Shattered glass storefronts, a blown-in Volkswagen bus, and once, a bloody chicken on a hatchet — these were not uncommon sights in Palo Alto during the winter of 1969. Almost 50 years later, Matthew Stairs still remembers his time as a student at the Midpeninsula Free University when the neo-Nazi violence began.

“It was a turbulent time,” Stairs says. “There was a feeling that people could do anything and it was a surprise to have Nazis in Palo Alto.”

Stairs recalls biking over to his friend Steve Yates’ house on Cowper and seeing his father’s car in pieces, the engine compartment blown up. Harris Yates, a pacifist and a progressive, was one of the first targets of a slew of neo-Nazi hate crimes in the late ’60s.

But hatred in Palo Alto neither began nor ended there.

A half-century later, America is once more wracked with polarization and tension. The recent clash between protestors and neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, Virginia, as well as an increase in alt-right rallies throughout the country — and the Bay Area — sparked a nationwide dialogue about what we stand for today.

“The situation now is even graver,” Stairs says of the national climate. “There is much more polarization. It’s a lot more complicated and messy [now]. Back then, it was the Nazis and everyone else.”

But all politics is local. To make progress, we must first remember the story of our town and the people who came before us.

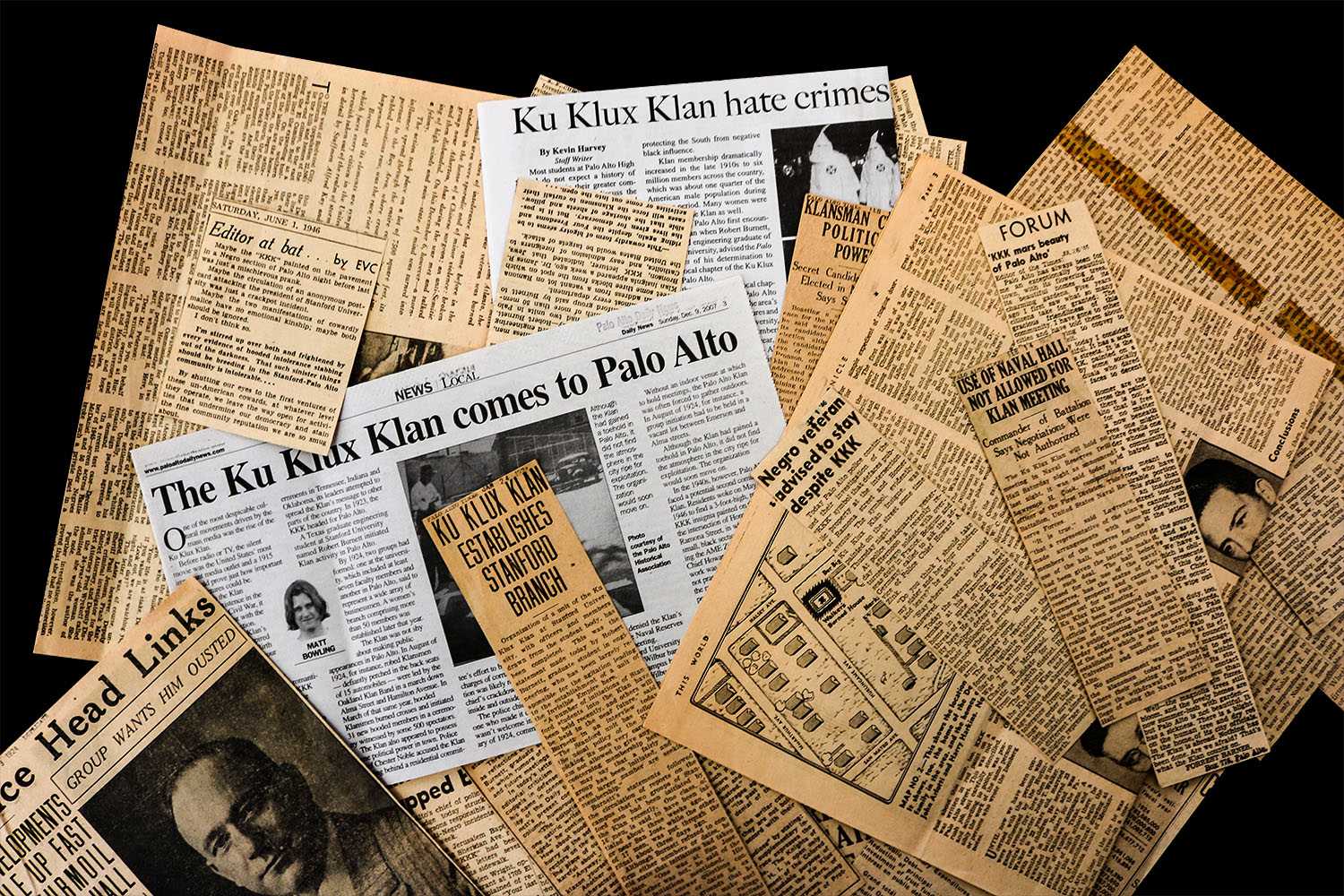

From Ku Klux Klan marches down University Avenue over 90 years ago to subtle racism in our schools today, discrimination remains a part of our lives, according to Palo Alto High School living skills teacher Letitia Burton.

“Look in your own communities,” Burton says. “You start with your home; think globally, act locally.”

Burton says only by looking back can we move forward.

“We’re living in a time where we need to be having conversations … [about] who are we as a community, who are we as a country, what do we believe in, and are we willing to live by our beliefs?” Burton says.

