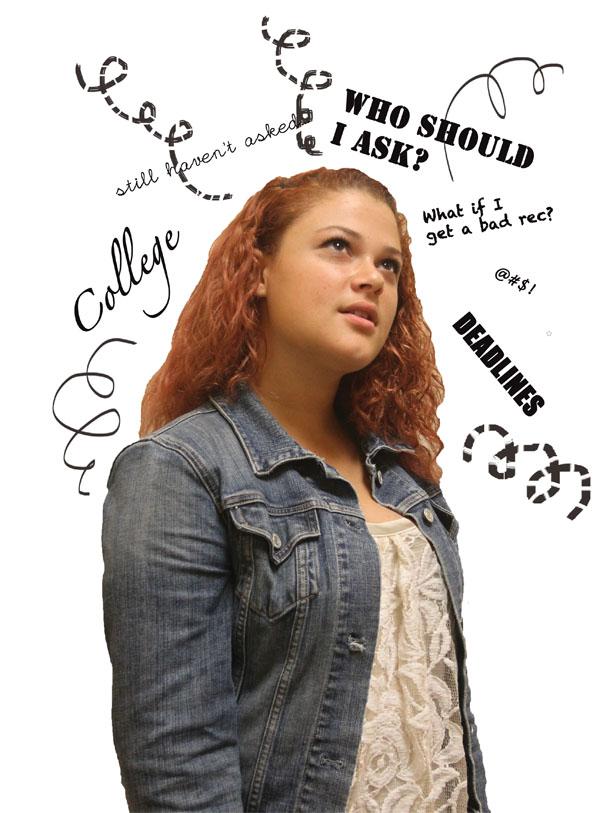

Multiple questions and worries surround the recommendation letter process.

You don’t want to be that one kid. It’s October, the Early Decision deadline is a week away, and you still haven’t asked a teacher for a recommendation letter.

If you could do it again (or if you’re a junior just about to start), where does the quest for good — if not stellar — rec letters begin?

In one place: relationships.

The Paradox of Gamed Relationships

For students like James, who does not wish to be identified by his real name, relationships with certain teachers have never come naturally.

“I tried to form good relationships with teachers, [but it] didn’t always work out,” he says. “I wouldn’t say [my relationship] is fake, but I am TA’ing for both my rec writers, so I wouldn’t know,” he says. To stay on the safe side, James decided to take both Teaching Practicum and an elective taught by one of his rec writers.

Actions by students like James reflect the pressure to “game” relationships and the rec-letter process, something that teachers like Humanities and English teacher Lucy Filppu firmly oppose.

“I’m starting to feel like some students just suck up to you,” Filppu says. “But they have their whole lives to build those kind of fake relationships, and I’m not interested.”

Like many teachers, she believes that people cannot build genuine relationships on the expectation of what they may bring you.

“Some students need to learn the art of relationships,” Filppu says. “Which means you’re just you, present, and enjoying the class.”

But even with the best of intentions, it’s difficult to distinguish between fake and genuine connections.

“That’s really hard: How do you plan for authenticity?” English teacher and upperclassmen teacher adviser Erin Angell says. “There’s something that’s almost counterintuitive about saying ‘Let’s try to game relationships.’”

For others, the distinction between picking teachers and “grooming” them for a rec has rarely been of concern.

“I don’t think it’s so much the students gaming the system, as much the reality of what they have to do to get into college,” math teacher Kathy Bowers says. “Teenagers are teenagers. I don’t know if the teenage brain can think that far ahead and be that manipulative in a year.”

Many students develop these genuine relationships with teachers through their effort, in-class participation, and enthusiasm about the subject.

“When I was trying to think of teachers to request for a rec letter, I thought of the classes in which I asked the most questions and participated the most in class,” senior Yoko Kanai says. “Those teachers tend to be the ones who know me best as a student.”

For classes that don’t have as much built-in discussion, however, getting the teacher to know you well can be harder. AP Chemistry teacher Carolina Sylvestri believes that these personal relationships should be partly initiated by teachers, so that they can find out more about each student.

“For me as a teacher, it is always one of my objectives to get into a good, positive teacher relationship with each student,” Sylvestri says. “I enjoy doing it.”

A Letter Doesn’t Equal Good Letters

When it comes to solid letters of recommendation, character matters more than grades.

Recommendation letters may seem easier to attain when you have solid grades consistently or participate actively. But will having lower grades or staying quiet in class hurt your chances of a good letter?

For the most part, teachers say no.

According to Filppu, the way kids treat others, the attitudes they bring, and the insight they offer in class say much more than an “A.”

“If you’re a B student or maybe you’ve had some errors, don’t ever think you can’t ask a teacher for letters,” Filppu says. “It’s my pleasure to write letters for kids who maybe don’t have stellar transcripts, but have been good people, been respectful, and have brought a ton into the Paly community.”

Though the letter grade may sometimes signal how much effort a student puts into the class, teachers say they look beyond it when writing recommendations.

“There are students who are smart — that’s a given — but what beyond that allows me to distinguish them? That’s what you look for,” says AP United States History teacher and upperclassmen TA John Bungarden.

