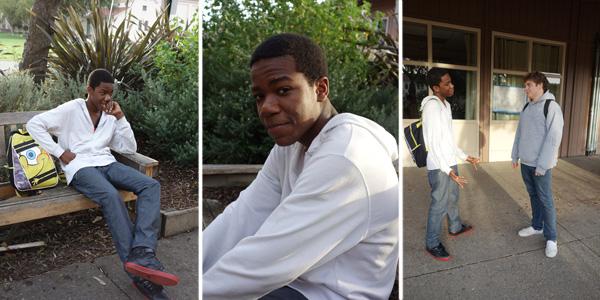

FROM MOZAMBIQUE TO AMERICA Edilson Ngulele, pictured above, moved from Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, to California in August as a year-long exchange student. He frequently hangs out with his brother, sophomore Adam Asch, and has slowly adjusted to American cultures and customs.

For Edilson Ngulele, everything is awesome. This includes homework, chores, homesickness and sleep deprivation. When Ngulele, a 16-year-old Mozambican exchange student, arrived in Palo Alto, his English was composed primarily of parroted phrases from his host brother, and his response for almost every emotion, event or reply became “awesome.”

Ngulele regularly sports a “Giants 2010 World Series” snapback, a black hoodie, a brightly contrasting logo t-shirt with an unrecognizable pattern on the front and sleek black and red-rimmed Nike Airs: the typical wardrobe of the American male teenager.

But, the first baseball game he ever saw was this October’s Game Six of the semifinals to the World Series between the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals. You will frequently find him listening to foreign music on the online Mozambican radio station SFM 94.6.

He speaks in short, fragmented sentences, with a bold accent, and when he opens his mouth to talk, he often wears a pensive expression, focusing on what he is about to say. The only soccer he has played is without shoes in the middle of a cracked, dusty street.

Ngulele’s atypical experiences distinguish him from the students who pass him on Palo Alto High School’s quad.

Ngulele, from the African country of Mozambique on the Southeastern coast, was selected along with eight other high schoolers from thousands of applicants by American Field Service, an international exchange program searching for students to send to the United States.

This past August, Ngulele stepped off the plane in San Francisco International Airport to the greetings of his host family, the Aschs. Palo Alto became his new home for the year.

MOZAMBIQUE

In Africa, there are more than 2,000 spoken languages, and the languages of Mozambique represent only a fraction of this diversity.

As a result of Portuguese colonization in the 16th century, most Mozambicans are taught and speak Portuguese, which is the primary language. Most schools also teach kids English and French beginning in sixth grade, and many, like Ngulele, are also familiar with local African traditional languages.

“At home, I speak Portuguese,” Ngulele says. “The main language is Portuguese, but not everyone speaks Portuguese. For example, like old people, like my grandma. She speaks Portuguese, but she speaks more the traditional language [Shangana].”

A large majority of Mozambican pop and film culture has American roots, which explains Ngulele’s knowledge and acclimation to many aspects of American life.

“We listen a lot to American music, and Brazilian [music],” Ngulele says. Ngulele is also very familiar with American movies and TV shows — in Mozambique there are Portuguese subtitles — his favorite movie being “Skyfall.”

Beyond the typical teenage activities, he watches reruns of two American shows that he owns on DVD.

“When I turn on the TV that’s all I watch: ‘Smallville’ and ‘Heroes,’” Ngulele says.

FAMILY

When he was 12, Ngulele, along with his two parents and two brothers, moved from the small, rural community of Mabalane, a dusty, open, rural town along the Limpopo River, to Matola, a suburban neighborhood a few miles away from the bustling city capital, Maputo.

“It was like moving from a place like Palo Alto to San Francisco,” Ngulele says.

Ngulele is close with his two younger brothers, Junior, 3, and Lorenzo, 12, and gets along well with his parents. His father, Cremildo, is a biology and chemistry teacher at a local school and his mother, Alexandrina, works at a public library in Maputo.

“Me and my brother are so close,” Ngulele says. “He has his own room and I have my own room, but we sleep in same room because we spend a lot of time talking in the night.”

Paly sophomore Adam Asch, Ngulele’s host brother, says he has formed a strong bond with Nguele. Asch quickly got to know and learn about Nguele, who is only a year older than him.

Asch was originally one of the only members of his family who could interpret Ngulele’s desperate attempts at conveying his meaning through hand gestures and pointing.

Initially, Ngulele was homesick and hesitant in his new environment, and Asch admits that he was worried Ngulele would be extremely introverted and shy. However, he has transformed into quite the opposite, according to Asch.

“I thought he was going to be quiet and reserved, he seemed very studious for the first couple days of school,” Asch says. “And he’s not exactly like that. He’s very goofy.”

UNITED STATES

Since living with Ngulele, Asch has noticed many of Ngulele’s habits which have surprised him, and made him more conscious of his own actions.

