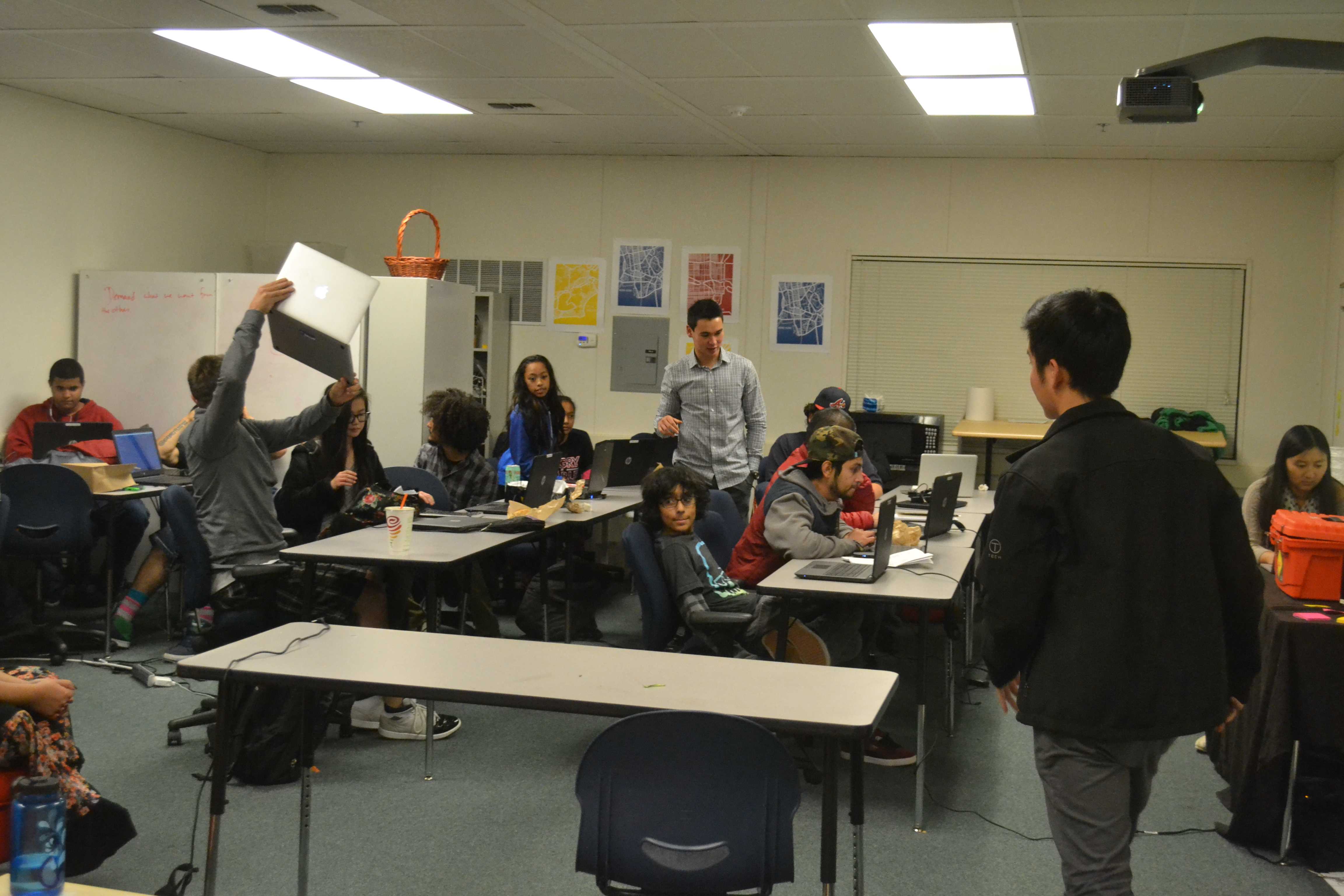

Late on a Thursday night, light and enthusiasm spill from a room where clusters of students sit with shiny laptops as Shadi Barhoumi paces the front of the room, emphatically illustrating his lecture about Javascript with various hand gestures.

