Amy Watt holds her starting block — a homemade apparatus composed of a hollowed out tennis ball can secured onto a two by four block of wood with a generous amount of duck tape. It willingly supports her, bearing her weight as she takes her place on the starting blocks, doing the job as well as a manufactured prosthetic limb could manage. As she tells the story of this simple contraption, one that enables her to shave precious seconds off her time in the 400m, her quiet determination to become an elite runner shines through.

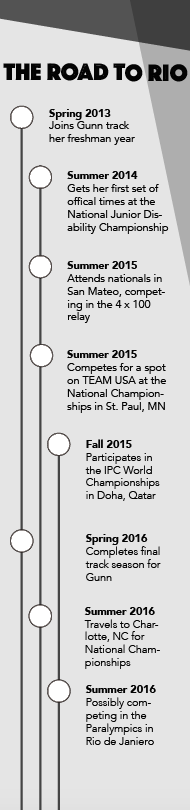

In the span of less than two years, Watt, a senior at Gunn High School, has gone from a spectator of Paralympic athletics to a competitor at the highest level, having raced at the Paralympic World Championships in Doha, Qatar, this October. She regularly competes in track and field along with able-bodied athletes for Gunn, alternating between hurdles, long jump and sprints in an effort to help her team accumulate points during each meet. Regardless of the competition she encounters, Watt seems unfazed, and has a willingness to smoothly adapt to any condition.

Watt was born without her left forearm, a birth defect called meromelia. Despite being a congenital amputee by birth, Watt has always been naturally athletic and started playing soccer for Stanford Soccer Club at a young age. In middle school, she joined the track team and discovered a passion for running.

With her spikes, homemade starting block and her ability to remain unfazed regardless of the competition or challenges she faces, Watt has the potential to continue her ascent to the upper reaches of Paralympic athletics.

Natural Beginnings

Watt’s first experience at a Paralympic championship began in the stands and ended on the rubber. She began that day in spring 2014 up in the bleachers dressed in her casual Saturday attire of a T-shirt and shorts, only in San Mateo to cheer on her friend from summer camp who journeyed all the way from Iowa to compete at the national trials.

Watt had only decided to come to the event the day before, when former Paralympian Ranjit Steiner bumped into her on the Gunn track, noticed her arm and invited her to the competition the next day.

As she glanced out onto the track, Watt remembers her friend yelling out to her. The relay team was short a runner, and they wanted her to run the third leg for them. Watt threw on a pair of running pants and borrowed a shirt; then three-time Paralympian April Holmes helped complete her outfit by handing her a pair of her running shoes.

Her relay team ended up setting a Paralympic national record, running a time of 56.69 seconds. This year, her team ran the same relay again with a time of 53.90 seconds. With a time that was pending for a world record, Watt put herself in contention for representing Team USA internationally.

To confirm her eligibility, Watt needed to get classified as an amputee, a process in which the International Paralympic Committee determines what class an athlete will compete in. After the whirlwind 30-day classification process, Watt was set to test herself in the IPC World Championship Trials.

Launch into Community

Watt has inherently been part of the amputee community since the day she was born. In the summer of 2008, her mother signed her up for the Amputee Coalition of America’s Paddy Rossbach Youth Camp, a camp made exclusively for teen amputees that aims to encourage them to step out of their comfort zones. Over the years, the camp has become a place of comfort for Watt, but even more for other amputees who have been recipients of bullying having grown up elsewhere.

While Watt feels that the Palo Alto community was an accepting one to grow up in, many of the amputees she met at camp been the recipients of bullying elsewhere.

“Definitely for them [other camp attendees] it was a big thing for them to have a large group of people who were just like them,” she says. “It was a nice place for me to go and meet new people.”

“There was a guy who said, ‘Can I lend a hand?’ and then they [an amputee] would say, ‘No, but I have a leg’ and then they brought out their prosthetic,” Watt says.

Through the camp’s activities of rock climbing and a ropes course, Watt created and maintained friendships with her fellow camp attendees, who she can easily relate and connect with.

“There’s people I’ve met where I’ve only known them for a total of four weeks and I feel like I’ve known them for so long,” she says.

In the years that followed, Watt has been eager to return to the welcoming nature of the camp each summer. Much like the acceptance from the amputee community, Watt’s surge from Gunn’s track community into the international sphere came with an unexpected welcome from the Paralympic group.

