With tensions running high in the Palo Alto Unified School District meeting room, school board member and chair of the Board Policy Review Committee Camille Townsend struggles to maintain order. The room is hot and full of angry community members, silenced lawyers and flustered board members.

A parent protests as superintendent Kevin Skelly speaks on the handling of bullying incidents in Palo Alto, and Skelly moves to address the parent’s accusatory question.

“Excuse me, Dr. Skelly, I am the chair of this committee, and you direct comments to the chair,” Townsend says, stopping Skelly from responding to the parent.

A jumble of impassioned whispers, sarcastic laughs and Townsend’s pleas for order fill the cramped space.

“Excuse me, folks, come on, we’re trying to move ahead on bullying,” Townsend says. “We’re supposed to interact with each other in a formal and kind way, and I would like this spot to be a kind place so we can have kind conversations about how our children should get along with each other.”

Palpable tension dies down, but the innate conflict between community and school board members over bullying remains clear.

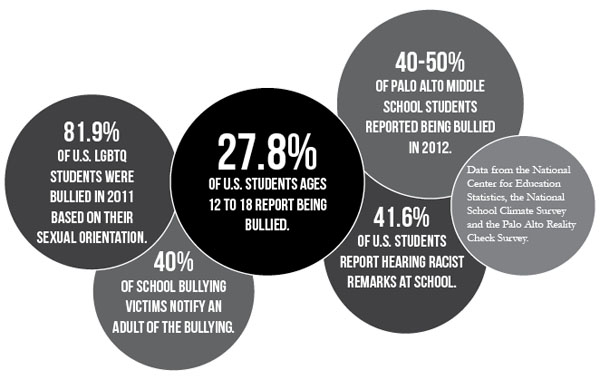

Since January 2014, the Palo Alto school board and district committees have been actively debating and formulating the guidelines of PAUSD’s new bullying initiative. California’s 2012 Seth’s Law requires public school districts to update their anti-bullying policies to focus on protecting students who are disabled, belong to a minority race, or are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender — groups deemed most vulnerable to discriminatory harassment.

The district recently faced the bullying of protected-status students in 2011, when a case of bullying at Terman Middle School involving a disabled student resulted in a lawsuit against the district by the student’s family.

According to Palo Alto Online, the suit claimed that PAUSD did not take appropriate action to handle the harassment of the disabled student. The Office of Civil Rights, a branch of the U.S. Department of Education that seeks to ensure equal educational access to students by enforcing civil rights, found the district’s actions inadequate and unconstitutional.

Multiple incidents of discriminatory harassment have been reported to PAUSD since the Terman case, and this new policy is aimed at preventing similar cases in the future. The updated draft outlines a two-tier policy to handle reported bullying incidents, giving further protections to students who fall into the protected classes such as a set timeline, an appeals process and written documentation of the handling procedure.

According to a Jan. 10 Palo Alto Weekly article, Skelly expressed support during a board meeting on Dec. 3 for a single-tier policy that would handle all bullying cases equally. Two weeks later, after speaking with various district and school leaders, he changed his mind; he now recommends a two-tier policy like the current draft due to its alleged simplicity.

Opponents of the updated, two-tier policy include Michele Dauber, a Stanford law professor who led the drafting of the Stanford Disciplinary, Sexual Assault and Title IX policies three years ago after unsatisfactory statistics and reports on harassment at Stanford arose. She supports the policy that Skelly was pushing initially, the policy that essentially outlined a uniform approach to handling cases of bullying, thereby advocating equal protective measures against bullying for all students, regardless of legal protected status determined by Seth’s Law.

“I am an advocate for following the law,” Dauber says. “I think it is more likely that we’re going to follow the law if we have one policy. I think that’s why CSBA [California School Boards Association] thinks we should have one policy, because I think that mistakes are much more likely the more complex you make the situation.”

According to the California Department of Education, the state grants the legal right to protected class students to follow the Uniform Complaint Procedure, or UCP, when discrimination, harassment, bullying or intimidation directed at them violates federal or state law. The current draft of the two-tiered system, which is available to the public on the PAUSD website, does not specify that cases of discrimination should move up to the higher-tier policy dictated by the UCP, as protocol for cases involving protected class students.

