Daiki Minaki explains that the kendo ranking system comprises two sections, the kyu and the dan. Kendoka, those who practice kendo, start at 6-kyu and work their way up to 1-kyu, before moving on to the dan system. From there, they progress from 1-dan to the highest rank of 8-dan.

Two guttural yells ring through the dojo as masked figures lunge toward one another. Through their explosive shouts, the warriors announce their attacks immediately before the strike. The cuts are quick, and the three referees promptly raise their flags in response, touting the victor.

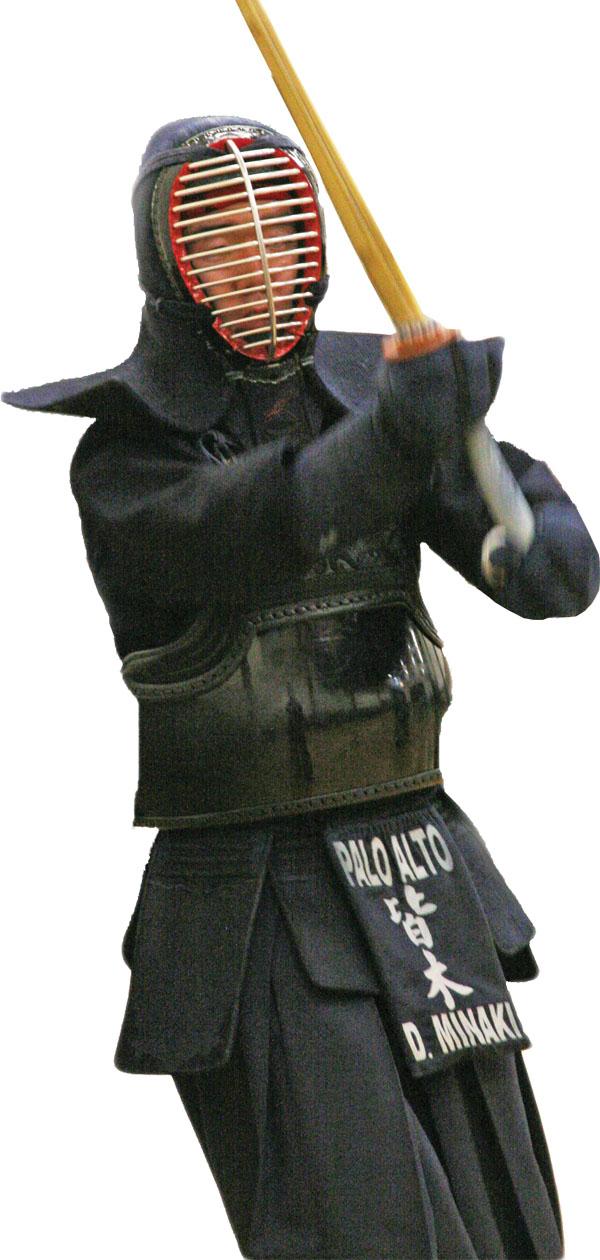

Though they are loud, the two students are only part of the focus. With six to eight matches happening at any given time, the stomps, yells and strikes all blend together under the high arched roof of the dojo. Palo Alto High School senior Daiki Minaki’s calls only contribute to the din as he trains against a fellow kendoka.

Minaki began his kendo training at the age of 13, visiting a dojo once a week with his dad. He now travels to different dojos, practicing more than three times a week for at least three hours. His dedication has paid off — just last year, Minaki placed first in the 1-2 dan division of the Northern California Kendo Championships.

Minaki is currently preparing for the All United States Kendo Federation National Championships in San Diego in May. Though this championship takes place every three years, Minaki attends six or seven competitions annually.

“I try to go to as many tournaments as I can — competitions are my favorite part [of Kendo],” Minaki says. “I like going in with my team and getting really pumped. Winning just feels really awesome.”

Although martial arts often evokes images of aggressive kicking and chopping, according to dojo instructor George Nishiura, kendo is less about force and strength; the kendoka instead relies on speed and endurance.

“You have to be focused,” Nishiura says. “[In] kendo, something happens in a split second. It’s the fastest sport of any sport … focus, reflexes and concentration; I think it’s the innate nature of kendo.”

Minaki agrees that a lot of his kendo skill comes from the mind, not the body.

“There’s a lot of physical training,” he says. “But you also need a lot of mental discipline if you want to succeed.”

According to Minaki, kendo’s resulting mental discipline helps his productivity when it comes to academic work.

“I’ve been able to push myself, and I can work a lot harder because I put a lot of time and effort in kendo,” Minaki says. “That translates into my schoolwork. If I really don’t want to do something, I can now force myself to do it.”

However, kendo contributes to more than just the individual mind. According to Nishiura, the mental discipline kendo requires extends to a kendoka’s everyday character.

“The main subject of kendo is not hitting each other, but trying to build character that’s good for society,” Nishiura says. “[Minaki] takes the training very seriously … it makes him a very dependable person. If I ask him to do something, he does it. There is no question asked.”

Kendo’s focus on good character is reflected in the competition evaluation. At tournaments, kendoka are ranked based on their kendo skill and their spirit and respect for their opponents. The kendoka cannot progress through the ranks unless they show good self-control.

Minaki doesn’t have any specific plans for the future of his kendo career, but he knows he wants to continue advancing his current rank of first dan after he graduates.

“I want to get at least to fourth dan,” he says. “I might take a break in college, and start again after.”

But according to Nishiura, despite all stops and starts, kendo is for life.

“It’s a lifelong learning experience,” Nishiura says. “There isn’t any endpoint to kendo training, so everybody at any stage are beginners. At the same time, they are experienced.… We don’t know exactly where we are in the cycle.”

Despite the spiritual equality, kendoka ranks are taken seriously in the dojo. At the end of each practice, the men and women form two lines: one of senseis and one of students.

“Respect’s a big part,” Minaki says. “You bow to the front … you pay respects to be able use the facility. You bow to … everyone you practiced with. … Then you bow to your senseis.”

As students begin to form a separate line in front of the senseis to receive comments on their performance, Minaki breaks away to kneel behind Nishiura. He quietly takes Nishiura’s protective armor and begins to fold it.

“That’s just common,” Minaki says. “The younger people in the dojo tend to do it for the more respected.”

According to Nishiura, Minaki has shown great promise, both in sparring skill and kendo character.

“He’s a good kid,” Nishiura says. “I think he will be a very useful person for society.”