Palo Alto pioneer

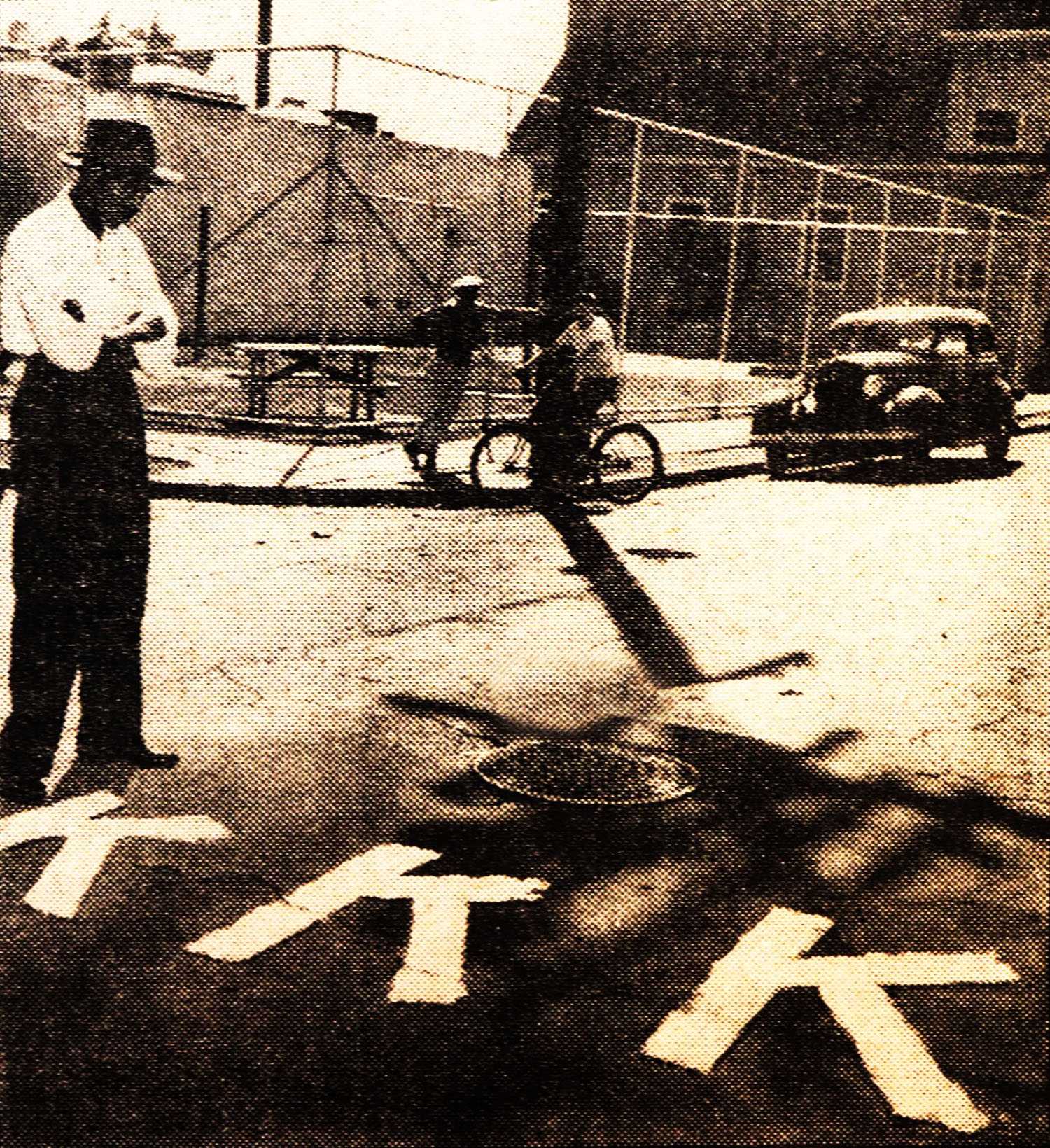

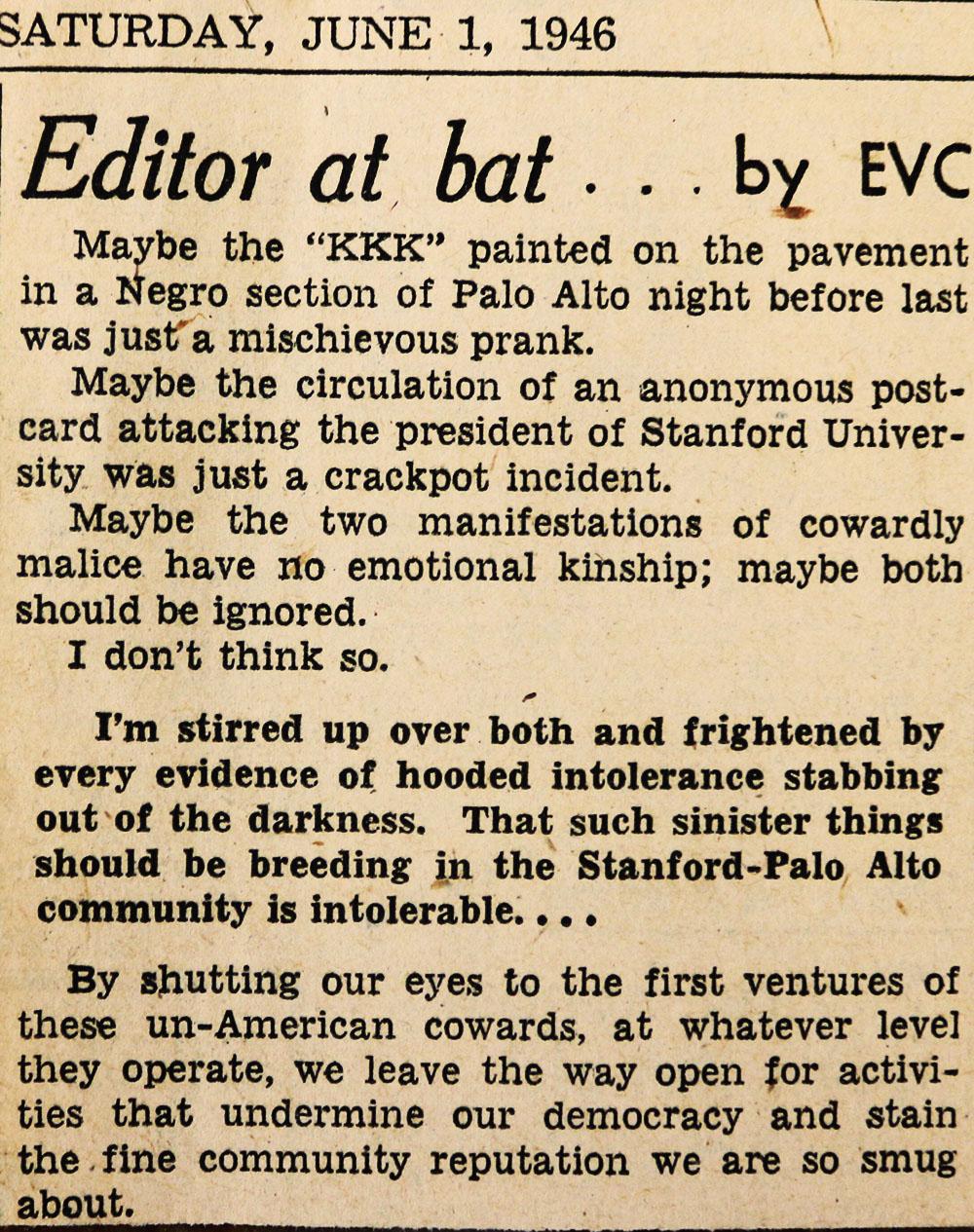

“Maybe the ‘KKK’ painted on the pavement in a Negro section of Palo Alto [the] night before last was just a mischievous prank,” reads a newspaper clipping from June 1, 1946. “Maybe [it] should be ignored … I don’t think so.”

On May 31, 1946, Palo Alto-based Klansmen painted a three-foot-high, red-lettered ‘KKK’ outside the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, the first black church in Palo Alto. This incident was not the first of its kind; after two decades of dormancy, the Klan was back.

Robert Burnett, a Stanford engineering student from Texas, first brought the Klan to Palo Alto in 1923, according to the Palo Alto Historical Association. In March of that year, the KKK set fire to a cross in a public demonstration on Pitman Avenue. In August, they marched down Hamilton and Alma.

By the end of 1924, numerous locals were sympathetic to their cause. Among them was Robert Brister, a long-time resident and small business owner.

So, after the first black church in Palo Alto popped up on 819 Ramona directly across the street from his auto repair garage, Brister was not pleased.

