The soft melody of a harp dances in the air as the wine-colored curtains sweep aside to reveal actors clad in modest skirts, black kitten heels and sky-blue tailored suits.

Palo Alto High School junior Derek Zhou’s booming voice cuts into the gentle tune, his shouts reverberating throughout the theater. An actor in a dashing pastel suit drags Zhou onto the stage.

“Get me out of here! What are you doing?” Zhou yells. He stomps his feet wildly, clutching a brass saxophone, his actions intensified by the stark contrast between his tan sherpa jacket and the refined formal wear of the actors around him.

To some, Zhou, an Asian-American student, may look out of place among the velvet chairs and creaking 20th century wooden chests. Set in the 1940s, Paly Theater’s latest production “Heaven Can Wait” was set during an era when the Asian-American population was miniscule. A picture of a typical scene in 20th-century America hardly would have warranted the inclusion of any people of color, let alone Asian Americans.

Yet in “Heaven Can Wait,” a romantic comedy set in Los Angeles, three out of six principal characters were played by Asian Americans. Zhou played the protagonist, Joe Pendleton, a passionate and reckless aspiring boxer who, after dying unexpectedly in a plane crash, is reincarnated as a successful banker. He was joined by many other Asian Americans, among them senior Emily Zhang, the second lead, and junior Annie Tsui, a supporting lead. Zhang’s character, Jordan, is Pendleton’s accomplice, while Tsui’s character, Betty Logan, is Pendleton’s protective love interest.

“When it comes down to the essence of theater, pretty much everybody’s the same.”

— Kathleen Woods, director of “Heaven Can Wait”

Broadening the spotlight

Zhou is optimistic that mainstream productions will follow in Paly Theater’s footsteps.

“I don’t know if this is the start to everything [more representation],” Zhou says. “But I really hope so.”

The casting of “Heaven Can Wait” reflects changes that Asian Americans like Zhou hope to see in the broader picture of professional theater productions.

For instance, the breakout production, “Hamilton: An American Musical,” which chronicles the life of Alexander Hamilton, cast people of color as characters who lived in revolutionary and early America.

In the original production, African-American Leslie Odom Jr. played Aaron Burr and half-Chinese Phillipa Soo played Elizabeth Hamilton. The critically acclaimed musical set a record for the most Tony nominations in Broadway history, and snagged both the Pulitzer Prize and a Grammy award.

“Hamilton’s” popularity on Broadway — and in popular culture — demonstrates that a production can achieve success while exhibiting a racially diverse cast. It also shows a positive example that actors of color can play characters in historical contexts where people of color are not heavily involved, emphasizing an actor’s personality above their race.

The casting methods employed by “Hamilton” have yet to affect mainstream production casting. There still exists a significant representational disparity between the racial makeup of the actors cast on Broadway and that of the general population.

According to the Asian American Performers Action Coalition, around 80 percent of all Broadway roles have been played by white actors for the past seven seasons. However, in 2016, the U.S. Census Bureau found the U.S. population to be only 61.3 percent white.

The same U.S. Census Bureau study found the U.S. population to be 5.6 percent Asian, yet in the beginning of the 2014-2015 Broadway season, just 2 percent of actors were of Asian descent, according to the same AAPAC study.

It also reported that “The King and I,” a play set in 1860s Thailand, single-handedly boosted this figure to 11 percent during the 2014-2015 season. Though the increase in Asian representation was beneficial in raising the amount of Asians on Broadway, the decision to cast such a significant number of Asian actors was driven by their race, not their abilities.

