“I did what I had to do,” says Jake, a former high school athlete whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

Six days a week, every week, for four years, Jake spent hours at practice, pushing his body to its limits. When he wasn’t practicing, he used the time to study in order to maintain a stellar academic record, one Jake says far surpassed that of his more athletically-gifted peers. But when it came time for college recruitment, Jake found that, despite his dedication and grueling schedule, he had come up short. In a moment of desperation, he says, he submitted a falsified athletic profile to coaches during the college recruitment process his senior year of high school.

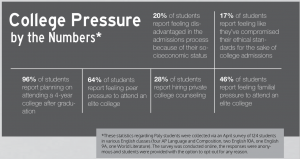

Jake was just one of the many Bay Area teenagers caught up in the competition of elite college admissions. As many local students set elite college attendance as a personal necessity, the number of applications to such institutions has continued to rise, tightening competition and lowering admissions rates. During this past application cycle, for example, the admissions rates of Yale University, the University of Southern California and the University of California, Berkeley hit record lows.

Meanwhile, building a qualified applicant profile grows increasingly complex. In addition to rising standardized test scores, a well-prepared candidate is often more than academically strong. According to the College Board, under “holistic admissions” practices, materials such as extracurricular lists, essays and letters of recommendation also determine an applicant’s leadership qualities and intellectual curiosity, among other criteria. But as exemplified in the March college admissions scandal — known as Operation Varsity Blues — the intensifying competition can lead hopeful students and parents to turn to bribes instead of books.

Of the 33 parents who have been charged in the scandal, 13 hail from the Bay Area and two are Palo Alto High School parents, according to the official affidavit from the Department of Justice — a jarring catalog of the wealth, privilege and culture of elite college admissions nationwide and locally. In this story, Verde explores the implications of the increasing pressure surrounding elite college admissions on Paly’s campus.

Cutthroat competition

According to Allison Wu (Class of 2018), a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania, the emphasis on attending an elite college is a dominant — and stressful — presence at Paly. Wu describes it as “ingrained in the culture,” so much so that even in retrospect, she admits she would have “still [wanted] to go to one [an elite school]” despite now acknowledging that colleges provide “comparable” educational experiences regardless of rank.

“At Paly, the end goal is to go to an elite college or to go to college,” she says. “We have the college map from Campy [The Campanile newspaper], we have college day [May 1], you put the college on your [graduation] cap.”

While college-centric traditions perpetuate this emphasis, Wu also points to the status associated with attending an elite college as a contributing factor.

“It definitely should not create superiority or a sense of superiority, and it does,” Wu says. “I saw that a lot, I think.”

As a longtime teacher advisor and history teacher, Adam Yonkers shares Wu’s belief that, in Paly’s high pressure environment, humility and sensitivity to the feelings of others in the admissions process should be prioritized.

“I hesitate with my students to make it [their college admission] super exciting because there might be someone across the room thinking ‘Oh, I got denied,’” Yonkers says.

According to senior Nicholas Padmanabhan, it is the normalization of elite college attendance which fuels this culture.

“The historical precedent of that [elite college acceptances] creates a really competitive atmosphere,” Padmanabhan says. “We’re in a bubble — it’s not the norm.”

The context of the surrounding Palo Alto community also explains why many students not only pursue an elite higher education but expect access to one, says junior Harriet Baldwin.

“Palo Alto, in general, is definitely [a] very affluent community,” Baldwin says. “Since you [Paly students] have grown up in this place of privilege … you assume that you will continue that in college and that you’ll get into these top-rated schools.”

“Since you [Paly students] have grown up in this place of privilege … you assume that you will continue that in college and that you’ll get into these top-rated schools.”

— Harriet Baldwin, junior

Wu says it is this obsession over elite universities that often leads students to make academic decisions for the sake of improving their admissions prospects and not exploring a genuine interest.

“People take honors classes and AP [Advanced Placement] classes because they think it’ll increase their chances of getting into a better school,” Wu says. “I don’t think people learn for the passion of actually learning the material, but for what it’ll look like on their college application.”

Pressure for perfection

While many students challenge themselves and engage in activities for the sake of gaining admission to elite colleges, some take it a step further — crossing the murky line between simply boosting admissions qualifications and blatant unethicality. For Jake, straddling that line was a delicate but fruitful endeavor.