When the pastor came knocking on Brister’s door and invited him over for dinner, Brister declined, according to Jon Kinyon, Brister’s great-grandson and Palo Alto native.

But the pastor kept coming back, inviting Brister over or stopping by with leftovers. At some point, Brister’s prejudices gave way. Eventually, Brister would regularly dine at the pastor’s and attend the black church as much as he attended the white one.

“They [Brister and his family] were completely changed by being in close proximity and realized ‘We’re all human, we’re all the same,’” says Kinyon. “‘We [all] like to have family get-togethers, we’re [all] just people.’”

Like father, unlike great grandson

Generations later, Kinyon bridged the divide Brister had begun to question. Despite judgment from onlookers, Kinyon and his next-door-neighbor, an African-American boy named Keith, were childhood best friends. Race never seemed to matter. Until the day it did.

“In high school, he told me he didn’t want to be seen with me because I was white,” Kinyon says. Years of friendship gave way to jeers from Keith’s friends.

“At that time [the 70s], it was still very hard for black families to get housing,” Kinyon says. “East Palo Alto was pretty much created to be a separate place for minorities to go.”

Although the 1964 Rumford Act had outlawed housing discrimination, the “anti-oriental” and “anti-colored” clauses that littered home ownership deeds disguised themselves in legal loopholes and closed sales doors. Even in 2008, owners of an East Palo Alto complex were sued over allegedly disregarding prospective African-American tenants in favor of white applicants.

“It’s still happening, it’s just not as widespread in the area,” he says. “That was the rule before, now it’s an exception.”

What’s in a name?

From the overt — neo-Nazi bombings and Klan marches — to the covert — housing discrimination and everyday prejudice — addressing our history of discrimination is an issue Palo Altans still wrestle with today.

Drawing parallels between Charlottesville and the renaming of Palo Alto schools, Kinyon urges the community to question the past and question their heroes.

Controversial monuments and contemporary students are juxtaposed in this piece by Vivian Nguyen.

“Change is good,” he says. “You don’t want to get stuck in the past.”

Four years ago, Paly sophomore Kobi Johnsson did just that.

Circa 2014, Johnsson was a seventh grade student with a school project and a question: who is David Starr Jordan?

