Former Palo Alto High School principal Phil Winston was many things. He was a colorful presence on campus. A jokester. A gregarious guy beloved by parents and students alike. In fact, he even took a lax attitude towards streaking, considering it a student tradition. Due to Winston’s casual demeanor, it was common to hear students call him “Chill Phil,” instead of the formal “Mr. Winston” when they saw him around campus.

But there was another side to “Chill Phil.” He made inappropriate remarks to students about their clothes, relationships and even — in an incident cited in a 2013 formal notice of “unprofessional conduct” — “asked if [a student’s] boobs hurt when [she] was running naked through the quad.” Winston had an attitude and ego that carried over into his relationship with faculty, especially female staff members, and reflected the leniency of his adherence to proper workplace behavior.

In June 2013, after three years of aggregating 25 complaints of sexual harassment made by faculty members against Winston, one of Paly’s assistant principals — identified as current principal Kim Diorio by the Palo Alto Weekly and Verde Magazine — was faced with the harrowing choice of whether or not to come forward with the complaints that Winston had played a direct role in cultivating a “sexually hostile environment” at Palo Alto High School.

On one hand, Diorio was concerned for women and girls on campus, and wanted to confront the hostile environment.

On the other hand, she feared retaliation against both her and her colleagues. Not only was Winston her direct superior, but the misogynistic environment she saw at Paly was prominent at the District Office in the form of, as one staff member put it, a “good ole’ boys club,” according to redacted documents published by the Palo Alto Weekly.

To her knowledge, Diorio had no obligation to report the complaints, she wrote in a letter to Assistant Supt. Scott Bowers. Even so, she felt a duty to take action. She grappled with the idea of confronting Winston directly, but ultimately decided not to, afraid of making the situation worse. Instead, she scheduled a confidential meeting with Palo Alto Unified School District’s Title IX coordinator at the time, Charles Young. Young’s job was to deal with everything related to Title IX, a federal education law that states that no person should be discriminated against on the basis of gender.

Ultimately, Diorio did voice her allegations against Winston. In her letter to Bowers which was sent a week following her meeting, she stated, “[coming forward was the] most difficult professional decision and conversation that I’ve had during my time with the District.”