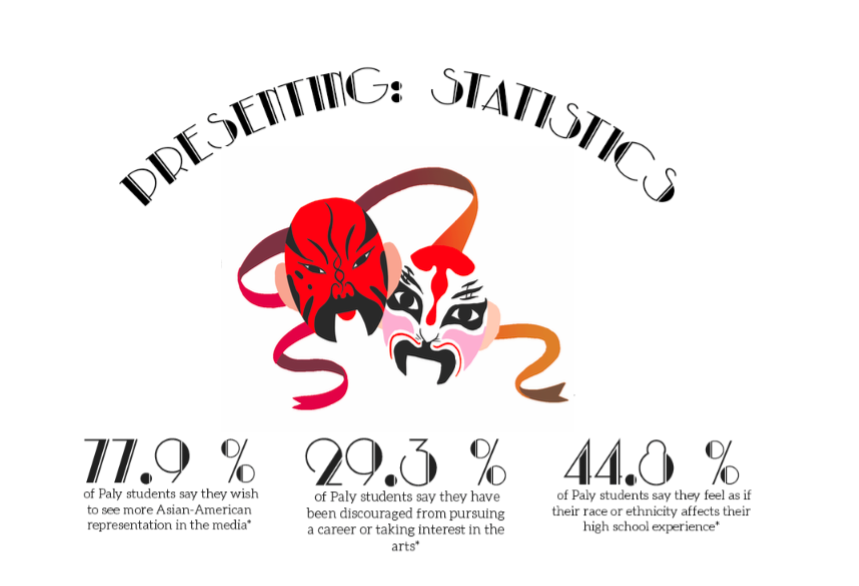

*The student poll results collected from this edition are from an online survey done in 16 randomly-selected Paly English classes over the course of November 2017. 354 anonymous responses were collected. Art by Aisha Maas.

Open stage

Despite the disheartening disparity between Palo Alto and the nation as a whole that seem to hint at yet another “Palo Alto Bubble”, local efforts to promote diversity and avoid discrimination are well underway. Senior Nandini Relan, the assistant director for “Heaven Can Wait,” says Paly Theater strives to promote inclusivity through discussions on race. Relan says that in class, students discussed when it is and is not suitable for an actor to play a character of a different race.

“Paly Theater is very aware,” Relan says. “Last year in my theater class we had long conversations, because at the very end of the year we had a unit where we were supposed to play a character of a different race.”

Paly Theater also employs “color-blind” casting, according to Relan. “Color-blind” casting is where an actor’s race or ethnicity has no effect on their consideration for a role, regardless of a production’s time period and setting.

According to Kathleen Woods, theater teacher and director of “Heaven Can Wait,” professional productions may take race into account to maximize profit, while schools aim to include anyone who is interested in theater, placing maximum value on an actor’s skills or potential.

“Theater is about the human experience, and there are a lot of different ways that you can portray a character, portray a role in theater,” Woods says. “And when it comes down to the essence of theater, pretty much everybody’s the same.”

Paly Theater’s efforts have evidently been effective. The cast of “Heaven Can Wait,” numbering 30 people, boasts 12 actors of Asian descent, a whopping 40 percent. In comparison, the 2010 Bay Area Census reported Santa Clara County’s Asian population to be 32 percent. The number of Asian actors in Paly Theater’s most recent production not only met, but exceeded, the number necessary for a proportional representation of the local Asian population.

Outside the playhouse

Although Tsui and Zhang have attained success through Paly Theater with principal roles in “Heaven Can Wait,” they say they have encountered prejudice while auditioning and acting outside of Paly Theater.

“The unfortunate reality is, the majority of roles that producers and directors will make available to AAPI [Asian-American Pacific Islander] actors are more stereotyped and call for actors to project their foreignness over their humanity,” Andy Lowe, an Asian-American industry professional, says. Lowe is the production manager of East West Players, the longest-running theater of color in America.

While Tsui, a California State Student Thespian Officer, was living in China in middle school, she acted in a short film. Tsui says the director mentioned that her eye shape had a negative impact on her acting, and that unless she adjusted her position in a certain scene to make her eyes visible, she would be replaced by another actor.

“That was definitely a very pivotal moment for me,” Tsui says. “That’s when I realized, ‘Hey, the industry isn’t nice’ … you have to find a way to combat what society thinks are flaws.”

Zhang, who hopes to major in theater and serves as the president of Paly’s Thespian Society, says she was told she was unfit for a role because she is not white while participating in a summer program in Chicago.