To teachers like Sylvestri, this kind of insight also doesn’t have to come from speaking up in class. She regards being quiet or discussing the subject with the teacher privately to be just as valuable as actively participating in class discussions.

“I’ve learned over the years to respect the silence of some of my students because the ‘quiet type’ is a very interesting type,” Sylvestri says. “I try to figure out ‘they’re quiet but…’ The ‘but’ is also important. There is a lot of value to silence.”

An anonymous teacher suggests that quiet or struggling students initiate a conversation with the teacher and figure out a situation that works for them.

“If they feel uncomfortable participating in class or working in class with someone, they should have a conversation with the teacher,” she says. “A teacher can’t read a student’s mind. The more a student can be open, the more the teacher can help.”

She agrees that low grades should not deter students from asking for a letter, as long as it’s clear that the student tried his best.

With all teachers, it’s clear that grades do not guarantee a great letter of recommendation.

“If you take up space in the class, but don’t bring anything, why should I write you a letter? You didn’t add to our community,” Filppu says. “They are about your character, not necessarily about your academic performance.”

Does Everyone Get a Yes?

While asking for a letter can take less than five minutes for students, writing the actual recommendation can take hours or days.

“The biggest issue with the recs is that they take a lot of time,” Bowers says. “I don’t put a cap or say no, but I can fully understand why other teachers would, just like I can understand why students need them.”

Bowers says she really “feels for the students in the process,” and wants to help as much as possible. She took on 60 letters of recommendation last year, including 30 as an adviser and 30 as a teacher. On average, each of her letters require three hours to write.

But to some, anything over 30 recommendations is outrageous.

“I do consider it a huge labor of love,” Filppu says. “I don’t template-ize the whole thing. To look up the student’s stuff, to look up the student’s papers, and think back on what I can say about them — each letter can take a lot of time.”

The time cuts into time usually invested in family, outside obligations or lesson plans for regular classes. Without hours carved out in their days to complete all the letters, most teachers opt to finish during the summer, fall holidays or free periods.

“You can take a ‘buy back day’ when you stay home and write,” Angell says. “But you’ll probably get through, at most, six letters, which isn’t much when you’re writing 20.”

The administration has recently tried to honor teachers who write more letters, giving those who take on 30 or more a couple of days off to work.

However, most advisers still place a limit on the number of people they will write for.

“I cap typically at 20 because I’m also a TA. I just can’t do an infinite number,” Angell says. “I will not write a letter of rec if it will not be a glowing letter of rec.”

Bungarden, who doesn’t cap, offers a different perspective.

“At this school, you get really good students who have college ambitions,” he says. “Part of the deal is you’re called upon to write more letters. But if I was a younger teacher with other responsibilities and wrote rec letters outside of everything else, I would understand it’s time taken away from the rest of your life.”

For some students, however, such limits are far from desirable.

“I would like for them to not have caps, but that’s completely from a student’s perspective,” senior Thomas Zhao says.

“I know that some teachers who have reputations for writing good letters of recommendation do not have caps on the amount of letters that they write and are able to finish them all.”

With the issue of turning down students, another question also pops up: Do teachers ever say no because the student isn’t “qualified?”

The response is mixed; some teachers only take a couple of requests every year, while others refuse to write letters that are simply mediocre or neutral.

“If I can’t write [the student] a letter of recommendation that’s going to be really positive, then I encourage them to go find somebody else,” Angell says.

Many students see this policy as beneficial and justifiable.

“If a teacher doesn’t think he can write a student a good rec letter based on lack of information or bad impression, then the teacher would be doing a disservice to the student by [writing a letter and] jeopardizing his chances of getting in,” Kanai says.

But teachers like Bowers recognize the challenges students have finding and asking teachers for recs.

“I’ll write for any kid who needs one,” she says. “I’m not going to base it on an arbitrary number that I write, or how well I know the kid.”

Sylvestri offers similar thoughts.

“If they ask me, I will do it,” she says. “I’m thrilled to do it. To me, to be a part of their steps to college, I feel honored.”

Be Real: Advice from the Writers

Whether you know it or not, teachers notice the little things.

“Be very conscious of how you treat others and your teacher,” Filppu says. “Don’t think we’re always watching you, but I’m very observant and I see a good kid a mile away. Even if they’re sloppy, or ridiculous or fail a quiz — who cares?”

Angell advises students to ask someone who has either seen them excel academically, or someone they have genuinely clicked with.

“You should pick a teacher who, at minimum, you feel like you did some really good academic work for,” she says, emphasizing the importance of participation and edification of other students in class. “The other is [one] you feel you’ve made a personal connection with.”

Timing, which some seniors have struggled with, is also key.

“Everyone says it, but ask early!” Zhao says. “Colleges can see your academic strength from your transcript, and they want to know what kind of person and student you are, so ask teachers who know you and the kind of student that you are and who will speak highly of you.”

In the end, three important pieces of advice stick: Be real. Find someone who will be enthusiastic about you. And finally, don’t worry about getting a “bad” rec letter.

“What we try to do in a letter is highlight the stuff that’s good,” Bungarden says. “There’s always something.”