The names of junior Miranda Jimenez and her two younger brothers — Xavier and Sebastian — hide a duality of language. Their parents wanted their children to have names that could be pronounced both in English, with its staccato short vowel sounds, and Spanish, with the rolling “r’s” and drawn out “a’s.”

And just like her name, Jimenez straddles two worlds. Although her parents were born and raised in the United States, her paternal grandparents hail from Mexico; Jimenez’s dad, who is a near-native Spanish speaker, encouraged her to learn the language growing up through songs and stories. Still, maintaining roots that are displaced two generations in the family does not come easily, explains Jimenez, who currently takes Spanish 3 at Palo Alto High School.

“A lot of my friends are like, ‘Miranda, you’re Mexican, you should know more Spanish,’” Jimenez says. “And that’s a joke, but I wish I did know more Spanish. I feel like I should know more just because of my dad and my grandparents. I feel like I had the resources.”

For three Palo Alto High School students with different cultural backgrounds— a freshman, a junior and a senior — though their words vary, their search to integrate an identity that is inherently part American and part foreign through language is universal.

Their stories reflect the larger population of Paly students with immigrant families; while some read, write and speak their parents’ native language with complete fluency, others know only enough to ask for directions. Experiences with language also tend to fluctuate throughout life: many students who were once reluctant to learn their parents’ language strive to reclaim it as they grow older and gain an appreciation for their heritage.

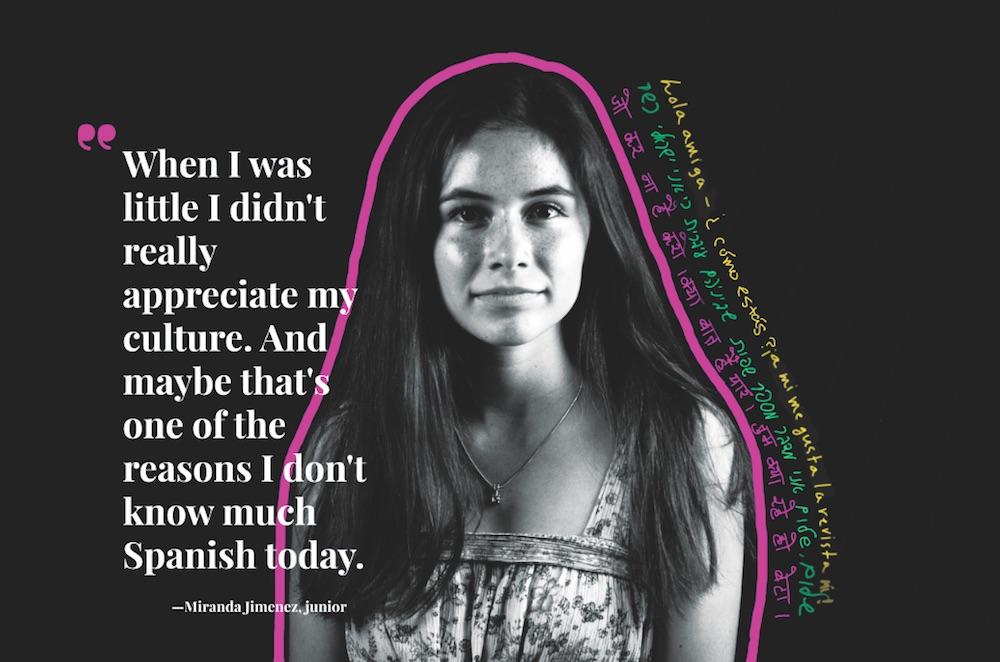

“When I was little I didn’t really appreciate my culture … I thought it was weird — I wanted to fit in.”

— Miranda Jimenez, junior

“When I was little I didn’t really appreciate my culture,” Jimenez says. “And maybe that’s one of the reasons I don’t know as much Spanish today. I thought it was weird — I wanted to fit in. But now I’ve grown to appreciate the language and the culture … but I still haven’t connected as much because of how I was when I was younger.”

