The drumming of the heavy rain outside is drowned out by the chorus of voices that rises every few minutes as another person begins a phone call with the signature question: “Have you decided who you’ll be supporting in the primary?”

It’s March 13, a week after Super Tuesday, and around 15 people are sitting inside the home of Amy Rao, a former Palo Alto High School parent, making phone calls to campaign for Hillary Clinton.

As we walk in, Rao opens the door to greet us and then scurries off to help a woman set up her devices. Another woman, wearing a glittery Hillary Clinton shirt and a “California for Hillary” pin, walks around the house trying to find service on her cell phone. Out of luck, she leaves, promising to “call for Hillary all day” from her home.

Rao has supported Clinton since her run for Senate in 2000 and has hosted many events for Clinton’s presidential campaigns. One of the most prominent fundraisers in Silicon Valley, Rao is important enough to warrant calls from Hillary Clinton herself. According to the Washington Post, when Hillary Clinton announced her first candidacy for president in 2008, she called Rao on the morning before she made her announcement, and Rao’s efforts to raise small individual donations were key to Clinton’s win in the California primary.

Rao is part of an increasingly powerful locus of political activity and fundraising for women in politics in Palo Alto. A political action committee supporting female candidates is housed across the street from Paly and several prominent female fundraisers live within blocks of the school. Candidates hold dozens of events in this area, all striving to get affluent members of the Silicon Valley tech industry to fund their campaigns and bring about a new era of women who have powerful political positions.

In Silicon Valley, where the majority of federal representatives are women, this hub of influential fundraisers seeks to elect more women to political office and collaborates with organizations on both sides of the political aisle to accomplish that mission.

It is not just female organizers who are powering this political machine. All over the country, especially in California, female candidates are also making their mark. The California Senate race this fall will mark one of the few times that female Senate candidates run against each other, as Democrats Kamala Harris and Loretta Sanchez face off over the seat recently vacated by another female Democratic senator, Barbara Boxer.

Now, with Hillary Clinton running to become the first female president, the organizations and fundraisers supporting female candidates are more active than ever.

Why Does it Matter?

Especially on the national level, the gender gap in politics is enormous. In the United States, there is yet to be a female president, and in almost every sphere of politics, women hold less than a 20 percent margin.

“In a world where half the people are girls, it doesn’t make sense to me that we haven’t had one leading the country,” says Arjun Parikh, a New York University sophomore who graduated from Paly in 2014 and attended Rao’s event. “It would be hard for her [Clinton] to be in office and not make positive change for women.”

Although the infrastructure for women’s organizing online has substantially improved since 2008, the imperative for women to fundraise early is still present.