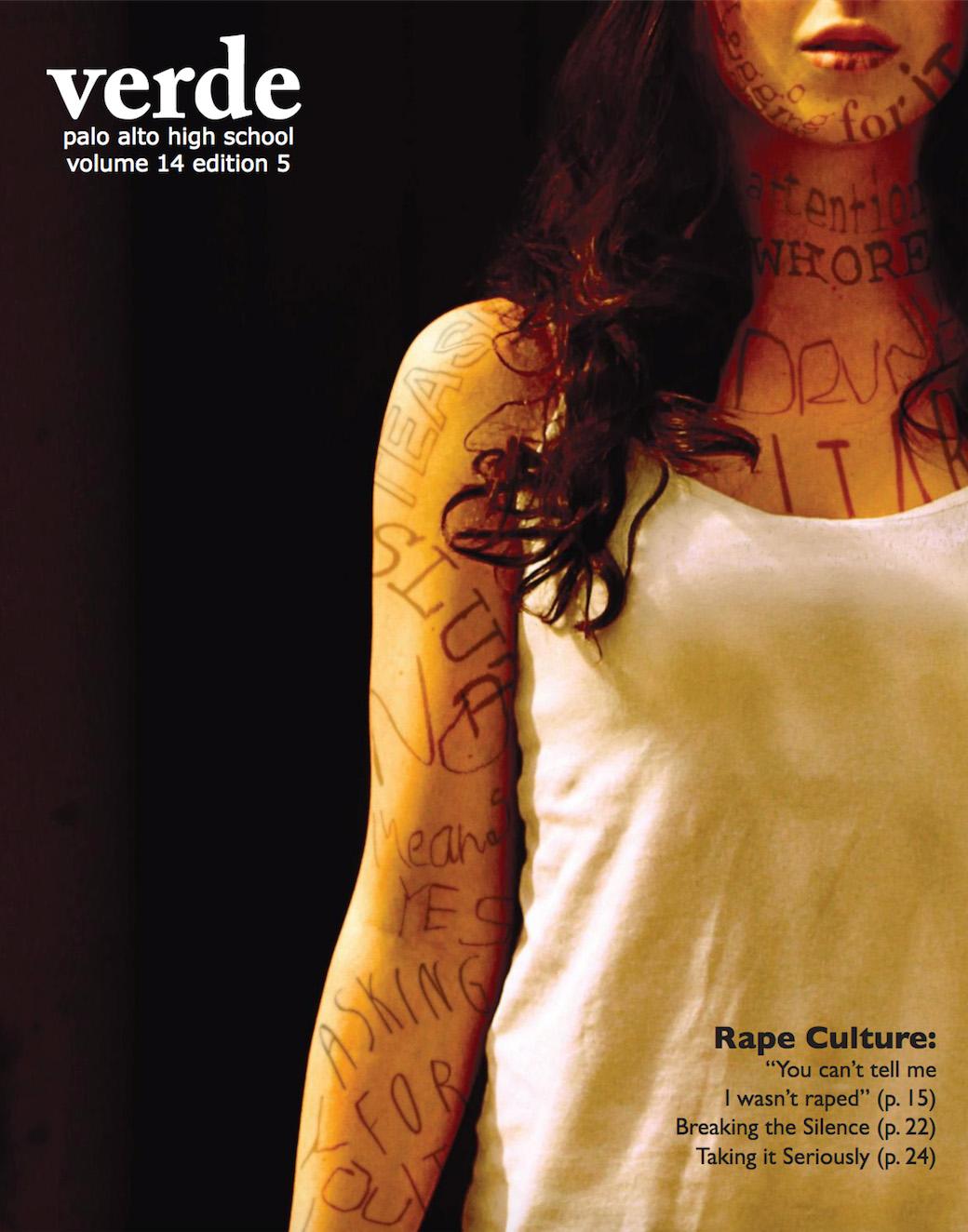

Soon after, citing health reasons, Winston resigned. Around the same time as a nation-wide dialogue about sexual assault loomed over the community and the release of Verde’s “You Can’t Tell Me I Wasn’t Raped” cover package, an Office of Civil Rights investigation was launched into whether the district, by improperly applying procedures for reporting sexual assault, had also helped cultivate the sexually hostile environment described in Diorio’s letter.

The OCR, a sub-agency of the U.S. Department of Education, works to investigate and eliminate discrimination in educational institutions. Sexual harassment and assault, forms of sex discrimination, fall under the office’s jurisdiction, as, according to Michele Dauber, a Stanford professor of law and Title IX expert, “It could really impact your ability to get an education, depending on how severe it is, how pervasive, how extensive [it] is.”

Early this year, the OCR released the findings of its investigation. In it are eight cases of reported assault or harassment, all critically examined to determine whether the district mishandled them.

The 23-page report unequivocally states that the process in which these cases were addressed by the district was broken. It also criticizes the redacted assistant principal, Diorio, as having improperly withheld three years worth of allegations against Winston. In particular, it condemns Diorio for not discharging “her responsibility to take immediate and appropriate steps to address them when they were reported to her,” given her position as a high level District employee.

“Under the law, that staff member had an obligation to report [them],” Dauber says. “The law is what it is but I am not unsympathetic to that employee saying that she … feared retaliation. We shouldn’t downplay the very real fear people have of retaliation when they report things like this.”

Ultimately, the OCR report should be viewed as not just a formal examination of the district, or a criticism of some far-removed administration. It is a story of the complexity of our culture, one in which stigmas control the narrative, victims are pushed into silence and a culture of shame simmers underneath the reports, facts and redactions. Diorio’s story is one of many.

In a school with a history of leaving the suffering in silence, Diorio says she is striving to guide Paly into a new age of transparency and efficacy.

“My only regret is that I did not come forward sooner,” writes Diorio in her 2013 letter to Bowers.

Where it all began

The story of the OCR investigation in PAUSD began almost four years ago to this day

on April 8, 2013. That’s when Verde released “You Can’t Tell Me I Wasn’t Raped,” a cover story which detailed narratives of Paly students who had survived sexual assault, and identified a largely unrecognized rape culture, an environment in which incidents of sexual harassment and assault are considered normal or acceptable because of norms and values, on campus.

The impact of the cover story would prove to last well beyond the days Verde spent in the spotlight, and would eventually catalyze a four-year long investigation by the OCR into cases of sexual harassment within PAUSD.

Dauber was one of the first voices who called upon the school board to conduct an internal investigation of the handling of sexual harassment cases. Dauber’s efforts grew out of her long-standing concern and activism in connection with the district’s response to a 2013 case of “disability bullying” at Terman Middle School.

“Right as the community was wrestling with this issue, the Verde article came out and I said ‘Oh my God, it’s the same exact thing,” Dauber told Verde. “The standards [for Title IX] are not different depending on whether it’s sex or race or disability. It’s the same. You have to investigate promptly and equitably and take steps to stop the hostile environment.”

“On one hand I was proud of our student press who really understood the impact that this story could have,” Diorio says. “At the same time I was so disheartened … and thinking ‘Wow. How do we talk about this and how do we do more to address what’s happening?’”

Now, four years later, the OCR report provides answers to these questions.

“There was part of me that feels very relieved that we have some closure to their investigation and the resolution agreement provides us with an action plan for moving forward.” Diorio says. “But the findings itself were in some way difficult for me to digest, because I know so many of the personal stories and shared experiences of the different people who are involved in the [OCR] investigation.”