Jake, who currently attends an Ivy League institution, says he was a dedicated athlete and diligent student, but was simply not physically gifted enough for recruitment. Although he set his sights on recruitment to elite institutions, when the recruiting process began junior year, their coaches were not contacting him. A sense of desperation set in, and he adopted an intense training regimen — but to no avail. Then, his anxiety reached a fever pitch.

“Maybe I overworked myself or anxiety, but I never got the results [I needed],” Jake says. “By October, when people were committing, I pretty much just reached my peak and snapped.”

Though Jake acknowledges what he did was wrong, he says he feels that his actions were, in some sense, justified by his hard work — unlike the kind of cheating that allegedly occurred in the Operation Varsity Blues scandal by parents such as actress Lori Loughlin, whose daughters were both fraudulently recruited at USC.

“Not excusing what I did, but I don’t think it’s the same level of cheating as those parents [involved in the scandal] or what Aunt Becky [Loughlin] did with her daughters,” he says.

Like many parents involved in the scandal, Jake says, his placed a significant amount of pressure on him, which, combined with his own desire for success, led to his decision to lie about his score.

“I have actual goals and ambition,” Jake says. “I did what I had to do.”

Furthermore, Jake says he sees little disparity between his actions and other more common means of admission.

“I just don’t see how what I did is that different … from legacy kids automatically getting into these amazing colleges or paying a [lot] for test prep and college counseling,” he says. “You use the resources you have to give yourself an edge in the competition and that’s what I did.”

Fuel to the fire

For those without the advantage of athletic recruitment, Wu says she believes her peers engaged in extracurriculars and pandered to their teacher advisors, who write a summative letter of recommendation to colleges, for the same purpose. This competitive drive not only intensified an already stressful process but also led to interpersonal strains, she says.

“There’s that lingering tension between you and your classmates or you and the people who applied to the same school,” Wu says. “You think that they’re going to ‘take your spot’ at that school when it doesn’t actually work that way.”

According to Yonkers, it is this practice of searching for a perfect algorithm for getting into college that contributes to Paly’s pressure-cooker atmosphere.

“Everyone is looking for that secret sauce — what it is that gets you into a school,” Yonkers says. “There’s this notion with Paly students that they’re competing for a limited number of spots at colleges which causes this culture of sabotage and cannibalism.”

While the intense and competitive nature of Paly’s admissions culture is stifling to some, for others, like senior Gerzain Gutierrez, it can be life-changing.

While the intense and competitive nature of Paly’s admissions culture is stifling to some, for others, like senior Gerzain Gutierrez, it can be life-changing.

Gutierrez is one of only a few members of his family living in the U.S. and will be the first to attend college — he is off to Stanford University in the fall. Most of his family lives in Mexico and entered the workforce directly after high school, a path that Gutierrez himself always thought he would follow.

“When I was little I thought that was what I would do — just go to work after school because that’s just what people in my family did,” Gutierrez says.

After starting high school at Paly, however, Gutierrez says it was the high-achieving, college-obsessed atmosphere that made the once abstract prospect of higher education a reality.

“When I started my freshman year, everyone was already talking about college,” Gutierrez says. “I feel like … people are frowned upon if they don’t go to college after Paly, which definitely pushed me to work harder and think about going to college because I never thought I would when I was little.”

“We shouldn’t be focusing on comparing ourselves to others, rather than finding on [college] that fits for us.”

— Evan Baldonado, senior

Pay to play

But while Gutierrez shared the ambitions of his college-oriented peers, the costly college prep resources many of them were able to utilize were neither practical nor realistic for him.

“My mom just couldn’t afford it [private college counseling and test prep],” Gutierrez says. “I used Khan Academy for the SAT … but I felt like if I’d had a tutor, maybe I could have gotten a higher score.”

Outside of standardized testing, however, Gutierrez said his socioeconomic status rarely made him feel disadvantaged in the application process, due in large part to the availability of resources such as fee waivers and counseling at Paly, specifically the College and Career Center.

“There’s a lot of resources at Paly that help people who are socioeconomically disadvantaged to succeed,” Gutierrez says. “You have to look, obviously, but there are people who want to help you and who will help you if you find them.”

Baldwin, who will be applying to college next school year, has had a similarly positive experience. After attending her first meeting with the C&CC, which is mandatory for all Paly juniors, she opted to abstain from paid college counseling, following in the footsteps of her brother.

“In general, it’s possible to get just as good of an experience preparing for college applications without paying for it as it is to get that experience with paying for it,” she says, adding that Paly’s admissions culture often creates “unnecessary stress.”