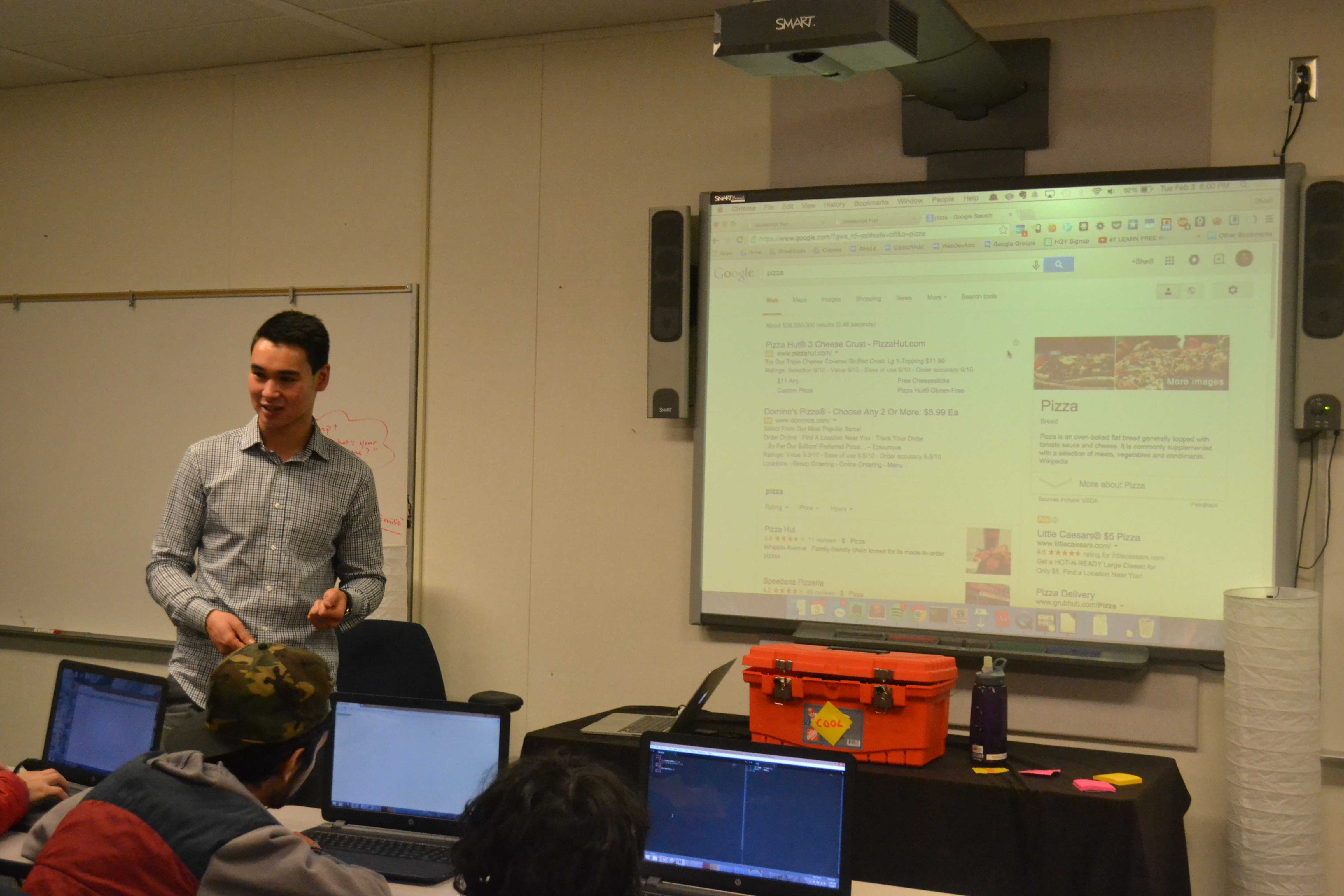

“If I search ‘nice people at Stanford,’ Javascript takes that and uses it to search a sort of local database,” Barhoumi explains to his class at Streetcode Academy, a nonprofit that seeks to bring computer programming opportunities to East Palo Alto.

