“If you took a minute of silence for each [person who died of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome since the beginning of the 80s epidemic], we’d have the equivalent of 66 years of silence,” says Vince Crisostomo, a program manager at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. “The thing about this [AIDS] is that … we had the tools to prevent infection, but not the political will. Knowing [about] those 35 million people, I feel like we owe it to them to stand up. Those of us still here have an obligation to stand up for the next chapter.”

In the Bay Area, the history of the AIDS epidemic lives and breathes in our healthcare systems, our schools and most prominently, the minds of those who witnessed the suffering of thousands. Many remember how, during a time of fear and uncertainty, the government failed to react until at least 19,000 people in the United States had died from a disease wrongly identified by popular culture as “gay cancer,” a disease about which the country’s populace knew almost nothing.

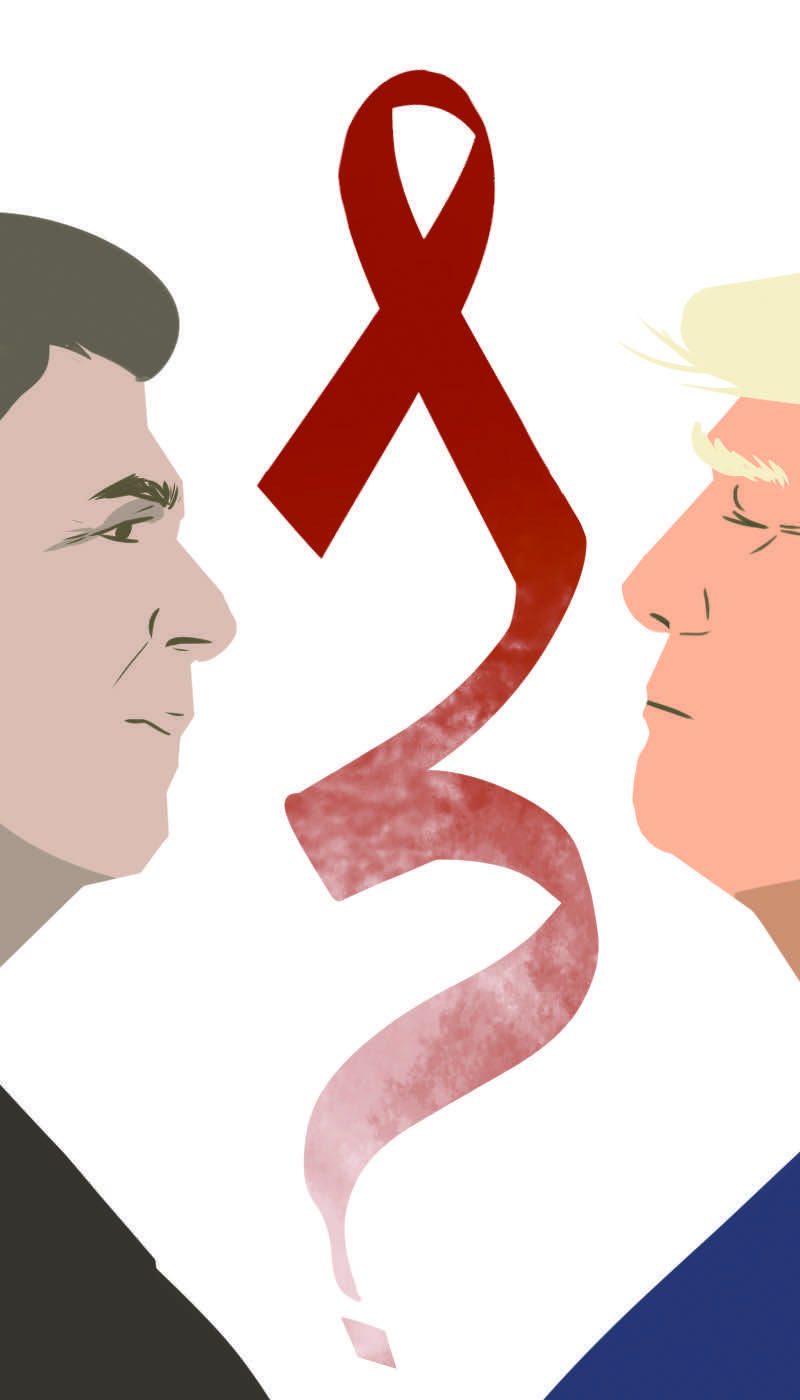

With a conservative, “alt-right” presidential administration coming into power three and a half decades after the start of the AIDS crisis, some concerned individuals apprehensively wonder how another epidemic such as AIDS, one that primarily targets a minority community, would be addressed by our national government. Looking towards our future, we are forced to reflect upon our past.

“There is a conservative constituency in our country who is very anti-gay,” Crisostomo says. “Almost everything this whole administration has done has been challenging for our [LGBT] community. I think it [the HIV/AIDS epidemic] is going to be the greatest teacher of all time.”

Where It Started

The AIDS epidemic began with a few cases of an immune deficiency disease, usually associated with immunosuppressive drugs or drugs that weaken the immune system during cancer treatments, in San Francisco. Although the disease grew rapidly during the early 80s, there was no diagnosis for AIDS or even HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus which causes AIDS. However, one fact known for certain was that the gay community was disproportionately affected by the illness because of the ease with which the virus could be transmitted during anal sex. At the time, gay men were subject to ridicule and discrimination and were often told that they were responsible for their ill fortune.

San Francisco. Although the disease grew rapidly during the early 80s, there was no diagnosis for AIDS or even HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus which causes AIDS. However, one fact known for certain was that the gay community was disproportionately affected by the illness because of the ease with which the virus could be transmitted during anal sex. At the time, gay men were subject to ridicule and discrimination and were often told that they were responsible for their ill fortune.

