANUT FREE ZONE!” We all remember the designated lunch tables in elementary school that separated peanut free tables and tables where you could have all the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches your heart desired.

You may have disregarded this rule, but some Palo Alto High School students cannot afford to be so flippant.

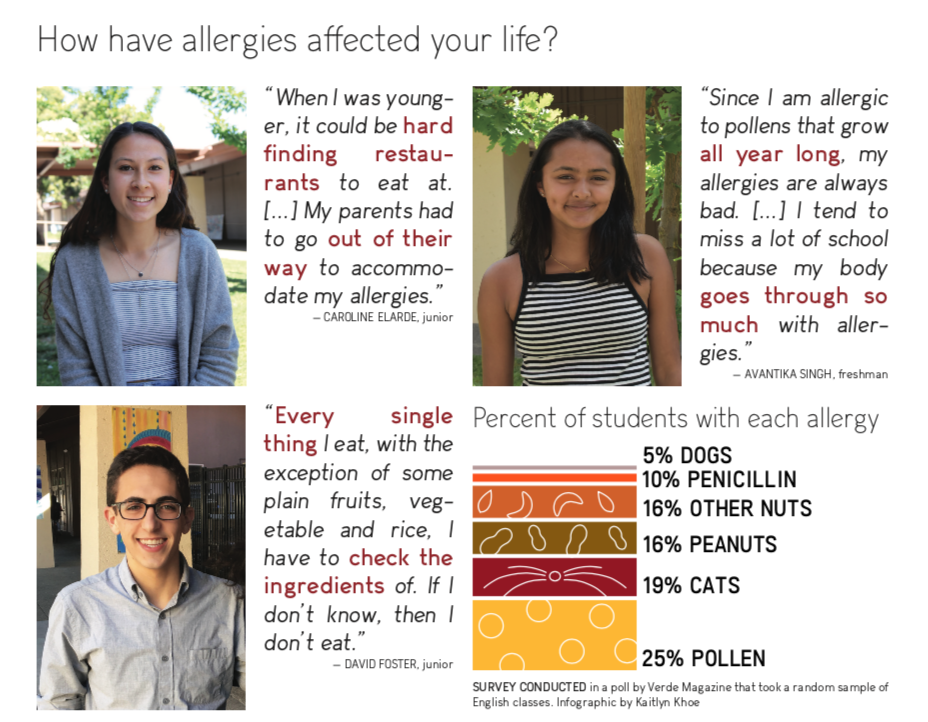

“It [having allergies] has a gigantic impact on my life,” junior David Foster says. “Every single thing I eat, with the exception of some plain fruits and vegetables and rice, I have to check the ingredients of.”

Similarly, Paly junior Megan Bitler recalls that as a child, she would stand outside the kitchen blocked by a baby gate then be carried to a high chair for meals in order to prevent her from reacting to allergens she could have come in contact with on the floor.

“We kept her environment with food very limited so that we cut down on the risk of having possible reactions,” says Julie Bitler, mother of Megan.

While reading food labels and steering clear of restaurants becomes the norm for some allergy sufferers, others seek further protection from experiencing serious reactions by taking part in allergen trials.

“They [allergen trials] are a wealth of knowledge and typically a reminder that treatment is possible and they can achieve their goals,” says Whitney Block, nurse practitioner at the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford University.

The younger Bitler and family decided that doing a Phase I clinical trial would benefit her, especially since as she grew older, she may not have the same protection from allergens in high school and college as she did in elementary school.

“I started it [an allergy trial] when I was about 11,” Megan Bitler says. “My mom had been trying lots of years to get me into a trial from talks to sign up sheets and waitlists.”

For the allergy trial, patients first undergo allergen testing to determine their sensitivity to different foods.

“What we [the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma and Allergy Research at Stanford University] do with oral immunotherapy is introduce the allergenic food in very low amounts and gradually build-up over time to retrain the immune system to not have reactions,” Block says.

At Bitler’s first appointment, she was exposed to this type of allergy treatment.

“My first appointment I had, they [doctors] had me do a double blind where they give you apple sauce and mix in a powder — you don’t know what it is ,” she says. “It could be peanut, egg, milk or soy or it could be a placebo.”

After reacting to milk, soy, egg and peanut allergens, doctors gave Bitler several powders that contained the proteins of reaction-inducing foods for her to take home and consume over the next two weeks. Slowly, with the help of Xolair (a medication that reduces and slows reactions), her immune system learned to tolerate allergens.

“Without Xolair I would probably not have done the trial in the time that I did,” she says. “I would probably still be in the trial now because my allergies were so bad.”

Slowly, Bitler’s dosage increased until she was able to eat the actual foods she had once reacted to. Now, she eats eight peanuts, two thirds of an egg and a gram of soy milk and a gram of milk every day.

Since her trial, she continues to send emails to other students living with severe allergies, describing her story and the impact it makes in her life.

“It [the allergy trial] has given me a feeling of safety and the ability to venture out,” Bitler says. “For example, I am able to travel to more places and not worry about nuts on the plane or what I’m going to eat once I’m there. I don’t have to worry about cross- contamination.”

Often, individuals are skeptical about a food that has the potential to kill them, but the desensitization provides protection to allergens in the future, according to Bitler.

“It makes things like approaching college much easier because I don’t have to think so much about being so far away from home with my allergies [and how it may] affect my college experience,” Bitler says.

Like Megan Bitler, many students seek allergen trials to have more freedom in college and later in life, and people like Block make an effort to support their patients.

“Everyone is different in what their goals are,” Block says. “Some people want to be safe around cross-contamination while others want to eat whatever they want (including their allergens) without worry.”

Block is currently working with her colleagues around the country in order to open clinics nationwide.

“I’m learning that setting up the business side of the clinics can take a long time from a legal and regulatory perspective, but other than that things are going quite smoothly,” Block says.

With the possibility of increasing access to potential food allergy treatments, more individuals will be able to manage their life-threatening allergies.

“It [allergy trials] gives people with allergies the opportunity to desensitize themselves to their allergies and allow for a safer life,” Megan Bitler says.