He opens up a Google browser and hovers uncertainly over the search bar.

“If I search …”

“Pizza!” yells one student.

“Thanks, just blanked out,” Barhoumi replies.

Barhoumi, a Stanford sophomore who has been passionate about teaching computer science since his high school years, has worked as a coding instructor at Phoenix Academy in East Palo Alto and as a founder and instructor at Code Camp last summer.

Today, as a cofounder of StreetCode Academy, Barhoumi continues in his effort to inspire passion in programming. Driven by the profound importance of computing in modern society, as well as his desire to create a healthy academic environment for East Palo Alto students, Barhoumi is one of many educators trying to secure the future of computer science in the next generation.

Despite the importance of computing in all aspects of life, and the efforts of those like Barhoumi, computer science surprisingly suffers from a lack of qualified workers. According to Code.org, there will be over a million more jobs created in computer science than people ready to work in the field in the next ten years. Computer science is the only science, technology, engineering and math field where the number of participants has decreased over the last 20 years, down to 19 percent from 25 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

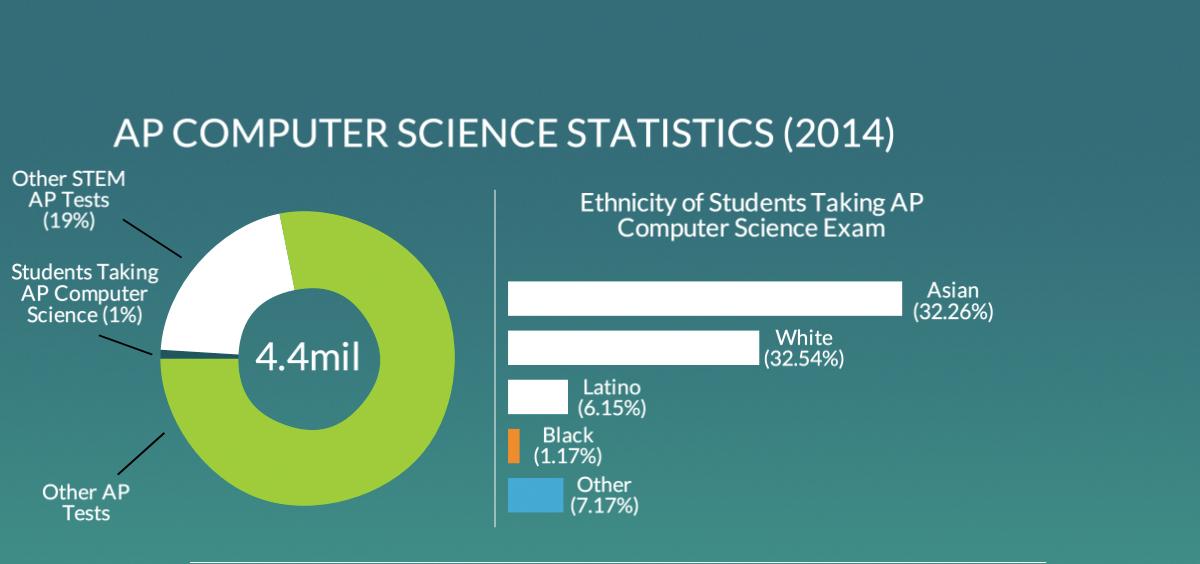

Part of the problem lies in the secondary education system. Only five percent of all high schools offer Advanced Placement Computer Science and, in 2010, only 14,517 students took the AP exam as opposed to the 194,784 students who took the AP BC Calculus exam. This lack of computer programming classes at schools disproportionately affects those with lower incomes who are unable to afford private programming classes and therefore have no opportunities to learn how to program computers while in high school.