For seniors — many of whom will be leaving their physical roots and moving several hours away for college in a mere couple months — the worry of losing touch with a culture and language now displaced even further is particularly acute.

“All of us will naturally gravitate towards finding communities that we’re comfortable with in college,” says Paly Sociology teacher Benjamin Bolaños. “And so the question for children becomes, how much do you assimilate? How much of the native tongue and how much of the language and the culture and the customs do you keep as a Chinese-American or Japanese-American or Latino?”

Cultural connections

“Jo kar na hai karo” — literally meaning “do whatever you want to do” in Hindi — is an ironic response senior Ujwal Srivastava often receives from his mother, Ashini Srivastava, when she doesn’t agree with a decision he’s about to make. At the same time, English analogues of the phrase are also heard routinely around the Srivastava household. In their home, Hindi and English rhythmically bounce off each other. From dining table discussions to playful conversation, a complete sentence frequently starts in one language and ends in the other.

“They just slip off out of our tongues so easily — we don’t even realize when we’re switching between languages,” Ashini says. “Sometimes subconsciously you start thinking in two languages … and I think it somehow improves your expression when you read, when you write and when you speak.”

This fluid “Hinglish,” equal parts Indian and American, mirrors the Srivastavas themselves — a first-generation family in Palo Alto originally from North India, they embrace their Indian roots while simultaneously welcoming American culture.

“The thing I appreciate most about how they [my parents] balanced the cultures is that they never told me one or the other was right or they never forced me into one,” Ujwal says. “At the end of the day they were very open. … They never were like, ‘Oh, you need to be more American’ or ‘You’re being too American, stay with your cultural values.’ I think it just naturally came about that I found a balance of both worlds.”

But as much as the Srivastava family has been able to integrate both languages, considering the meaning of “first-generation” compels Ujwal to pause before responding — it’s a bit more nuanced than that. Although Ujwal was born in Palo Alto, at age four his family returned to North India. Ujwal credits his native-like fluency in Hindi to the colloquial slang and cultural understanding he picked up from these five years of living in the heart of New Delhi — components he says cannot be taught in a classroom. In turn, his fluency in the language provides him with a sort of front-row seat into India and its culture.

“Understanding the language is a lens into understanding the culture of a place,” he says. “It [being bilingual] has given me a lot more appreciation for both Indian and American cultures, because [for] a lot of the things — to understand the values and how people view things in that society — being comfortable with the language is a great way to do that and I would almost say it’s a prerequisite to doing that.”

With his permanent move back to Palo Alto in third grade, however, most of his formal education in Hindi ended. Still, in the absence of workbooks and lectures, both Ujwal and his sister began to pick up the pieces through their own means: vibrant music, cuisine, Bollywood cinema and pop-culture entertainment.

“[Being bilingual] has given me a lot more appreciation for both Indian and American cultures.”

— Ujwal Srivastava, senior

Ashini says she was initially dissatisfied with her children’s lack of more explicit Hindi practice. She recalls that years before becoming a mother, she decided that her children were to grow up speaking Hindi in the household, regardless of whether they lived in India. But as Ujwal grew steadily more preoccupied with schoolwork, she says she came to realize that he was staying in touch with Hindi and Indian culture — just in his own way.

“It gets hard for the kids because they are trying — especially if they’ve lived away from the country — they are trying to get back and reorient themselves and relearn some of the cultural things,” Ashini says. “And if they’re trying to keep up with schoolwork and if that’s too much of an added work burden on them, at some point they would resent it.”

Jimenez’s father, on the other hand, has a slightly different take on bilingual parenting. Although his own parents tried to speak English extensively to him when he was growing up, wanting him to assimilate into American culture, when raising his own family he strongly encouraged his children to learn Spanish. He also enrolled Jimenez’s younger brothers in Palo Alto Unified School District’s Spanish Dual Immersion Program at Escondido Elementary School; as a result, there’s a disparity in Spanish fluency among her family, Jimenez says.

