Warning: This feature deals with accounts of sexual assault and may be a trigger for some readers.

Editor’s Note: While we recognize the sensitive nature of this piece, we believe that stories like this are paramount in destigmatizing conversation surrounding sexual assault and misconduct, especially in light of recent local and national events. To ensure our reporting was as accurate and compassionate as possible, all three writers took a self-directed “Reporting Sexual Violence” course provided by the Poynter Institute. In addition, the following content has been approved by the survivors and sources who shared their stories. Finally, we would like to thank the Student Press Law Center for their guidance throughout this process and for reviewing a substantive draft of the article prior to publication.

There was a deafening silence in the small, upstairs room of the Capitol Building as Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified before a Senate committee accusing then Supreme Court-nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her in high school. As she spoke, Palo Alto High School alumnus Jay Backstrand (Class of 1986) sat on the edge of his seat behind her — stoic, but riveted.

Backstrand, who met Ford through their sons’ mutual love for sports — he coached her son’s baseball team and their sons play basketball together — was invited to Washington, D.C., along with Ford’s family and friends, to support her through the process.

According to Backstrand, while sexual assaults must have occurred during high school in the ’80s, there was little conversation about it. Backstrand believes it is this taboo that made what Ford did so impactful.

“The important thing about what Christine did was that she made it more the norm that if something happens, you come forward,” he says.

Although Ford’s testimony has sparked more nationwide dialogue, the stigma surrounding sexual violence when Ford was in high school in the ’80s stifled assault victims from speaking out and limited the resources provided to them. Today, despite increased conversation about sexual assault and consent, many survivors still fear societal backlash.

In this story, Verde explores the evolving culture of sexual assault, examining the experiences of Paly students from the ’80s and today. Jerry Scher, Paly (Class of 1981), describes the party culture in the 1980s. Anna, a pseudonym for a former Paly student from the ’80s, shares her experience with sexual assault and sheds light on the victim-blaming culture. A current Paly student, Kate — whose name has also been changed to protect her identity— reveals the continuance of sexual assault in our community.

The ’80s

According to Scher, there were parties thrown every weekend that were attended by everyone from straight-A students to football players. Although he believes incidents of sexual assault must have occurred at these parties, Scher doesn’t recall hearing any accounts of it.

“I never heard of anything that I would term ‘violent,’” Scher says. “It [partying] was just people having a good time.”

Hearing Ford’s testimony, however, Anna was reminded of her own high school experiences with sexual assault in the ’80s.

“It was like having a flashback and I could imagine the terror that she was feeling,” Anna says. “I just felt for her because I felt like she was being put on trial and it’s not something you would make up. It’s really a shameful feeling and to share it with the world like that is pretty courageous.”

Nearly 3,000 miles across the country in Palo Alto around the same time as Ford’s sexual assault, Anna was raped in a park by her boyfriend at the time.

“His [her boyfriend’s] friend held me down and my boyfriend raped me.” Recounting the act years later, each word Anna speaks is uttered slowly, with precision. “My friends that were there didn’t do anything about it. … That was my first experience [with sexual assault].”

Anna, who attended Paly until her sophomore year, says sexual misconduct was a common occurrence. She didn’t know many friends who hadn’t experienced some form of sexual violence, which ranged from harassment to assault. As a high schooler, she says she was raped twice, both times by boys she knew and trusted.

After word spread of her rape at the park, her close friends started shunning her then-boyfriend and leaving him out of certain social gatherings. But that, Anna says, was the extent of his punishment — she suffered far worse damage to her reputation and mental health.

“After that, they [classmates] started bullying me,” Anna says. “At school, word got around, and then I got a reputation for being a slut. It really affected my attitude toward school and I just kind of stopped going.”

With the exception of a few close friends, Anna says no one at school who had heard about the rape reached out to her, offered support or encouraged her to report the incident to the police.