District defiance

After Diorio came forward with the staff allegations and the OCR investigation began on June 3, 2013, the superintendent and board responded with staunch resistance to components of the investigation. In 2014, the board passed a resolution condemning the OCR for methods used when conducting investigations.

According to Diorio, a lack of knowledge on the intentions of the OCR ignited opposing opinions.

“I don’t have enough information for why that decision was made in 2014 and why the board took action the way they did,” Diorio says. “I think because we were one of the first public secondary school districts to be investigated by them [OCR].”

A pervasive fear of the unknown permeated the board at that time, according to Diorio, as members had to deal with an unfamiliar query from an unfamiliar source. Eventually, however, the board would accept the OCR and its findings, passing a resolution early this year reversing its 2014 criticism.

What lies ahead

Four years later, although the OCR investigation has come to a close, the community’s work is only just beginning. According to Diorio and Supt. Max McGee, in addition to classroom lessons on sexual harassment, additional measures will be taken to expand the discussion, as dictated by the agreements with the OCR.

To destigmatize the topic and empower students, PAUSD is planning assemblies with dynamic speakers to educate students and staff on complex issues including sexual harassment and assault. Annual student surveys will help administrators get a sense of school climate, and this information will be monitored and tracked by the OCR to ensure progress. Revised Title IX policies and procedures will appear in the Student Handbook and classrooms to help students understand them.

These are steps in the right direction, according to students who have formerly dealt with assault and harassment.

“Never talking about it creates a barrier between victims and those who couldn’t imagine what it’s like,” says Kristie, an assault survivor and current student whose name has been changed to protect her identity. “When we begin talking about sexual assault, it removes the stigma around it.”

The OCR and the district also are working to create an anonymous reporting tool to encourage students and staff to speak out without fear of retaliation and with confidence that action will be taken. Diorio says these efforts are meant to open lines of communication between students and the administration, as well as combat the stigma that silences so many victims of sexual harassment.

“If you feel you’re being treated in a way that doesn’t make you feel welcome or doesn’t make you feel safe, then we want you to report that to us,” Diorio says. “We want to know about it. The challenge is, we can’t fix something if we don’t know it’s an issue. So how do we create a mechanism where students feel they can report something in confidence and then know the school will take action and follow through?”

Perhaps most crucial to adapting the school to the OCR investigation is ensuring that faculty know how to properly handle cases of sexual harassment and can promptly and equitably report such cases to the school district.

“I don’t think anyone failed to respond or didn’t respond timely enough because they didn’t care,” Diorio says. “I think it was more of not really knowing what the next steps should be.”

Case closed?

Moving forward, despite the conclusion of the OCR investigation, many people are still left with unresolved questions.

“Is it just a net bad coincidence?” Dauber says of the multiple cases explored by the OCR. “I am concerned because I don’t understand what is going on in the culture of our community that has made a space for that kind of thing. That’s a high number for such a small district.”

Another major unresolved question is how the district ultimately will view Diorio’s decision to withhold the 25 complaints until her moment of truth. According to social sciences teacher Eric Bloom, the report’s allegation does not negatively affect his judgment of Diorio’s abilities.

“I am actually more confident in her ability to lead this campus after having read the findings of this report,” Bloom says. “Diorio now has the experience and evidence to bring about change and challenge the misogynistic mindset of women having to be less sensitive.”

McGee also commends Diorio for setting clear guidelines as to what actions are and are not appropriate.

“There’s a saying that … you deserve what you tolerate,” McGee says. “If you have adults saying ‘This is just kids being kids’… [and] pass it off as just something trivial, you’re really opening the door to tolerating other behaviors which just lead to more inappropriate actions. I think she [Diorio] has made it very clear [which] actions by students and adults just aren’t going to be tolerated.”

Diorio, along with the rest of the PAUSD faculty, is now tasked with ensuring the most efficient mechanisms are put in place so sexual harassment is dealt with promptly and equitably.

“We are here to accept all, protect all and we’re proud of it — that needs to be what our culture’s all about ,” McGee says. “We still have more to do [but]… I think our culture shifted from ‘this is something I have to do’ to ‘this is something worth doing.’”

Diorio says she knows how difficult it is to come forward — now, she says she is leading the effort to make sure students don’t face the same fear of retaliation that she did.

“Four years later we are a different school and we are at a different place and different point in time and that’s the good news,” Diorio says. “We’ve learned a lot from our past mistakes and failures and I think we’re better now at supporting kids and supporting staff members — supporting people who have these experiences or are afraid to come forward.”

Read more about the OCR investigation and the eight cases they detailed in their findings.

Correction: May 16, 2017

An earlier version of this misstated the date the investigation began. The investigation began on June 3, 2013.