“I think he [my dad] realized that that [Spanish immersion] was the only way to keep it going,” she says. “And … they [my grandparents] will talk to my brothers in Spanish but it’s kind of awkward because I’m not really good at Spanish and it’s hard for me to talk to them, which is sad.”

Despite the differences in the languages they speak and their fluency in them, both Jimenez and Ujwal agree that language is a powerful force in shaping identity. For Ujwal, bilingualism strengthens the link between his two worlds, Indian and American.

“Being Indian-American is a huge part of my identity. It basically is my identity,” he says.

Though Ujwal can’t quite remember who he first heard it from, he grins, recalling a quote that he says resonates with him. He delivers it with an astute confidence:

“I’m 100 percent Indian and 100 percent American. If you can’t do the math it’s not my problem.”

Tongue-tied

Freshman Maya Hoofien doesn’t go to synagogue. She was born in Seattle, Washington — nearly 7,000 miles away from her parents’ homeland, Israel. She has almost no friends her age who speak Hebrew, and she describes her exposure to the language as almost entirely “confined” to her blood relatives. And yet, in order to communicate with her extended family — all of whom live in Israel — Hoofien has no choice but to maintain fluency in Hebrew, a language and piece of a culture she has ultimately grown to cherish. Still, she says, despite Hebrew technically being her first language, maintaining it while being the “first American kid” in her family is a constant, conscious choice.

“It’s hard choosing — actively choosing — to be different,” she says. “There was kind of a switch in me maybe a year or two ago: I decided I want to put effort into this, I want to speak it … and read it more quickly and fluently. It was hard to do that, but I decided to and now it makes me very happy. I’ll catch myself just completely being able to talk about whatever I want to with my grandparents on the phone and it brings me so much joy that I don’t have to fight for it, that it’s there. It’s my language, a part of my culture, and I can speak it.”

This “switch” to reclaim a deeper connection with language and culture came only after years of struggling to understand how her Jewish and American identities fit together. In Israel, cultural differences that manifested themselves in language singled her out as an outsider.

“It’s like you can’t win, because I’m not Israeli there and I’m not American here,” Hoofien says. “There I’m the American granddaughter and here I’m the Israeli girl.”

Here, Hoofien says, it is often easier to hide her background in favor of fitting in — her last name is Dutch rather than Jewish, and she sometimes chooses to speak to her parents in English when in front of others.

“There I’m the American granddaughter and here I’m the Israeli girl.”

— Maya Hoofien, freshman

“It’s so easy to pull away from it,” she says. “I look like I could be from anywhere in Europe. And so it’s easy to want to … pass for not being what I am and not to bring it up. Like that my mom’s name is Orit and that she’s from Jerusalem — not mentioning those things is so easy. And it’s even easier to sit there and not have someone have a list of things about you going through their head before they’ve met you.”

With fitting in, however, comes a pang of guilt and a compelling pull to connect back to her roots, Hoofien says. Combine this with the fact that Paly offers no Hebrew courses, and finding harmony between her two lingual worlds — English and Hebrew — becomes difficult. Hoofien recalls a time when her mom reprimanded her after finding out that she had participated in a Secret Santa with her friends as an illustration of this precarious balance.

“She was like, ‘You’re forgetting your culture!’” Hoofien says. “And I was like, I bought my friend two lip balms, that’s a little excessive. … I care about my culture a lot. But being Jewish and Israeli culturally but not being a part of the religion is a very difficult line to draw because there are elements that I just can’t associate with … so one of the biggest things for me is the language.”

Bolaños explains that for bilingual students like Hoofien, deciding which language and culture to associate with is often not an independent choice. Instead, their identities are cast and molded by the worlds around them.

“You’ve got to code-talk,” Bolaños says. “People who are not bilingual or bicultural don’t understand that you play different roles with different communities because you have to.”

Additional reporting by Myra Xu