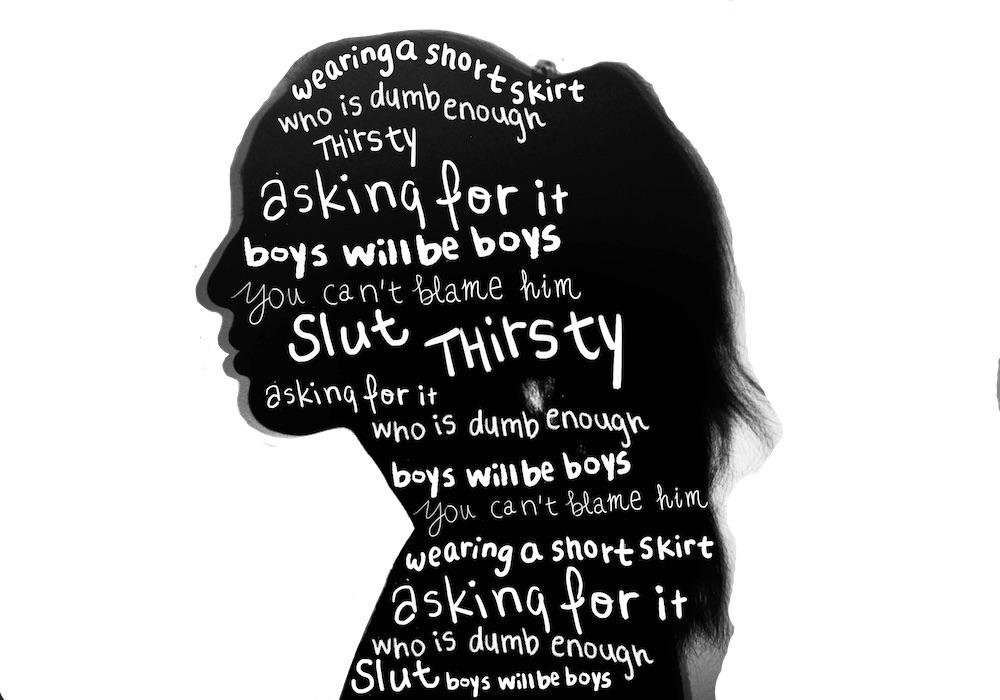

“If you let it happen, you must be a slut — that was how everybody else looked at it,” Anna says. “You put yourself in that situation so it’s your own fault.”

According to Anna, the victim-blaming culture often neglected to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions.

“It was ‘Boys will be boys’ and ‘You’re wearing a short skirt’ so she was asking for it,” Anna says. “The victim [was] the first person they would turn and look at and see if they’re to blame.”

Although Anna says she recognized the gravity of what had been done to her, feelings of shame and fear stopped her from reporting the first assault.

“I was afraid they [the police] wouldn’t believe me,” Anna says, “Because I had already acquired the reputation of being a slut, so they would just blow it off.”

Anna says she also could not receive support from her parents, who were absent during this time.

“I was an emancipated minor and I didn’t know what my rights were,” Anna says, pausing to steady her voice. “I needed help but I had no one to turn to.”

While Anna and Scher differed in their party experiences, they agree on this: There was barely any conversation about consent and sexual assault in the ’80s.

“No one knew about ‘no’ [or] ‘stop’; that just wasn’t a concept back then,” Scher says. “There were definitely no teachers talking about consent … It was a different time.”

Likewise, Anna describes a campus culture with no conversation about consent, assault or healthy relationships.

“It [consent] was not talked about,” Anna says. “Health class was about reproduction, not about relationships.”

Kate’s story

Three decades later, Kate’s story is jarringly similar to Anna’s and Ford’s.

Kate, too, was assaulted at a house party when she was in high school. Though she came with a group of friends, she lost them in the chaos of the party, and while searching for her friends, came across a boy from a neighboring high school with whom she had become acquainted through mutual friends.

By midnight they were both inebriated. He was mildly drunk after a couple of beers, she says, but shots of vodka combined with a lower tolerance for alcohol left her stumbling and slurring her speech — far past the point of consent — when he propositioned her. He seemed to accept her refusal to have sex with him, she says, but later asked her if she wanted to “just make out.”

“I was like ‘sure’ even though I didn’t really want to because I felt bad that I said no to having sex with him,” Kate says.

“It was like I couldn’t remember how to scream”

– Kate, assault victim

According to Kate, they went upstairs together and it was then that he began groping her. Though she does not recall exactly what happened, she remembers him removing her top, despite her repeated efforts to stop him.

“I really wanted to scream at him or for help,” she says, stopping to wipe away tears. “But I just kind of froze, and maybe it was the alcohol or being scared, but it was like I couldn’t remember how to scream.”

She remembers going limp, incapacitated by a feeling of helplessness. The events were hazy after that — the next thing she clearly remembers is waking up, alone, without her shirt. In the following days, she struggled to process what happened.

When she was finally able to organize her thoughts, she says, she made the decision not to report what had happened. According to Kate, she confided in the girls who came to the party with her, but despite their initial displays of shock and sympathy at her story, a friend sent her screenshots of text messages they had sent to each other about her. They labeled her foolish for allowing herself to be led upstairs and excused the boy’s actions, saying Kate had always acted “thirsty” — desperate for male attention.

After seeing how her friends responded, Kate says, she was shocked and confused.

“I couldn’t tell my parents and stopped talking to my friends after seeing what they said,” she says. “So I honestly just had

no one to turn to. Even two years later, there are still times I relive parts of it and just start randomly sobbing.”

She is nevertheless healing, she says, and finding ways to cope with the trauma of the events. Though she is learning not to blame herself for the assault, she has one regret: “If I could do it all over again I would never have gone to that party,” she says.

Conversation about consent

As demonstrated by the experiences of Ford, Anna and Kate, sexual assault has occurred in high schools across the country for decades and continues to be a difficult issue to combat.

“What really perpetuates the culture of sexual assault is this concept of victim-blaming and people making excuses for attackers,” Kate stated in a text.

However, there is an increasingly open conservation about rape culture, education for teenagers of

all gender identities on the legality of consent and ramifications of sexual assault and valuable resources for survivors to move forward after such a traumatic event.

While Anna felt she had no one to turn to and lacked knowledge of her rights, communities now have counselors and professionals to help and encourage survivors to come forward with allegations. Yet, as Kate’s story illustrates, the culture of “boys will be boys” prevails and the practice of victim-blaming is still firmly rooted in our society.

“Society as a whole needs to understand that their son or brother or boyfriend or whatever’s ‘one mistake’ is the reason that my life will never be the same…” Kate stated. “My body, happiness, and agency is not yours to f–king violate in the name of being young and making mistakes.” v

Survivors of sexual assault are urged to call Mountain View Planned Parenthood at 1-650-948-0807, the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-4673 or text HELLO to 741741 to speak to a counselor in real-time.