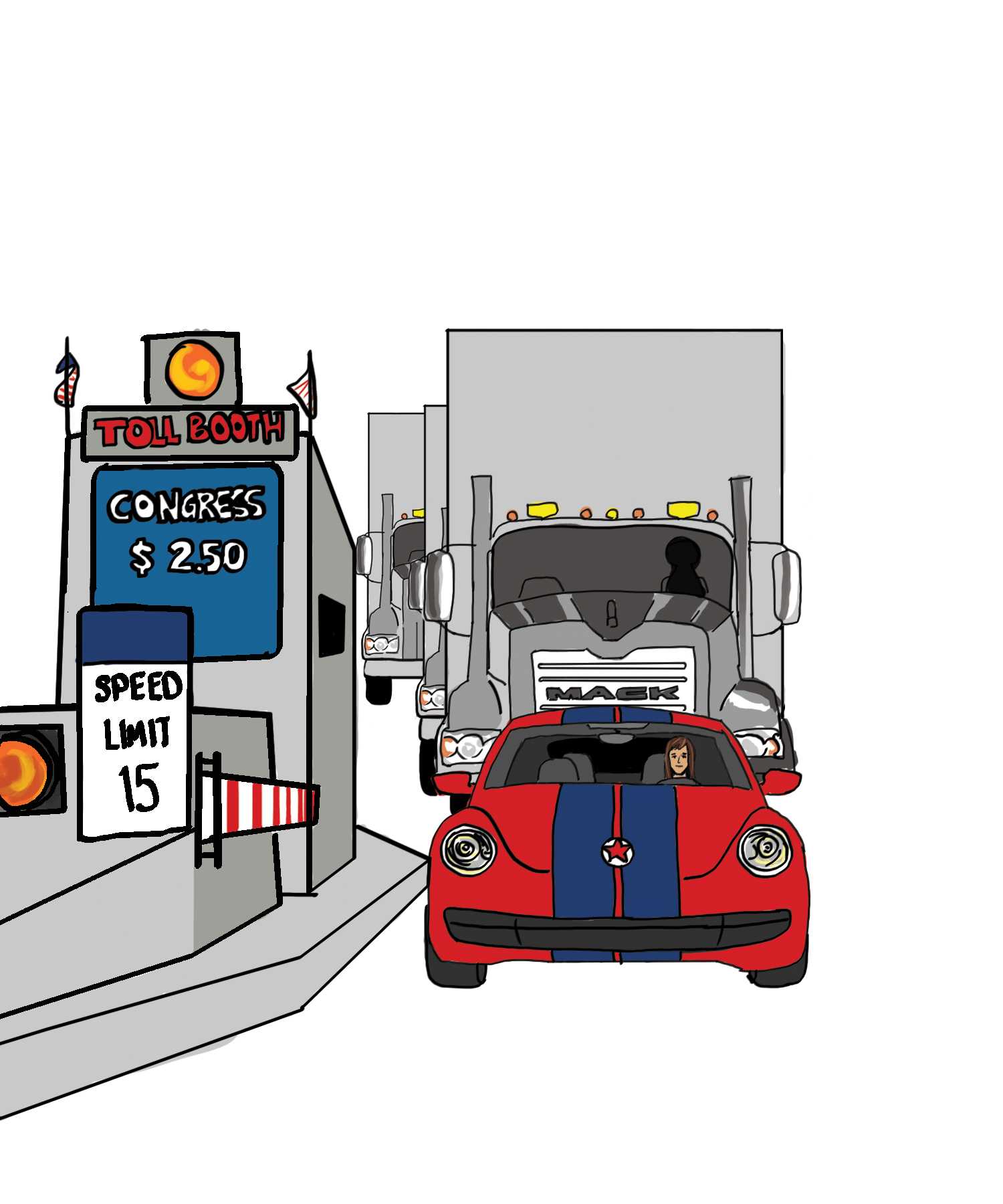

“You can be the best candidate and you can have the best stances on issues, but if you don’t have money that you can use to buy airtime or build up a staff, you are not going to be a successful candidate,” says Lande Watson, a former Verde writer and Paly graduate from 2014 who worked at the political action committee EMILY’s List last summer.

An additional impediment to female candidates is that women are far less likely to run for office than men are. According to Watson, despite women and men having roughly equal win rates, male candidates far outnumber their female counterparts.

“That’s something that they talk about a lot at EMILY’s List,” Watson says. “Women when they’re asked [whether they’d run in the future] often say no because they think they have to have all of these qualifications whereas men are very quick to say, ‘Yeah, I’d run for office. I went to a PTA meeting once, I could be a leader.’”

Part of this problem also arises from the challenges that women face fundraising. In California, such difficulties are compounded by term limits on local seats, according to Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren, who graduated from Gunn High School in 1966 and represents the 19th Congressional District located in San Jose and Morgan Hill.

“Your first race is always the toughest,” Lofgren says. “You have to raise the money [and] you’re not an incumbent. With term limits, that happens over and over again, and so if women have the hardest time being the first-time candidate, making first-time candidates more frequent has an adverse impact on women in office.”

Once women do enter the race, they face a level of scrutiny that their male competitors do not.

“Not only are female candidates judged on the content of their ideas but also on superficial features,” says Anmol Nagar, a Paly junior and current vice president of Paly’s Associated Student Body. “Headlines are made when a female candidate’s makeup was too much or pantsuit was a new color, which I think takes away from the main focus of their campaign. I think that once elected to office, they are also held to a higher standard in terms of their public persona, or how friendly and ‘likeable’ they are.”

A book by Anne-Marie Slaughter titled “Unfinished Business: Women Men Work Family” also highlights studies and personal experiences that show that when a group of men discusses politics, they are unlikely to discuss typically “female” topics like childhood education and women’s healthcare.

“You find that when you add a woman to the mix the conversation becomes broader,” Rao says. “In fact, the more women you add to the mix, the more engaged men will become on the topic … I can’t think of a single issue that isn’t a woman’s issue.”

Even if every issue is a woman’s issue, issues such as education, women’s health, and for Democratic women, reproductive rights do tend to receive more attention when women become involved in the political process.

“I think that the attack on women’s reproductive rights would just completely stop if we had more women in politics at senior levels,” says Paly parent Lauren Segal, who attended Rao’s event.

Sophomore Noga Hurwitz, who is involved with Paly ASB and serves on the regional board of a local youth group facilitating programming, agrees with Segal that being a woman makes her more passionate about being pro-choice.

“I’m very actively pro-choice, and I think part of that is it’s my right that’s potentially being taken away,” Hurwitz says. “It’s something that I feel really passionate about. I think that being a woman increases my investment in some of these causes, but I don’t think it changes how I view politics.”