Part of this acceptance is a solidarity in knowing and being able to gauge each other’s comfort levels as they all share a tacit understanding about letting others be independent. Watt recalls that despite routinely maintaining that she does not need help, the waiters at the World Championships insisted they carry her plates after dinner. Watt’s assertions often match those of the disabled and Paralympic athletic community who willingly offer help when they recognize it’s needed while allowing each other to still maintain independence.

“I don’t go out of my way to help [a Paralympic athlete] because I know that’s not something I would want,” Watt says. “People definitely try to offer help because we look like we need help, but since we’ve been living with our disabilities for our whole lives, we don’t feel like we need help.”

Training for Doha

As she got set in the starting blocks, preparing to fight for a spot in the IPC World Championship, Watt recalls balancing on her right hand, and bursting out of the starting blocks, quickly gaining a significant lead over her competitors.

The 400 is a furious race, an elongated sprint of two turns and two straightaways all lasting just over a minute. Yet in this instance, as she rounded the final turn, she remembers her mind stopping to pause as she saw the number 58 flash up on the screen.

“I knew the qualifying time [for the Paralympics] was 65 seconds, and in that moment I thought, ‘I can actually do this,’” Watt says. She felt herself surge forward securing her place in the IPC World Championships, along with a personal record time.

Yet her preparation was not over. With the high school track season ending in May, and the IPC World Championships not taking place until October, Watt needed to maintain her form and fitness. For her coach, Joy Upshaw, training Watt was different than preparing many athletes over the years for Gunn. Strong in the 400m, 200m, 100m and the long jump, by training for all four events, Watt risked exhaustion and burnout. After the conclusion of the high school track season, Upshaw began to work individually with Watt, setting specific goals, pulling from her years of attending high performance seminars and experience.

“We worked on her speed off the front end,” Upshaw says, referring to the acceleration needed in both the sprints and jumps.

Yet perfecting her technique was only half the task at hand; if she was to succeed in her events Doha, she would need to bring her “grit” to the next level. Watt’s longtime friend and Gunn track teammate Maya Miklos  describes “grit” as the feeling when lactic acid gushes through and screams at a runner’s thighs as they round the final turn of a race. The ability to bite down on the bullet, and push through the final 100 meters, Miklos says, can only be achieved through training. Miklos too was competing on a national level this summer, placing 10th in California for the 300m hurdles, and trained with Watt regularly.

describes “grit” as the feeling when lactic acid gushes through and screams at a runner’s thighs as they round the final turn of a race. The ability to bite down on the bullet, and push through the final 100 meters, Miklos says, can only be achieved through training. Miklos too was competing on a national level this summer, placing 10th in California for the 300m hurdles, and trained with Watt regularly.

“The difficulty of our workouts is what helps us build that mental strength,” Miklos says. “You have to really want it.” Miklos’ speed out of the blocks pushes Watt onward, an integral part in ensuring she maximize

s her potential.

So while her classmates competed in Homecoming week festivities in October, Watt was lining up against the world’s best, trying to establish herself among more experienced competitors. Based in a tourist hotel rather than an athletes village, Watt crammed in her homework between events, in order to clear her mind when it came time to race.

The professionalism at the elite stage was a noticeable difference for Watt, and it highlighted her relative inexperience at that level.

“We were brought to a check in tent about 30 minutes before our race,” Watt says. “Here they checked ou

r shoes, and we warmed up, up until the timing of the race.”

The additional build up time only added to the jitters and nerves she felt at the time, yet she discovered that the paralympic community is one that fostersdevelopment along with competition.

Road to Rio and Beyond

A normal high school track season lasts until May, occasionally June. It’s now October and with her flight back from Doha, Watt’s season is finally over. She’s eager to put her feet up and rest for a while. While she hopes to continue competing at the top for years to come, Watt also aspires to become a veterinarian, combining her love for animals with her passion for science. She volunteers with the Nine Lives Foundation and the Doggie Protective Services, a canine rescue group that brings dogs in high kill shelters to the Bay Area and hosts adoption events.

Yet there is a quiet determination about her that just won’t lie down. She dreams of boarding the plane with Team USA next summer to Rio de Janeiro, to take part in the largest Paralympic event in the world — the Paralympics — featuring over 4,350 athletes from 179 countries.

In Rio, there lies a bit of unfinished business. This past October, a competitor from Australia who she had befriended asked her by text to swap shirts. Watt, however, was already on the plane heading home from Doha, missed out on the opportunity to make the gesture of respect and compassion.

“If we both make it to Rio next summer, I promised her that we will finally get to trade shirts.”