In the Bay Area, however, programs have sprung up to combat this inequity. Although both Palo Alto High School and Henry M. Gunn High School have computer science programs, the Palo Alto Unified School District partnered with Palantir, a local, private software company earlier this year, to create a free 10-week-long series of classes on computer programming open to minority and low income high school students. Other nonprofits, such as StreetCode Academy, cater to students not fortunate enough to have other computer science opportunities.

These programs teach students how to use computers effectively, ensuring that the next generation of leaders can ride the tides of computer science to success.

StreetCode Academy

At StreetCode Academy, located on a quiet street in East Palo Alto in what used to be an dilapidated school, students learn fundamental computer science skills. The mission, as stated by Barhoumi, is to empower East Palo Alto residents through classes and internships. The Academy was brought to life this year when Barhoumi and cofounder Rafael Cosman teamed up with local nonprofit Live in Peace to extend their summer coding camp into a year-round opportunity.

“The most important thing at StreetCode is that we want a sense of community and a sense of family,” Barhoumi says.“The whole idea of what we are doing is that we want to provide students with the structure and support that they didn’t have previously … We have unconditional love and support for each other.”

StreetCode, run by computer-savvy volunteers, offers courses such as Computer Science Fundamentals, which meets in the afternoon, and Barhoumi encourages students to attend hackathons — coding problem-solving competitions — on the weekends. Barhoumi’s favorite part about the group is their enthusiasm.

“It’s a self selecting group, this is not public school,” Barhoumi says. “They show up if they want to … because they showed up, they are interested in learning how to code.”

Palantir Classes

Wednesday after school, in a secure building in downtown Palo Alto, 14 PAUSD students sit at an array of tables, engrossed in the code on their computer screens. There is a hushed atmosphere about the room, and clicking permeates the air as students explore applications of HTML, CSS and Javascript. Samuel Vasquez, a Paly junior and East Palo Alto resident, is one of these students.

“I did not take the class at Paly because I thought that it would be hard, but my point of view has changed because I now know more, and it is not as hard as I thought it would be,” Vasquez says.

The classes are part of the school district’s effort to reduce the achievement gap and provide more opportunities to all students.

“The goal is for students in our district who may not have opportunities to access [computer programming classes] because of affordability issues outside of school,” PAUSD Superintendent Max McGee says. “We decided this would be a perfect fit with our initiative around minority achievement and talent development.”

The classes run for 10 weeks, with one two-hour class every Wednesday. They are taught by Palantir software engineers at their headquarters, and they focus on using computers to solve problems.

“The most important thing I wanted the students to get out of the course was a sense of what digital literacy means,” says Ari Gesher, a senior software engineer at Palantir and the main teacher of the classes. “Digital literacy is a slightly larger topic than just knowing how to code. It’s about knowing how to use computers to solve problems.”

According to the Palantir engineers who supervise the classes, they differ from the courses taught at the PAUSD high schools since the classes at Palantir focus mainly on teaching the practical applications of coding.

“It’s a much more theoretical approach rather than a sort of craft approach about how you actually go about the practical aspects of coding,” Gesher says.

Additionally, the individualized approach taken at Palantir makes it easier for students of different skill levels to learn at their own pace.

“One thing that I like from the class is that you can go at your own pace so the class is not too fast or too slow and if anyone gets stuck, the teachers can help them,” Vasquez says. “I like the teachers … and I also feel confident that I can ask them anything and they will know the answer.”

The first 10-week pilot program has been completed, but Palantir and the school district are planning on expanding the program and continuing it later this school year or next year. They plan to make the classes larger and Palantir is working to incorporate student feedback to improve the student experience, according to Mehdi Alhassani, the supervisor of the classes at Palantir.