“At some point at that time [the 80s] it was said that AIDS was a gay community issue, not everybody’s issue,” says 48-year-old Albert Sandoval, a gay man who lived in San Francisco during the epidemic. “I guess the gays were also pinned that title because the straight community always says that it was our fault. We were the ones who were promiscuous and didn’t care enough. That was kind of the message from a big section of the community here [in San Francisco].”

Such homophobia was not limited to radical individuals — it seeped into legislature in the form of Helm’s Amendments, which barred the federal funding of any educational materials that intended to “promote or encourage, directly or indirectly, homosexual sexual activity.” The intended effect of these rules was to discourage gay sexual activity, but in reality, the lack of support for the AIDS-affected community kept solutions for the epidemic at bay.

When all major, federal sources of support seemed to ignore the ever-growing epidemic, the gay community came together.

“Gay men banded together,” says Philip Pizzo, former dean of the medical school at Stanford University. “They simply did not accept the fact that there would not be effective treatments. They organized, they pushed the medical community, they pushed the regulatory community, the Food and Drug Administration, they pushed the NIH [National Institutes of Health] to say ‘You have to develop things’ and it had an effect.”

Click on this photo for a story about media censorship during the AIDS epidemic

Let’s Talk About AIDS

In response to the gay community’s action, many organizations designed awareness campaigns to combat these homophobic sentiments and to deconstruct the misconceptions surrounding HIV and AIDS.

Yet the awareness induced by these campaigns was not enough to spur conversation. Even in liberal communities like Palo Alto, AIDS was discounted and failed to be discussed in schools like Palo Alto High School, according to math teacher Arne Lim, who began teaching at Paly in 1985.

“The awareness of something like this was slow,” Lim says. “It was slow because it was hard for people to believe that it was actually happening. We [Paly teachers] weren’t told to discuss it [AIDS]. We weren’t told not to discuss it , but we weren’t told ‘This is what you need to say.’”

, but we weren’t told ‘This is what you need to say.’”

This lack of discourse about AIDS was representative of the mystery shrouding the disease. Community members failed to comprehend how it was transmitted or even how it spread beyond the gay community, allowing unsafe practices to persist and discrimination of AIDS affected individuals to continue.

“One of my clients told me ages ago, they didn’t fear the disease, getting sick and dying, they feared people and what people would do to them,” Crisostomo says. “People with closed minds don’t help. It’s one of the challenges. I long for the day when the quality of life and human life of my clients is not dependent on who’s in office, not dependent on who has more money.”

After years of silent, distressed suffering, AIDS patients finally began feeling support from the community during the late 80s. As education spread and the disease began to be taken seriously, the community eventually came to the understanding that HIV, and consequently AIDS, could affect anyone regardless of sexual orientation.

“I long for the day when the quality of life and human life of my clients is not dependent on who’s in office, not dependent on who has more money.”

-Vince Crisostomo, San Francisco AIDS Foundation

An Enduring Lesson

According to Pizzo, the experience of an incredibly debilitating disease such as AIDS is shaped by the surrounding community that supports the individual. As demonstrated during the AIDS epidemic, when the government fails to support a minority group and educate the general populace in times of distress, communities across the country falter in supporting the affected minority. In our current political scene, as the targeting of minority groups is increasingly prevalent, the government’s involvement has become increasingly crucial, according to Crisostomo.

“There’s a lot of fear mongering and they [the Trump administration] also create situations where people don’t make the best decisions,” Crisostomo says. “The ban on immigration was highly discriminatory. Any time you can discriminate against one group of people, nobody is safe.”

Where we once saw laws preventing AIDS education, we now see the government threatening to withhold funding from crucial, modern sources of medical information.

“They’re also defunding Planned Parenthood,” Crisostomo says. “You wouldn’t think that’s relevant to our cause [AIDS], but in some states, that’s where people get their education and learn of HIV.”

Further, President Trump, according to multiple of his statements, strongly opposes vaccines, a method scientifically proven to reduce disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control. To Crisostomo, Trump’s disregard of evidence in favor of crucial health measures is another way that our country has failed to learn from past mistakes and part of the lasting shame assigned to HIV and AIDS. Although it’s been years since the height of the epide mic, Crisostomo feels that society continues to look at the gay community with prejudice, especially in the context of the new administration.

mic, Crisostomo feels that society continues to look at the gay community with prejudice, especially in the context of the new administration.

“There’s a lot of stigma about being gay; we’ve managed to address a lot of that but it’s still present,” Crisostomo says. “There’s criminalization in California and other states. There is a conservative constituency in our country who are very anti-gay, anti-HIV, anti-a lot of things.”

Yet Pizzo, who views the issue from a more scientific perspective, believes that both society and medicine have made great strides in combating the disease.

“It’s not where it started,” Pizzo says. “It started with fear, blaming, stigmatization, frustration, anger — but it ultimately galvanized the set of approaches that really led to tremendous progress. It’s a very good example of how fear can dominate a reality, create judgements that are not appropriate, things that we’re dealing with once again in different sphere of our life.”

Though Pizzo and Crisostomo experienced the HIV/AIDS epedemic in dissimilar ways, both agree on the persisting relevance of that period in history. In Crisostomo’s mind, the trauma that AIDS patients endured is everlasting, and the mental health of those individuals is still influenced by the apathetic response to their struggle. He believes that society owes it to the millions of people who suffered at the hands of apathy to take a stance on current day controversial issues and to inspire change.

“Maybe you don’t want to educate your whole community, but you can educate a family member and at least engage with them,” Crisostomo says. “We had this thing: silence equals death. To me, that’s still true in a lot of ways. The first time it happens it’s understandable because you maybe don’t know what to do, but hopefully it wakes you up, next time you’ll be better prepared.”