“He’s much more aware of things that I wouldn’t be aware of, which is good because it has taught me things,” Asch says.

He goes on to describe an incident at the dinner table when he fed the last morsel of steak to the family dog. Ngulele had an unexpected reaction.

“He [Ngulele] was freaked out by that,” Asch recalls. “He was like, ‘You know there are people in Africa who don’t have anything to eat. Why are you giving this to your dog?’ That never even occurred to me.”

Although Ngulele enjoys the constant new experiences and qualities of America, he also misses his Mozambican surroundings and culture.

“Since I moved here, when I Skype my family, they say I’m changing,” Ngulele says. “Mainly my wearing clothes because I wear American jeans, some shoes [Nikes]. At home [I] just [wear] some shorts, sandals, and I have traditional clothes.”

While Palo Alto’s diversity fascinates Ngulele, he still appreciates the unique and distinctive African culture, which, he says adds a feeling of unity.

“I miss the culture,” Ngulele says. “In Palo Alto there is a lot of people from many parts of the world, so I don’t see one specific culture. In Mozambique you can walk in the streets and see people dressed in a specific way, with some traditional clothes, things on the head, a baby here [over the back]. There’s like a whole culture.”

SCHOOL

In Mozambique, Ngulele, a junior, attended Matola Secondary School, where classes begin in January and end in October. Matola Secondary, which is much smaller than Paly, has individual classrooms that spread out over a large area of land.

Paly classes may seem overcrowded, but try learning in an environment where the entire grade — about 60 students — is packed into one class.

Although he has only been in the United States for a couple months, Ngulele’s English is highly developed, partly due to the English education he has received since sixth grade in Maputo.

“In Mozambique, we have English class, but it’s not like English class here,” Ngulele says. “They only teach us simple dialects and conversation.” However, since arriving in America, Asch says Ngulele’s English has improved immensely and he has expanded his vocabulary, grammar and fluency.

“When he first moved here I actually did understand him, but my family couldn’t, anyone else couldn’t,” Asch says. “My mom would explain everything to him, like, butter —”

“B-U-T-T-E-R!” Ngulele interjects, remembering the moment Asch refers to. “It’s a yellow thing that you put in the bread, you eat it.” Ngulele mimics his host mother, who would motion and signal with her hands in an over-exaggerated manner of explanation.

“That was the worst one, but there was other stuff too,” Asch says. “I could understand it, but most people couldn’t understand him. Now, anyone can have a conversation with him.”

Ngulele has also been surprised by the attention and extra help he has received from teachers here at Paly who are helping him catch up and complete schoolwork due to the language barrier.

“The teachers here really want you to understand the lesson,” Ngulele says. “They go and sit with you — they have time to do that. But in my country, it’s different. When the class is over, it’s over. You can go talk to the teacher, but it’s not the same here [at Paly]. You can even have a Saturday morning to sit with you. In Mozambique, who will do that?”

Nevertheless, he is not used to the amount of time spent in school and on homework compared to his previous five-hour school days, which had little to no outside work.

“I don’t think we need to come all day in school,” Ngulele says. “In Mozambique school start at 7 a.m. until noon, and that’s it.”

Although Ngulele is not used to attending school all day, he has become a star in his chemistry class. According to his teacher Ashwini Avadhani, his enthusiasm and stories inspire and inform other students.

“He is a big part of our class,” Avadhani says. “And when he talks, believe me, everybody listens. It’s like pin drop silence because everybody wants to know what Edi has to say.”

Avadhani adds that the class expresses extreme interest and curiosity in Ngulele’s stories and comments.

“He talks a lot about his home and how the students are, how schools are back there and how the relationship between students and teachers is very different,” Avadhani says. “People [classmates] are like, ‘Wow,’ there’s this whole other world that they have no clue about. We get a flavor from Edi which is really neat.”

FUTURE

Both the Asch family and Ngulele have many items on their list of things to do before Ngulele’s departure back to Mozambique in seven months.

“He thought Palo Alto was a big city, and he thought L.A. was a really big city, so I think it would be cool if he went to New York,” Asch says.

Asch also has a few things he hopes Ngulele will remember and bring back with him once the year is up.

“I hope he brings back stories,” Asch says. “I hope to be the butt of a lot of jokes when he goes back to Mozambique.”

One of Ngulele’s biggest challenges is combating homesickness. Besides his friends and family, Nguele misses other aspects of Mozambican culture like its music, festivals and friends. And, of course, he can’t forget food.

“There’s no food in this world that’s better than my mother’s food for sure,” Ngulele says passionately. “It’s other level.”

Currently, Nguele simply hopes to continue learning more English, getting help in school and living for the little moments in life that remind him that he’s in America. Even though he comes from 10,764 miles away, Ngulele’s distinctive characteristics simply add to the intricate, diverse, accepting population at Paly.

“I like him because he’s a go-getter,” Avadhani says. “I like that fight. He’s like any other kid, like any other teenager would be.”