Senior Miguel Moreno describes his worst night of sleep ever. Once in his first semester of junior year, he went to bed at 5:45 a.m. only to wake up at 6:30 a.m.

“One night, I had to prepare for a communications speech, finish a chem lab, finish Analysis [Honors] homework, and look over my Japanese notes for a test,” Moreno says, “But every time I sleep less than three hours, I always get a fever by the end of the day.”

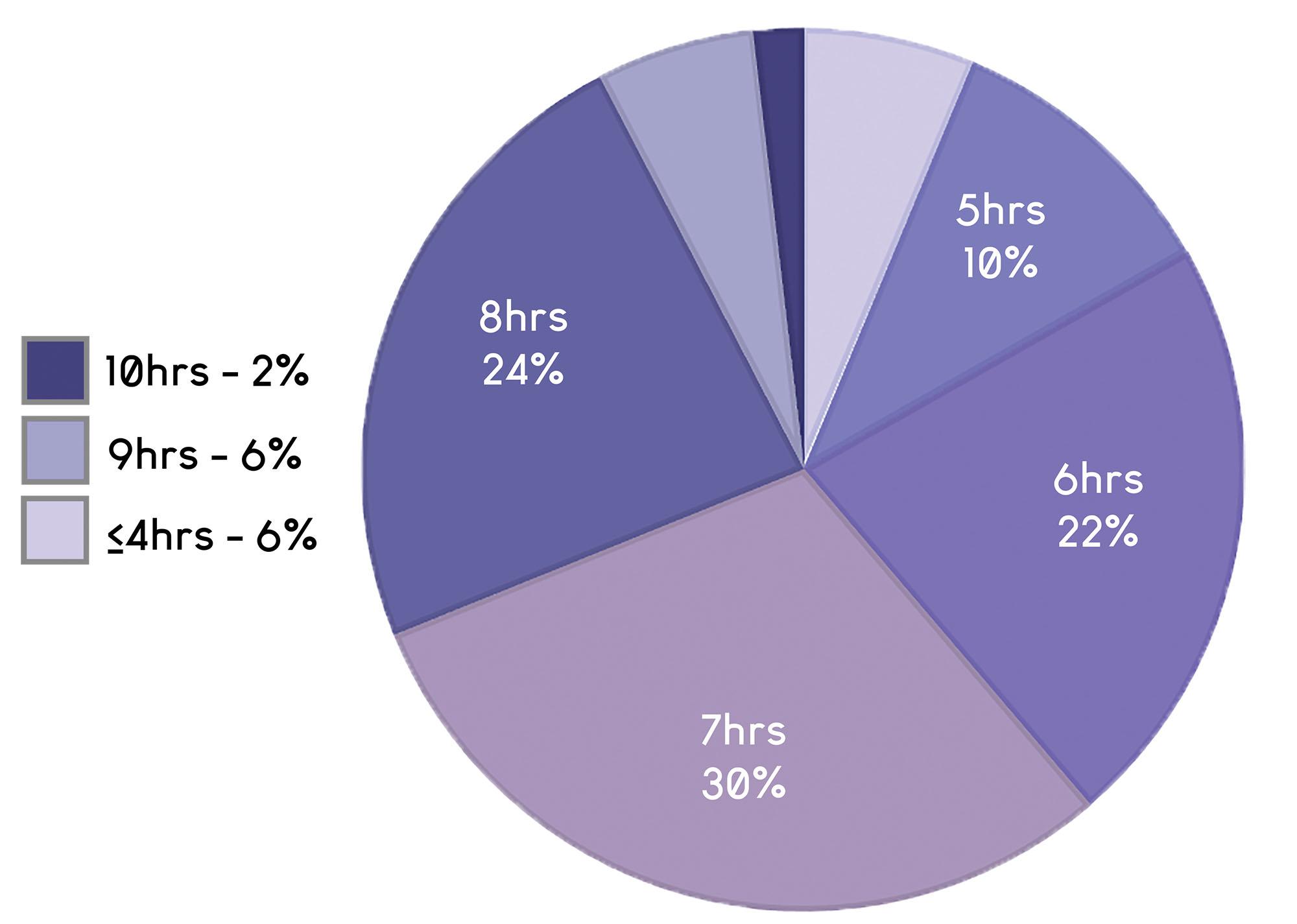

Moreno is in good company. According to the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey conducted by the Center for Disease Control, only 27.3 percent of high school students get more than 8 hours of sleep on an average school night.

A proposed bill, which failed late last year in the California legislature, would have required all California middle and high schools to start at 8:30 a.m. at earliest. Currently, Gunn High School starts the day at 8:30 a.m., and Palo Alto High School’s Innovative Schedule Committee is considering the possibility of a later start time next year.

