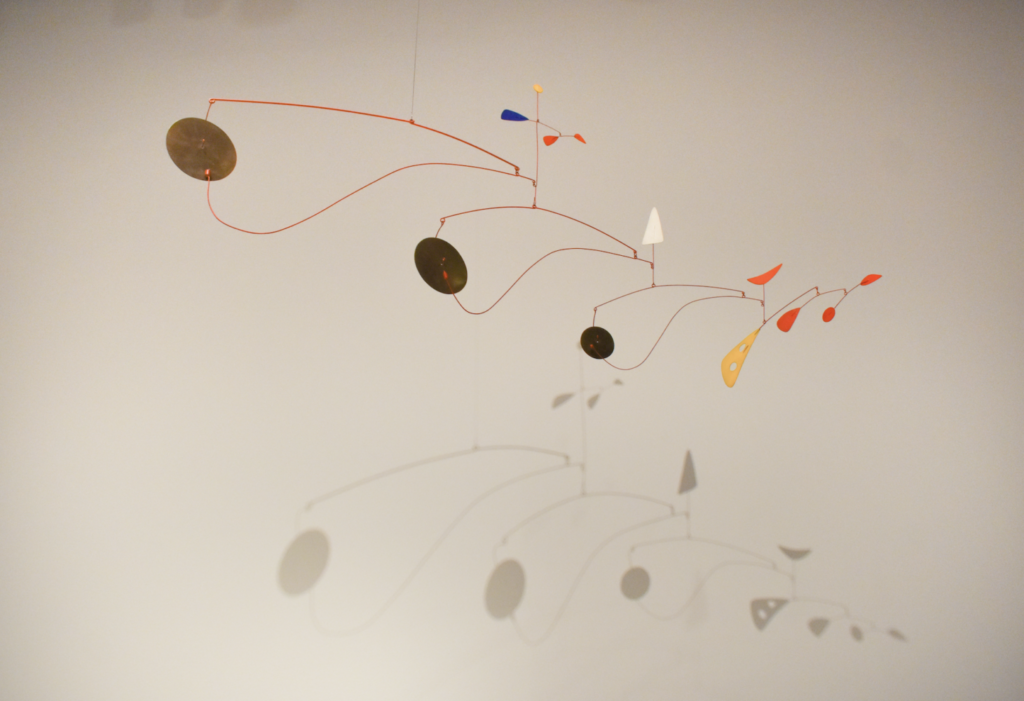

Intricate shadows — an acrobat, a solar system, a side profile — cloak the walls, swaying with the sea of people moving from one nameplate to the next. Primary colors decorate canvas and sheet metal, striking eyes all the way across the pale white room. Memories live in wooden frames, immortalizing every interaction between two illustrious 20th century artists.

As COVID-19 cases in California decline, museums across the Bay Area are slowly welcoming the public back into carefully curated art galleries and exhibitions. For the de Young Museum of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco located in Golden Gate Park, this means premiering exhibits that have been years in the making, including “Calder-Picasso,” “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving” and “Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI.”

Among dozens of new galleries, “Calder-Picasso” is a standout collection. The featured works juxtapose two legendary artists of the 20th century — Alexander Calder and Pablo Picasso.

According to Palo Alto High School AP Art History teacher Sue La Fetra, Picasso’s work was described as deconstructionist — breaking down a scene to its fundamentals — while Calder’s work took a more constructionist angle. Despite their differences in style, the two artists often paralleled each other in subject matter.

“The exhibition focuses on the two artists’ shared fascination with exploring and expanding the potential of some of the most fundamental components of art — the line, the volume, the void, and gravity,” coordinating curator of “Calder-Picasso” Timothy Anglin Burgard said.

Legacies left behind

Decades after the distinctly unique artists took the world by storm, the influence of Calder and Picasso can still be found in museums today.

Calder was an American sculptor known for his innovative kinetic art and public sculptures. The most notable pieces from his career include his bold, wind-powered constructions, which came to be known as “mobiles” — the French word for motion. Calder filled spaces with clear purpose and an array of materials, from sheet metal and wire to wheels and string.

“He really loved making things and the idea of looking at abstracted forms, and how you can use lots of the negative space,” La Fetra said.

“Artists and their art also can transcend the time and place of their creation and speak to the present — and to the future.”

— Timothy Anglin Burgard, curator

Picasso was an Spanish painter, sculptor, ceramicist and co-founder of the Cubism movement. Picasso’s work is characterized by new ideas of the time, such as Sigmund Freud’s theory of the subconscious and Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. Picasso began to abstract his work more and more in order to impact the subconscious mind of the viewer.

“You have the abstraction of forms to the point where it doesn’t really represent anything but art,” La Fetra said. “It is art.”

An exemplary experience

The de Young crafts an excellent exposition of the two artists’ work. Throughout the exhibit, we see both Calder and Picasso work through different mediums and styles, moving from wire structures and sketches to abstract paintings and mobiles. On top of being a tactful comparison of the two artists, it is also a visual history lesson. As Calder and Picasso’s paths cross, we see the reflection of shared ideas through the art as the two employ similar colors and shapes to communicate a specific emotion.

Picasso’s paintings, while not as physically dynamic as Calder’s pieces, are animated through their strategic placement alongside the mobiles. The overlapping elements across two artworks meld the pieces into one, giving Picasso’s paintings the liveliness and reality of a mobile while transforming the rigidity of Calder’s structures into something much more fluid.

The mobiles are purposefully hung and lit from angles that incorporate highlights and shadows into the artwork — pushing the viewer to examine art beyond the tangible object. The shadows create a sense of permanence and a connection to a multidimensional reality that would otherwise be unachievable in the canvas format.

Calder’s “Vertical Foliage” is especially impressive. The massive wire sculpture resembles leaves on a branch, with each wire extending outward to carry a painted piece of sheet metal.

The mobile seems to be an ode to nature, and the peace that can be found within. Each slight movement of the mobile creates a sense of anticipation that braces the viewer for something beyond the sculpture. The expectation of something dramatic, like a sudden loss of balance, leaves us with the stoic reality of the immovable piece.

In Picasso’s oil painting “Nu couche (Reclining Nude),” he depicts a lover through thick black outlines and dramatic strokes of color, echoing Calder’s imaginative wire sculptures that prompt viewers to interpret a subject for themselves. With fruits and leaves shaping the woman’s curves, the viewer takes on an earthly, celestial perspective.

In a period of incredible turmoil, the shared experiences of artists can shed light on the value of expression through time.

“Artists and their art also can transcend the time and place of their creation and speak to the present — and to the future,” Burgard wrote. “While it is true that visual vocabularies can go in and out of style, the fundamental components of art, including humanity, the human condition, and the desire to create and express something unique and meaningful, never lose their relevance.”