According to Baldwin, the C&CC not only engaged her brother in the application process but also recommended that he apply to the college he now attends, yielding an important lesson in college selection.

“There’s a school for everybody out there, and it’s not always going to be the most prestigious or the most difficult to get into school for everybody,” she says. “A lot of people don’t realize that, and [they think] that they all have to get into the difficult schools to get into to because it proves something about themselves to the world or to themselves.”

Senior Evan Baldonado, who also exclusively used the C&CC, echoes these sentiments. Like Baldwin, Baldonado says he tries to actively avoid the competitive atmosphere that the “whole rat race of college admissions” creates, adding that campus culture often drives students to prioritize college brand name over fit.

“People can sometimes think that … the only good school is the one that ranks highest on the rankings,” Baldonado says. “But if you actually take it apart, you can see that there are a lot of good schools and that we shouldn’t be focusing on comparing ourselves to others, rather finding one [college] that fits for us.”

Money or merit?

Chemistry teacher Ashwini Avadhani’s classroom is like any other high school science lab, with laminate countertops and a whiteboard scrawled with upcoming deadlines. But above it are perhaps more pressing reminders — a towering row of college pennants, heavyweight names like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and UC Berkeley tacked side-by-side, crawling urgently across the classroom walls.

The most recent Princeton University addition was a gift from Padmanabhan, who will be attending the Ivy League university in the fall.

Princeton is one of many elite colleges which practices legacy admissions, granting preferential treatment to those with family ties to the university. Padmanabhan’s parents both attended Princeton, and he says that this is what compelled him to apply in the early admission round, when he believed his legacy would prove most helpful.

But legacy also put Padmanabhan’s admissions prospects in the limelight. According to Padmanabhan, he has never explicitly told his peers about his parents attending Princeton — yet, somehow, it “got out.” This only intensified the college admissions-related stress, he says.

“Because I had legacy, I couldn’t express anxiety with the [admissions] decision even though I was [anxious],” he says. “I felt like I couldn’t, because legacy definitely does give you a boost.”

Beyond limiting his peer-to-peer interactions, Padmanabhan says it also led to judgments about how qualified he was as an applicant. He compares this experience to that of underrepresented minorities — whose ethnic backgrounds may be favorably considered under certain holistic admissions practices — and recruited athletes.

“That [judgment] sometimes happens with athletes — [that] you got in because you’re an underrepresented minority or something like that,” he says. “Being a legacy applicant, it does have a feeling of diminishing your application or your accomplishments even though it’s something you can’t control.”

This judgment and undermining of qualifications is a feeling with which Gutierrez is all too familiar. As a first-generation applicant and underrepresented minority, it seemed like his deviation from the stereotypical mold of an elite-college admit was apparent to all his peers.

“I think a lot of people didn’t even expect me to even apply to a school like Stanford,” Gutierrez says. “I don’t like how people are surprised that I got in — like, why are you surprised that I got in? What is different about me than some Indian dude or Asian dude?”

“Because I had legacy, I couldn’t express anxiety with the [admissions] decision even though I was [anxious]. I felt like I couldn’t, because legacy definitely does give you a boost.”

— Nicholas Padmanabhan, senior

Four more years

Despite the weighty reputation of the university that Gutierrez will be attending, for him, his goal has remained constant — his college education is an invaluable tool, he says, that will allow him to provide his mother and his family with a better life in the same way that she did for him.

“I always dreamed big — I shot my shot and it went in. So I think people should dream big, especially people like me who think there’s no way to get out of the hood,” Gutierrez says. “But there’s always a way.”

For Wu, however, her admission to an elite college has prompted her to reconsider how her undergraduate education has shaped her sense of self.

“After you get into the elite college, you feel special in some sort of way. But then after coming here … everyone here is at the top of their class, and once you get here you’re not going to be at the top of your class anymore,” Wu says.

It is this distinction between prestige and true educational value that leads Wu to emphasize the importance of self-determination rather than external validation.

“An elite college doesn’t really change much about the trajectory of your future,” Wu says. “You still carry a lot of stress — your life isn’t better because you go to a certain school … I’m sure my life would be similar if I went to a different college, and my friendships would be similar.”

![LESSONS IN LEGACY Senior Nicholas Padmanabhan displays two of his acceptance letters. Padmanabhan will be attending Princeton University in the fall, following the footsteps of both his parents. "I think if they [his parents] hadn't gone to an elite school like Princeton that the expectations would not be there," Padmanabhan says.](https://verdemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMG_7491-1024x683.jpg)