They waited until the light faded from the sky and the moon rose to its peak. Cloaked in the darkness of midnight, they fled.

“Families would cast out in boats with 200 other people on them — these tiny little fishing boats — with really nothing except the clothes on their backs,” Tiffany Lieu says, describing her parents’ escape as teenagers from Vietnam during the war 40 years ago.

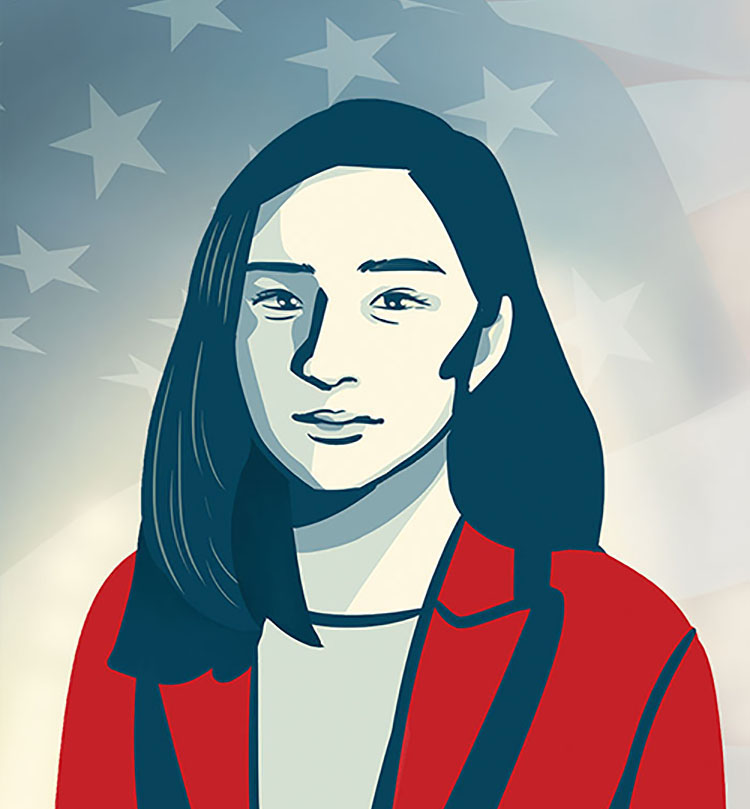

We met with Lieu at Peet’s Coffee across the street from Palo Alto High School and a mile away from the Stanford Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, where she works as a student immigration attorney.

“You would cast out in hopes that an American oil tanker or French oil tanker would rescue you and then you would seek refuge that way,” Lieu says. “There were many boats that never made it — so it was an incredibly dangerous journey.”

When the Socialist Republic of Vietnam took power, Tiffany Lieu’s parents were two of countless refugees uprooted by guerilla fighters, widespread bombings and government persecution during the Vietnam War.

Behind them, Lieu’s parents left everything: their home, their friends and a lifetime of memories. They left with no specific destination in mind and with no plan except to get away.

It was pure luck that they survived the perilous voyage and, after a temporary stay in Malaysian and Hong Kongese refugee camps, made their way to the United States. When they arrived, they were warmly welcomed by a host family who helped Lieu’s parents settle into their new lives.

Now, as Syrian refugees like the boat people fleeing Vietnam face a perilous journey to reach safety and a resurgence of xenophobia rekindle disputes over immigration, their daughter carries the torch for immigrants seeking haven in the U.S. As a Stanford Juris Doctor candidate and immigration lawyer-in-training, Lieu hopes to pass forward the compassion shown to her parents. “It’s part of the reason why I went to law school in first place,” Lieu says. “It was the kindness of strangers, really, that helped my family get their feet under them after being totally torn away from their homes. That’s something that’s really stuck with me — knowing that that kind of generosity helped my family so much makes it doubly important for me to try to do that for other people as well.”

“It was the kindness of strangers, really, that helped my family get their feet.”

– Tiffany Lieu, Stanford immigration lawyer

Family history

Growing up in Seattle, Lieu led a very different childhood than the one her parents experienced in Vietnam. Nevertheless, her family’s trials as refugees and immigrants shaped Lieu’s upbringing with a heavy hand.

She recalls how her grandmother would become infuriated whenever Lieu didn’t finish her meals and would always tell her to put on a coat before she left the house, no matter what the weather.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t understand why … but as I grew up I became more interested where those concerns stemmed from and I started digging into my family’s history,” Lieu says. “My grandma’s experience of having nothing, leaving Vietnam and being thrust into a refugee camp where there was a lot of struggle … I think that that was her way of telling us to be very thankful for what we have.”

When they arrived in America, Lieu’s parents faced the immense struggles of learning a new language and assimilating into a new culture. Because of their own challenges, many of which stemmed from a lack of knowledge, they stressed the importance of education and diligence when raising their children.

“My parents sacrificed so much for my siblings and I, and they really prioritized our education above all else,” Lieu says. “Part of the reason my siblings and I work so hard now is because … of how much sacrifice my family has gone through to bring us to where we are today.”

Lieu’s drive, bolstered by support from her parents, brought her to Duke, where she earned a degree in history and English, and later to Stanford Law School as an immigration lawyer-in-training.

“I’ve been interested in immigration since I found out more about my own family’s history,” Lieu says. “There’s a whole range of reasons why people come. Lawyers fit in in terms of fighting for their rights to stay in this country and fighting for rights that they have once they’re here.”

Defending due process

Instead of protesting and holding rallies like traditional activists, Lieu wields the power of law to advocate for equal treatment of immigrants.

“I’ve been to a detention center and when I went, it felt like you were in a prison,” Lieu says. “Because it’s civil detention, it’s not treated the same as a prison … I don’t think that immigrants have the same rights as citizens and I think that’s problematic on many levels.”

As an immigration lawyer, Lieu works to fight against such injustices. Through work in the Stanford Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, Lieu learns to use the law to defend her clients. “Having people who are passionate about immigration go into representing immigrants is extremely important,” Lieu says. “As students, we’re being trained, but we’re also being exposed to these very important issues and being able to help clients early on.”

Under the guidance of senior lawyers like Lisa Weissman-Ward, one of Lieu’s mentors and a supervising attorney of the clinic, young lawyers are able to change the lives of their clients in the court of law.

“It [the clinic] gives students an opportunity to see in real time and in real life the impact of a network, the impact of working in community, the impact of having a lawyer,” Weissman-Ward says.

“Being able to see that in real time and actually experience it is an incredibly powerful tool.”

The impact of lawyers extends beyond paper; outside of defending clients in court, they also have a profound impact on the local and wider communities.

“By virtue of the fact that they [undocumented immigrants] have an attorney, their odds of having a successful outcome are already exponentially increased,” Weissman-Ward says. “Not only do we want to provide them with a critical right to due process, it’s also about community empowerment and providing a space where our clients can be heard and seen for who they are, not whether they have a piece of paper or a certain criminal record.”

“Every single person here was an immigrant at some point.”

– Tiffany Lieu, immigration lawyer

In Lieu of discrimination

According to Lieu, immigration is the foundation of a fundamental aspect of America: its diversity of opinion, people and culture.

“Every single person here was an immigrant at some point,” Lieu says. “Everyone has different reasons for coming. Having that diversity is incredibly important to the community and the country.”

From her personal background and her work as an immigration lawyer, Lieu is a firsthand witness to the importance of immigrants.

“We are a nation of immigrants,” Lieu says. “Being able to have people come and not be discriminated against is vital to who we are as a country and as a people. My own family’s history documents that.” v