“We never really talked about him [Jordan] in school and I wanted to know why our school was named after him,” Johnsson says. “When I did the research, I was really shocked.”

Jordan was the first president of Stanford University, a well-respected expert in ichthyology — the study of fish — and a eugenicist. In 1928, he helped found the Human Betterment Foundation, whose reports Nazi eugenics programs later drew inspiration from and used as a justification for hate, according to research by the district’s Renaming Schools Advisory Committee.

Johnsson’s book report, “David Starr Jordan: The ugliness behind the makeup,” would eventually catalyze the petition for renaming Jordan Middle School.

“I hope that it will teach people to be more aware,” Johnsson says. “Research yourself, and if you see something wrong, don’t be afraid to do something.”

Willful ignorance

Upon joining Palo Alto Unified School District over a decade ago, living skills teacher Letitia Burton had already done her own research.

When she mentioned Jordan’s history to her then-co-workers at Jordan Middle School, many of them seemed oblivious to the issue.

“[They] didn’t seem to think it was that big of a deal, or just ‘Oh yeah, I know, it’s kind of too bad,’” Burton says. “Yeah, it is too bad.”

How much Jordan’s name directly impacted students is unclear, but Burton wonders about the implicit impact it had on minorities.

“Knowing some of the issues I was seeing at Jordan, where there were kids who didn’t feel like they were part of the school … raised questions for me,” Burton says. “How much did that name have to do with people not feeling like they belong?”

Whether it’s the lingering namesake of Jordan Middle School or everyday slights, senior and PAUSD Board Representative Richard Islas believes minority students still experience ostracization today.

“There is no more KKK walking down University, there’s even a Mexican on the board,” Islas says, referring to himself. “But it took so much for that to happen. They believe there is nothing there anymore … because of how far we have come. But it [discrimination] is still there. It’s subtle … but it’s there.”

Rather than outright racism, Islas and other minority students face a more systemic disadvantage.

“Paly, right now, I believe is clueless about this,” Islas says.

“Everybody believes ‘Oh, Palo Alto is like a utopia now. There is no discrimination.’ But there is. There are barriers that don’t let students achieve their highest potential, like the achievement gap.”

As an African-American, senior Ladaishia Roberts echoes the sentiment, recalling an incident in her history class.

“When we talk about slavery in class, the white people all look at you,” Roberts says. “Just, like, what the f—, I’m not a slave.”

Though there is no simple solution, both Roberts and Islas believe the Paly community can do more.

“They don’t give us the help we need,” Islas says. “They don’t tell us about what we can do. They all put us in a certain group.”

Camp Unity is one way to spread awareness, according to Roberts.

“I think all students should go to Camp Unity so that it won’t be just up to the Camp Unity students to bring it back,” Roberts says.

Islas, who also cites Camp Unity as a transformative experience in his life, believes events like these are crucial to make students more conscious of implicit biases.

“I’ve heard rumors that they want to take away the camp and they want to even bring it down to one camp per year,” Islas says. “What are a hundred kids going to do to two thousand kids?”

All politics is local

Palo Alto’s story will continue to unfold, for better or for worse — but as local history becomes shrouded in time, Islas stresses the importance of recognizing both progress and past discrimination.

“I think it’s very important to remember … how far we have come and what we don’t want to do again and what we don’t want to be again,” Islas says.

As our nation experiences increasing polarization and turbulence, Burton believes the community must explore questions of remembrance and reform.

“The community needs to ask itself: how can we remember? How can we mark history and say ‘This is where we were but this is not who we are,’” Burton says.

Now, 50 years after the terror the witnessed on Cowper, Matthew Stairs cautions others of passively allowing hateful acts to occur.

“Look at the history books,” Stairs says. “Go to the library and pull up the local newspapers. Your heart will tell you when something is wrong. Bombings scream of it. Even today with more subtle forms of racism or hatred of any kind, always be vigilant and stop it whenever you see it.”

Stairs leaves students today with a final warning.

“Students at Paly: Just do not tolerate any racism, any sexism, any religious bias. Be courageous and just do not tolerate it.”

Read more:

Journalism Ethics in Times of Crisis by Kamala Varadarajan and Ashley Hitchings