Dauber opposes the newly suggested draft of the policy. According to Dauber, the policy contains wording flaws that could cause confusion and even legal trouble for the district.

“The new policy that’s supposed to apply only to the unprotected classes — regular bullying — now applies to protected class students,” Dauber says. “It [the policy] is already broken, and they haven’t even done it yet.”

Nor does Dauber find recent drafts of the lower-tier bullying policy to be comprehensive in setting clear guidelines for the process the board will follow in cases of bullying. The current online draft, which shows all edit marks, reveals that certain segments of the policy that outlined deadlines for the board when handling bullying cases were removed by policy makers. Since December 2013, the policy has been revised to no longer include a timeline, written decision or appeals process for non-protected bullying complaints.

“[The policy] has no record-keeping documentation, no timeline at all, no requirement ever written, so it violates everything about the law [Seth’s Law],” Dauber says. “Process protects everyone. It protects the accuser and the student who is being accused.”

Skelly attributes the changes made to the policy to the district’s want for as simple, efficient and straightforward a procedure as possible.

“Part of the reason for eliminating that [timelines] is that people [district staff] tend to stretch [deadlines] to the end, and we don’t want them stretching it until the end,” Skelly says.

This lack of timeline or specific procedure affected the family of Kate, a mother whose name has been changed to protect her daughter’s identity. Her daughter has been out of school since Jan. 12 due to persistent bullying that Kate claims was not appropriately addressed by PAUSD.

“The principal was ready to jump at us when I went to her for a meeting,” Kate said in the March 12 school board meeting. “She wouldn’t let us have any advocates for our side. … Who do we have to help us? No one. Our kids have to go school, it’s the law. I’ve been trying to work out an appropriate placement for her [her daughter]. No one ever calls us back. Who is here to help the children? No one.”

Three years have passed since the initial Terman case and the drafting of a new policy, a delay that has become the source of common complaints that little has been accomplished in establishing an appropriate anti-bullying policy for all students since that 2011 wakeup call. Brenda Carrillo, the coordinator of student services for PAUSD and the leader of the committee drafting the policy, attributes the delay to the lengthy process of receiving and implementing feedback on the policy from the school board and the Palo Alto community to try and create the most comprehensive and satisfactory policy possible.

“We’re really striving to have a holistic approach, and we’re not just focusing on bullying, we’re focusing on school climate in general,” Carrillo says. “We’re constantly striving to improve in making sure that students can go to school to learn.”

In its attempts to solve this problem of bullying, PAUSD added a page titled “Bullying Prevention” to its website in early 2014 to involve the community in drafting the policy while also informing concerned district members on issues surrounding the boundaries and available support for bullying. The site defines bullying as “any severe or pervasive physical or verbal act of conduct, including made in writing” that involves sexual harassment, hate violence, threats, harassment or intimidation.

Now, Carrillo says that her committee hopes to consolidate the two-tiered policy to create one uniform procedure for all students. The school board has not yet approved such a proposal, but according to Carrillo, community feedback seems to favor it.

Alexander Davis, a Palo Alto High School social studies teacher and the teacher adviser of the Queer Straight Alliance Club, understands the rationale behind a two-tiered system, but advocates a uniform policy.

“Bullying someone on the basis of hair color, weight or academic performance can have as much to do with identity as race or sexuality,” Davis says. “We need a uniform policy for dealing with cases of bullying.”

Skelly commends Palo Alto’s general atmosphere of safety and acceptance, but notes that there is no perfect solution to a problem as broad and controversial as bullying.

Skelly commends Palo Alto’s general atmosphere of safety and acceptance, but notes that there is no perfect solution to a problem as broad and controversial as bullying.

“We have a community here that is one of the safest to go to school in,” Skelly says. “I think this is some of the hardest work we do. There is no solution where all those people [in Palo Alto] will be fully satisfied and where there isn’t an element of people feeling unresolved.”

Dauber says that many Palo Alto residents do not realize how important of an issue bullying is, even in a seemingly placid community like Palo Alto. She blames the notion that an affluent and liberal city would be devoid of issues like discriminatory harassment.

“In Palo Alto, there’s a little bit of a prevalent attitude of ‘Don’t they know who we are?’ going on, and I think that’s a real impediment,” Dauber says. “We all have to color in the lines. The law applies to everybody. That’s what democracy is.”