All of these efforts are meant to combat sleep deprivation, which decades of research has shown to have negative health consequences.

Health Effects

According to Jamie Zeitzer, an associate professor at Stanford University’s Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine, there are two kinds of sleep deprivation: acute and chronic. Acute sleep deprivation is a short term sleep loss, like pulling an “all-nighter.” Chronic sleep deprivation is the lost of sleep over period of months or even years.

“There’s no hard-and-fast rule, but basically if you’re not getting the amount of sleep you need to perform optimally, you’re sleep deprived,” says Christopher Farina, an AP Psychology teacher at Paly.

According to Farina, sleep debt is a term used to describe cumulative sleep deprivation over a two-week period of time. As sleep debt builds and sleepiness increases, a person’s cognition decreases along with their ability to judge the severity of their condition.

“You may notice that you’re getting pretty tired, but you don’t notice the degree of the effect,” Farina says.

Zeitzer explains that people who remain chronically awake at night for professional purposes are able to train themselves to ignore sleepiness, but would still perform just as poorly as any other person who is awake in the middle of the night.

“At a more local level, people just need to be more aware of the consequences,” says Nicholas Blonstein, a senior at Paly who gave a Tedx talk on sleep deprivation last year.

According to Kate Kaplan, a psychologist that treats sleep and anxiety disorder, there are some fairly severe effects to chronic sleep deprivation. Kaplan is also a part of the Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine.

“We have evidence that inadequate sleep in adolescence leads to poor health outcomes,” Kaplan says. “[Inadequate sleep] increases overweight and obesity, increases in poor food choices [and] other risks….We know that new episodes of depression, different anxiety disorders [and] suicide increase with sleep restrictions and deprivation–that’s true in adolescents as well as adults.”

School Start Times

Summaries on the issue of delayed school start times by the American Psychological Association and the Center of Disease Control assert that significant improvements in student’s mental, physical, and academic well-being have been proven in studies following a shift back in school start times.

“At a school like Paly where everyone is taking hard classes, it’s not hard to imagine why students aren’t getting enough sleep,” junior Annie Tsui says.

Many students find themselves skimping on sleep in order to finish homework and study for tests after coming home late due to a variety of extracurriculars. Even so, the problem impacts more than just students.

“I would say, students and staff and admin — across the board — you’d be hard pressed to find a lot of people that are getting enough sleep every single night–the amount of sleep that they individually need,” Farina says.

Tsui attributes this to the culture at Paly.

“We’ve fostered an environment where we encourage competition among students,” Tsui says.“Now this obviously has its benefits, but sometimes it really does takes a toll on students.”

Blonstein wants schools to develop reward systems which would academically and directly benefit students for sleeping more and emphasize sleep over schoolwork. He believes that if schools can shift their culture to prioritize wellness and adequate sleep, students will find themselves sleeping more due to reduced pressure.

“Even though you may not see the consequences on the person, they can be hidden monsters,” Blonstein says. “Things like anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts are all connected to sleep deprivation, and ADHD, too.”

Electronics and Sleep

Aside from the chronic sleep deprivation most teenagers experience, the overall quality of sleep has also been decreasing. This is mostly due to the introduction of backlit devices into our daily lives.

“When light hits your eyes, it stimulates the suprachiasmatic nucleus in your brain which sends signals to your pineal gland to stop secreting melatonin, a hormone that tells your body to feel sleepy,” Farina says. “If it stops secreting that hormone, you stop feeling sleepy. When you have a backlit device, it’s shining that light directly in your eyes, your body stops producing melatonin, you stay awake, and it takes you longer to fall asleep afterwards.”

Zeitzer, however, provides a more nuanced view on the effect of electronics on sleep.

“If you’re exposed to very dim light all day, it’ll [the light] be impactful, but the light itself doesn’t have a lot of impact if you’ve got normal lighting during the day time,” Zeitzer says. “What is quite impactful is what you’re doing with that light. If people are using electronics and staying up late, the electronics are either encouraging more wakefulness or causing the individual to be stressed; neither one of these are good for promoting sleep.”

According to Zeitzer, in order to improve sleep quality, every individual needs to evaluate their individual reasons on why electronics might be keeping them awake.

Conclusion

Zeitzer and Kaplan both suggested that the best way for students to improve sleep quality is keeping a consistent daily sleep schedule.

“Basically, you want to have as much consistency as possible to have as strong a circadian clock as possible. If you start messing around having different start times, presumably, that can cause different wake times. With different wake times, then you’re gonna start actually causing sleep to be more problematic,” Zeitzer says.

“If you can make little changes to try and make improvement towards that ideal, that’s something that everybody can do. You will sleep better, you will feel better and you will perform better,” Farina says. v