He peers out of the stucco house, loose-lipped and sunken-eyed. The man is rangy with tightly drawn, rusty skin and a fine shock of white hair. He passes a single slender Newport to the woman at his door, who lights it, flicking off the burning tip and releasing a puff of grey.

It is a Sunday, one of the year’s first, and Jane, who briefly attended school in the Palo Alto Unified School District, is showing me around East Palo Alto’s arms trade. Her name, like others in this story, has been changed to preserve her anonymity. Cars blur past like bullets on the highway, each leaving in its wake only a trail of exhaust and a string of drivers pursuing it northward on 101.

The man addresses Jane. “Hey honey, it’s been a while. What can I do for ya?”

“Yeah it has, huh?” Jane says. “I heard that [someone’s] got a gun around here?”

“Down the block,” the man says. “‘S for a good price, too. Got a clip and everything. You gonna buy?” The man is old enough to be her grandfather, selling single cigarettes out of his front door. His accent, like his manner, belongs in the American South, and he eyes me like an unwelcome tourist in East Palo Alto, so clearly out of place and touch.

Jane tells him she isn’t, that she was just curious. She exchanges a crumpled bill for a cigarette, and lights it.

“See? That’s how easy it is to get a gun here,” Jane says to me, once out of the man’s earshot. “All you gotta do is cross 101 to East Palo Alto … He’s cool, though, the dude who’s selling. Tons of people are strapped [carry concealed weapons] over here.”

Jane does not hesitate to recount the story of the night several years before when she was shot, an accidental casualty o one of EPA’s violent territorial conflicts. We cross in front of Home Depot, where a group of day laborers are congregated near a red Ford whistling over faintly musical radio static.

“I didn’t know what was going on,” Jane says, recalling the shooting. “I just hit the floor. I remember hearing someone call, ‘Mark a— n—!’ at us and watching the car drive away, windows all tinted.”

Jane recalls the sound of the shot hammering all other noise out of her consciousness, breaking against the inside of her ears. She dropped to the floor, but before reaching it she was hit in the knee, lying on her stomach in front of the neon signs of a fast food restaurant.

“I didn’t even know what was going on that night,” Jane says. “The guys I was with helped me get home, but we didn’t call the cops or anything. I was too scared to start sh-t. I shouldn’t have been with people [from another neighborhood]. I guess they’d had beef before, but I shouldn’t have been there.”

The Facts

Shotspotter, an online service that monitors the number of shots fired in a locale during a given time, reported an average of 13.3 gunshots daily in Nov. of 2012 and 108 single gunshot incidents and 178 multiple gunshot incidents in EPA in Jan. of the same year. In the same period, not a single shot was fire within Palo Alto city limits, although several reports of gun related crime have been filed with Palo Alto police, among them the arrest of two Paly students on Feb. 8 and 11 for bringing guns onto campus and several armed robberies in the downtown area.

Getting Organized

In Palo Alto, as in the rest of the country, the debate on gun control rose to prominence on Dec. 14, 2012, when Adam Lanza killed 20 children and six adult faculty members of Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Conn. The shooting brought gun control to the center of political debate on the national level, drawing a proposal from the White House calling for “increased background checks for all gun sales, including those by private sellers currently exempt.” Also in the proposition was a reinstatement of the 1994 ban on assault weapons that was abandoned in 2004, and other clauses that have drawn serious reactions from proponents of relaxed firearm control and the National Rifle Association.

An anti-gun group based in the Silicon Valley organized in support of Obama’s proposal at its inaugural meeting on Jan. 17. The group, which includes Palo Alto residents, plans to lobby to politicians to back Obama’s proposal. Local action in support of gun control is planned for Feb. 23 by Silicon Valley investor Robert Lee and outreach coordinator James Cook. Backed by some $50,000 in funding, an anonymous gun buyback will be hosted at Palo Alto City Hall for the tri-city area including Menlo Park, Palo Alto and East Palo Alto.