According to Zhang, every other classmate had six to seven choices for roles they could play in a number of productions, but when it came to her, the instructor struggled to find one. Zhang says that even when the teacher found a role in a play set in the modern day that had no race specifications, he refused to assign it to her.

“You’ll run into people — like directors, other actors — people who will discriminate against you, and people who will make it harsh,” Zhang says. “You may have to get over the fact that these things will happen.”

Home is where the heart is?

On top of the difficulties Asian-Americans face in being cast, some are discouraged by their families from pursuing theater as a hobby or career. Tsui says she believes this factors significantly into the lack of Asian representation in theater.

When Tsui speaks with her Asian-American friends about auditioning for productions, she often hears the same reply.

“Nine out of 10 times if they say they’re not going to audition [they say] ‘because my parents think theater is a waste of time,’ or ‘my grades are really bad right now,’” Tsui says. “Theater is a really large time commitment.”

In fact, a study published by UCLA’s AAPI Nexus using data from 1998 to 2000 found that Asian-American students experience the highest expectations to major in science and engineering.

Furthermore, the study also reports that Asian-American students tend to “formulate certain negative self-perceptions associated with their inclination towards science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.” Consequently, 30 percent of Asian bachelor’s degree recipients majored in STEM, the highest proportion out of any racial group, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education.

Kathy Yan, who graduated from Paly in 2017 and is currently studying theater at Northwestern University and completing a module in theater management and design, recounts experiencing judgement from family and friends who expected her to pursue a career and obtain a degree in a STEM-related field.

“They’d tell me all about how little money I’d make, how smart I was and how it would be a waste,” Yan says. Though Yan, who originally intended to attend medical school, ultimately decided on a degree in the arts, her older brother attended Harvard University and majored in computer science and mathematics.

“It kinda makes you wonder if I’d still have the okay to pursue theater if my brother had not already fulfilled the ideal for our family,” she says.

“It can feel like I’m there as the token minority you see on college brochures.”

— Kathy Yan (’17), current theater major at Northwestern University

Behind the curtains

Stage technicians have a different perspective on discrimination against Asians in theater. Senior Samuel Kim, the sound designer for “Heaven Can Wait” and student technical director of Paly’s Thespian Society, has not felt marginalized because of his race at Paly.

“I think it’s really different because obviously we’re a public school … we’re a pretty accepting community,” Kim says. “I know that in the greater theater community, much of acting and casting is whitewashed or white in general.”

Furthermore, Yan notes that a small percentage of students studying theater at Northwestern are Asian, and this has caused some feelings of isolation.

“It can feel like I’m there as the token minority you see on college brochures,” Yan says.

Act IV: Epilogue

Paly Theater seems to be a haven for Asian-Americans interested in acting. Yan estimates that at Northwestern, less than 10 percent of theater students are of Asian descent, compared to Paly Theater’s much greater Asian population. Consequently, she did not experience as much discomfort in high school.

“Theater was kind of the only thing I enjoyed [in high school],” Yan says.

Zhou has also encountered racial prejudice in theater programs outside of Paly, and says that Paly Theater is more inclusive compared to outside programs.

“They [Paly Theater] have been really good about giving different people opportunities, no matter their race,” Zhou says.

As the last act of “Heaven Can Wait” comes to a close and the lights fade, the inclusivity that Zhou mentions is clear. Showered with cheers and applause, the actors line up side by side, clutching each other’s hands, and take a collective bow.

Zhou and Zhang, whose characters Pendleton and Jordan develop a sense of camaraderie over the course of the play, step out from the line. Beaming, they both bow once again as they enter the spotlight, and the cheers escalate in volume.

While the ideals of equality championed by Paly Theater have yet to become standard in the greater world of professional theater, its efforts signify a hopeful blooming of progress.

“‘Oh my god look, an Asian actor, that’s so cool’ — that shouldn’t be something that I have to notice,” Relan says. “Hopefully in time it’ll become normalized. In time, the younger generation, when they grow up and they’re actors and directors, they won’t be thinking twice about it.” v