McGee reports that the classes have been successful, and he hopes to continue offering the opportunity to PAUSD students. He hopes that the classes could spark an interest in pursuing computer science as a career, an impact that could potentially be life-changing for many of the students.

“From what the students tell me, they’ve been really successful,” McGee says. “It’s not only what they learned, but also just seeing Palantir and software engineering as a career opportunity. I mean, they really feel like a part of and connected to Palantir.”

For Vasquez, the classes have opened up new fields and opportunities.

“I have learned many skills when it comes to computer science, and also, I have learned the work that it takes to create software,” Vasquez says. “I am considering this as a career, and I plan to take more classes to teach me more about this because this is a good skill to have.”

Importance of Computer Science

The field of computer science is rapidly expanding to include industries that combine computer science with other fields, adding to the growing necessity of learning computer skills for the future job market. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, computer science jobs will make up over half of the job openings in STEM by 2020. These jobs are exceedingly well-paid, but unfortunately, few minorites, women, or low income students major in Computer Science in college. One of the main problems may be that they are exposed less to the field as children.

“[At an event] an engineer … talked about how a lot of women take computer science courses in college as an elective or when it’s too late to really focus on that and they wish they would have and I think that’s perfect for some of our students,” says Judy Argumedo, head of PAUSD’s Categorical programs and the Voluntary Transfer Program. “If you get in a class right now, you may really like it and be motivated to take it.”

In fact, only 22 percent of Paly students know how to program computers even though 38 percent have taken a computer science class either at Paly or elsewhere. In contrast, 42 percent say they want to learn how to code and 20 percent aren’t sure. According to McGee, he hopes to expand the computer science program so that students are able to learn these skills earlier.

“I have recommended that we formally incorporate computer science into the curriculum in grade seven,” McGee says. “Primarily as an elective but at least students have the option to take it from grade seven through 12.”

Computer science is growing increasingly important as technology becomes widespread in every aspect of life.

“Computers are billions or trillions times more powerful than human thought … for the things they are good at,” Gesher says. “If there is any way to leverage the power of computers to solve your problem, you are going to outstrip anyone else who tries to do it any other way. … As we find new ways to apply software to old problems or sometimes to new problems, it’s completely transformative.”

Being able to use computers can help people regardless of whether or not they become computer programmers, according to Alhassani. For example, computer programming can be combined with science, statistics, psychology or other fields of study.

“Not everyone who takes this class is going to be a coder down the road,” Alhassani says. “But just to have the knowledge of how code works is in itself useful. We have a lot of people at Palantir who are not coders, but they know how it works, and they are able to have good jobs because of that.”

Gesher echoes this thought and argues that in fact digital literacy, or the ability to leverage computers to find solutions, will be absolutely necessary for those who want good jobs in the future.

“We are seeing this with the growing wealth divide,” Gesher says. “If you can get on one side of the divide where you are a knowledge worker and you can make these powerful machines do things in the world, your opportunities are manifest. And if you don’t, your job is basically to do things that the robots can’t do well.”

Gesher believes that proficiency in programming, while important, is only a part of digital literacy. While being able to manipulate computers magnifies a person’s processing capability, innovation can only be achieved through exploring and hybridizing different fields with computer science.

“When we talk about people being left behind, it’s not necessarily that you have to learn how to code, its that you have to understand that this is the way that computers are an incredible amplifier of human effort,” Gesher says. “And if you know how to assemble or design those solutions, then you’re riding the train, to use an industrial revolution analogy. If you’re not, then you’re watching the train go by.”

The student poll results collected for this issue are from a survey administered in Palo Alto High School English classes in January and February. Eight English classes were randomly selected, and 156 responses were collected. The surveys were completed online, and responses were anonymous. With 95 percent confidence, the results for the questions related to this story are accurate within a margin of error of 4.91 percent to 6.51 percent.