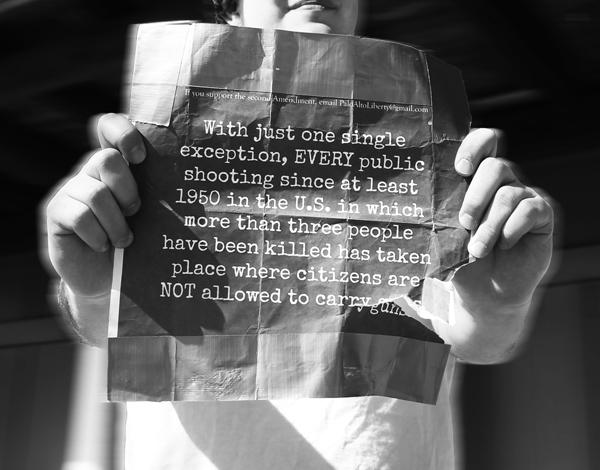

Also since the Newtown shooting, maroon signs with white text have been distributed throughout Palo Alto. The text reads, “With just one single exception, EVERY public shooting since 1950 in the U.S. in which more than three people have been killed has taken place where citizens are not allowed to carry guns.”

The signs belong to Palo Alto Liberty, a local self-described “physical manifestation” of the anarchist group Anonymous that has taken a stance against gun control. The group claims to be “fighting tyranny and corruption when and where [it] can,” and the pending gun control proposal represents a clear breach of what it considers to be an essential constitutional freedom.

The Debate

John J. Donahue III, a professor of law at Stanford University and the author of “Shooting Down the ‘More Guns, Less Crime’ Hypothesis,” argues that the relationship between gun ownership and crime is not, as argued by the NRA and much of the right wing, inversely correlated.

In EPA, gun ownership takes on a completely new shape. According to Jane, firearms in EPA are being used primarily for violent crime, an attitude that influences the mentality around firearms enterprise and culture in the city.

“I’m waking up to shootings almost every night,” Jane says. “Most of them happen cause of turf wars and drug deals.”

“We keep our beds under the window, just in case anything flies through,” Kelly, Jane’s friend, adds, warning me, as I turn to use the restroom in a nearby building, not to cross to the other side of the street alone.

The firearms that spray bullets through Jane’s and Kelly’s waking nights are sold on the street, Jane says.

“Most of the guns here are unregistered,” Kelly says. “You buy them on the street, like drugs, from someone who got it from someone else. It goes on like that, in a chain, until you get to the [original] buyer.”

“People aren’t protecting themselves at home,” Jane says, tying her scarf tighter across her forehead. “Everybody knows not to come in when somebody’s at home and start sh-t. People here have guns for the street.”

Donahue attributes the abundance of illegal weapons and frequency of gun violence in EPA to the propagation of drugs.

“EPA is a locale in which there is a certain amount of drug dealing going on,” Donahue says. “Dealers tend to need guns because they cannot rely on the police to enforce their contracts or protect them from theft because they’re engaged in a criminal enterprise. … If one thing would diminish the rate of murder and nefarious gun trade in the U.S. it would most likely be the legalization of drugs … [Palo Alto is] a growing site for drug criminality, which may well pose a problem in our future.”

A TALE OF TWO CITIES

By Donahue’s estimation, the drug trade and a host of other factors brought on by the socioeconomic divide between Palo Alto and East Palo Alto determine a split in the role of firearms in the two cities.

“In East Palo Alto, I can see people feeling the psychological need to buy guns for safety in the home, especially considering how difficult it is to [legally] register a concealed carry,” Donahue says. “In Palo Alto, that need is negligible. Guns [in Palo Alto] are used for recreational sports… and as Republican party political statements, political props of Second Amendment support.”

Lee Hughes, a Paly Junior and gun owner, has an attitude towards gun ownership that corroborates Donahue’s assumption.

“Fun!” Hughes says. “I’m not gonna lie, guns are fun. They are not evil things like everyone thinks, when used correctly. But key words are ‘used correctly,’ since they are not toys and if you think of them as such you don’t deserve [to own] one.”

To Kelly and Jane, the restriction of gun ownership surpasses the realm of individual liberty and crosses into that of individual safety. They are not concerned with the party politics surrounding gun control, and do not stop to think about the intangible implications of tighter restrictions or of laxer ones.

“If I’m not going to be waking up to gunshots, though, it means that somebody’s getting them off the streets,” Kelly says.

Jane is concerned for the quality of life and the degree of safety for herself and those around her, concerned that she’ll hit the pavement again with a bullet in her knee, afraid to get help.

“In EPA, guns are being used to kill and injure,” Jane says. “I don’t care what, but something needs to be done to stop it.”