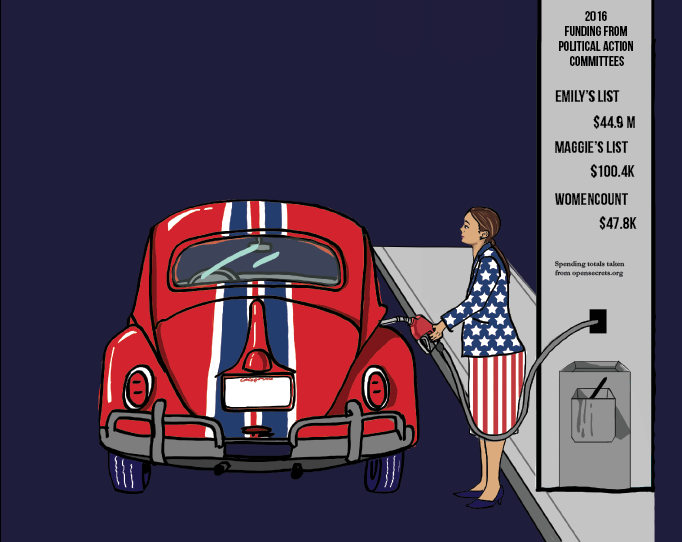

EMILY’s List

Women helping women get elected is a trend that originated long before Clinton’s candidacy. Though many organizations supporting women exist today, their forerunner is EMILY’s List. Founded in 1985 in Washington, D.C., EMILY’s List arose before a Democratic woman had been elected to the Senate. EMILY stands for “Early Money is Like Yeast,” because it makes the dough rise –– an allusion to the idea that early donations have potential to build infrastructure in a campaign’s early stages. Since its founding, EMILY’s List has supported hundreds of diverse candidates for local, state and federal offices.

“Almost one-third of the candidates EMILY’s List has helped elect to Congress have been women of color, including every single Latina, African-American and Asian-American Democratic congresswoman currently serving,” says Jess McIntosh, the communications director at EMILY’s List. “We work with women from the beginning of their careers, building from the ground up through recruitment and training to create a pipeline of future women leaders.”

As one of the oldest organizations in this field, EMILY’s List has a profound effect in terms of respect and financial support. Lofgren used that support when she first ran for Congress.

“I got lists of primarily women who supported women candidates for Congress,” Lofgren says. “They didn’t know me, and I didn’t know them, but the fact that EMILY’s List had endorsed me sort of gave them the message that I was a viable candidate and many of them did contribute.”

Maggie’s List

In 2010, in part inspired by the success of EMILY’s List, conservative women in Florida founded Maggie’s List, a federal organization dedicated to electing fiscally conservative women to the House and Senate. Their name, Maggie, comes from Margaret Chase Smith, the first female senator, a Republican from Maine.

“EMILY’s List has done a fabulous job with their mission,” says Melissa Shorey, national executive director of Maggie’s List. “I just don’t happen to agree with it, and neither do millions of other women. We are giving voice to those women.”

According to Shorey, Maggie’s List faces some challenges as an organization dedicated to supporting fiscally conservative women that more progressive organizations do not, because women are stereotypically thought of as being Democrats. However, the stereotype is not always accurate, as shown by Republican Elise Stefanik of New York. Stefanik, elected at 29, is both the youngest person in Congress and a fiscal conservative.

“This [younger demographic] is something where people often don’t think of conservatives on this issues, yet we’re leading on them,” Shorey says. “We’re electing people on them.”

WomenCount

WomenCount, a national Political Action Committee located in Town and Country Village, was created after the 2008 Democratic presidential primary out of the realization that there was no internet base of women for female candidates to draw from. The PAC hosts a website for Democratic women candidates reminiscent of crowdfunding campaigns.

“Billions and billions of dollars are moving in crowdfunding every year, and none of it is going to candidates,” says Stacy Mason, a Paly parent and the executive director of WomenCount. “What we’re trying to do is engage millennial women, but to do it in a way which feels familiar and comfortable to them.”

Although WomenCount and EMILY’s list do share a similar goal of electing progressive women, the organizations work with different bases of donors.

“We love EMILY’s List,” Mason says. “They have a slightly different focus because they look at everything from a pro-choice lens … and they are directing high dollar donations to women candidates. We are focused on the low dollar donations and multiplying them and building networks.”

The Future of Women in Politics

This election cycle has the potential to be historic for women. With Hillary Clinton as the current Democratic frontrunner, according to RealClearPolitics, it is possible that the next president of the United States will be a woman.

Right now, EMILY’s List, WomenCount and other progressive organizations are focusing on Clinton’s election. For these organizations, the potential of a women president means the possibility of a large-scale shift in the status of women in politics.

“The fact that we’ve never had a woman president is pretty shocking, and it’s really important to show all Americans that a woman can be in this role,” Mason says. “There’s a saying, ‘You can’t be what you can’t see’ … If they [young women] see that this can happen, … we believe it will encourage more women to run for office, which will give us more women to support.”

While a Clinton supporter, Lofgren does caution that having a woman president will not immediately end the gender disparity in politics.

“Some people just don’t think women ought to be in a position of authority,” Lofgren says. “[They think] that women should obey their husbands … and having a woman president is not going to change their view.”

Conservative women have a more complex view on Clinton. While she personally disagrees with Clinton’s stances, Shorey acknowledges that women in leadership positions inspire other women and girls to follow in their footsteps.

“I think whenever you have women running who represent positive leadership, it inspires other women,” Shorey says. “That’s why heroes are so important; that’s why role models are so important. But this is not Hillary’s game — this is for every woman who stands up and leads.”

Regardless of who wins this election, the future of women in politics continues to expand.

“I do think it [the status of women in politics] has made significant progress and it’s just going to keep growing,” Rao says. “When women realize that they can play a part … it really shows women that their voice and their efforts and their checkbook can make a difference. And when you’re part of a movement that’s winning it’s easy to attract more people to your movement. So I expect it to continue to increase.”