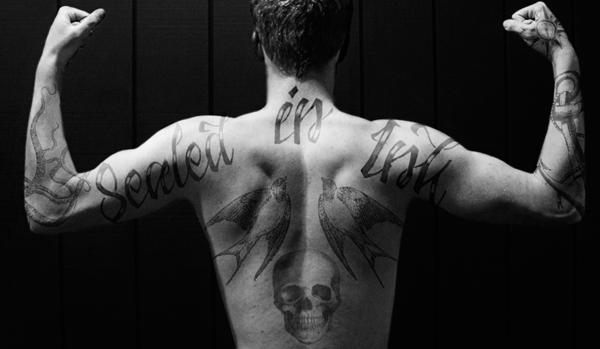

A Photoshopped model demonstrates the importance of tattoo placement. Photo by Charu Srivastava Photoshop by Evelyn Wang

Girl meets boy. Boy tattoos girl.

Girl trades date with boy in return for tattoo lessons.

It’s 1904, and in a scene straight out of a Portlandia sketch, Maud Stevens Wagner agrees to a date with future husband Gus Wagner if he makes her his tattoo apprentice. Since then, countless tattoo apprentices have made just as intense trades: three to 10 years of your life for the right to be a tattoo artist.

But for those who find this arrangement too Faustian for their tastes, there’s another solution: Tattoo schools, which promise to teach all the training required to get a tattoo license and begin legally tattooing for money, all in just two weeks.

However, while tattoo hopefuls have flocked to the schools and the ratings on TLC’s “Tattoo School” reality TV show have soared, many tattoo artists and hardcore enthusiasts have responded less than favorably. Some have even formed online petitions and Facebook groups to boycott tattoo schools.

Here’s where those of you soon-to-be adults, who just can’t wait to get a dandelion turning into a bird flying in an infinity-sign formation, may want to start paying attention. (For the precocious underclassmen in the audience, we’ll deal with you later.) Tattoos are forever, and traditionally trained tattoo artists say that while a properly trained tattoo artist can turn you into a walking, talking Giger painting, a tattoo school graduate can scar you for life.

“As far as the tattoo community at large goes, they detest the people who run [tattoo schools], and they don’t acknowledge anyone who graduates from that school as worthy,” says Karen Roze, owner and tattoo artist at Sacred Rose Tattoo in Berkeley. “You should never tattoo somebody without having proper training.”

To Roze and other traditionally trained artists, “proper” means a full apprenticeship.

During the first two to three years of their apprenticeships, Roze’s apprentices perform miscellaneous tasks and about sanitation and bloodborne pathogens, without ever touching a tattoo machine. When they begin to tattoo, it’s under her supervision and on their own skins. They must work in the shop for another five years before they can leave and begin their own businesses. Although Roze says apprentices are unpaid as a rule, she pays her apprentices minimum wage for working two days per week and allow them to charge $50 for small tattoos and $50 per hour on large ones, of which they get a percentage.

Roze says her shop’s decade-long training builds the necessary skills and respect for the craft.

“It takes years to be good at this,” she says. “Tattooing requires skills and finesse only built up over time and you can only learn it from a master. It’s very similar to woodworking or doing porcelain. You need to work under a master for a certain amount of years to even become competent at it.”

Roze’s current apprentice, Ian Manley, thinks learning tattooing in two weeks is absurd.

“The idea of being proficient in two weeks is unheard of,” he says. “What can I imagine learning how to do in two weeks? Maybe how to quickly and efficiently close down the shop.”

But L.W. Pogue, owner of the World’s Only Tattoo School in Shreveport, La. (which may be world’s first, but is no longer the only, tattoo school), argues the traditional apprenticeship is unnecessary, and even counterintuitive.

“Under an apprenticeship, no one is truly obligated to teach you,” Pogue says on his website. “They do it at their own leisure. And you must also keep in mind that not every artist is an efficient teacher.”

He also says apprenticeships waste time performing tasks irrelevant to tattooing.

“My students don’t come to me to learn how to sweep and make copies,” he says. “We just tattoo. None of the hazing or teasing that comes with ‘traditional’ apprenticeships.”

Unlike Roze, who says she only hires those with formal art school training as apprentices, Pogue accepts anyone into his school regardless of artistic ability, although he does recommend students understand the basics of drawing.

Pogue’s two week course, according to his website, promises a “tattoo license guarantee,” a “full set of professional tattoo equipment,” “plenty of willing human models for you to learn and practice on” and “guaranteed job placement upon completion of coursework,” among other things.

“My course prepares students to become licensed right away,” he says. “They are ready to open a shop right away.”

And some of them did just that, according to the testimonials published on the website.

“This [is] the 3rd week I’ve been back from class,” wrote student Rusty. “My original plan was to do parties and sessions in my home, but I’ve been so busy I feel it’s time to open a shop, which I will be starting that [sic] next week.”

According to Roze, getting tattoos by those who have not been traditionally trained, especially those tattooing out of their homes, can lead to health risks.

“When you’re educating young adults and teenagers, they need to understand this is a medical procedure and they can easily get hepatitis, which is deadly,” Roze says. She lists hepatitis B, AIDS, and tuberculosis among the other bloodborne diseases transferrable through unsanitary tattooing.

In California, efforts have been made to make tattooing a safer practice. Tattoo artists and piercers in California must adhere to the AB-300 law, passed in July last year, which regulates body modification. Among other new restrictions, it requires artists to register annually with a local enforcement agency and specifies strict sanitation procedures.

Even so, people still break the law, tattooing out of their homes or tattooing minors. The latter is a misdemeanor in California, according to California Penal Code 653.

“Unfortunately, they [illegal tattoo shops] don’t get shut down because there’s not a lot of knowledge in the law enforcement community about this,” Roze says.

There also isn’t any regulation against being a bad tattoo artist. According to the San Francisco Health Department, all a tattoo license requires is a photo ID, a blood-borne pathogen training certificate, a hepatitis vaccinations certificate and $25. Even though tthe application asks for a brief background description, Rieth says an apprenticeship is not a legal requirement.

“Licensing is required in California, but there’s no background check on apprenticeships here,” he says.

But Roze says the tattoo industry’s close-knit communities and word-of-mouth advertising help stifle sub-par work.

“If somebody’s messing with the business, I call the shops and say ‘don’t hire this guy’,” Roze says.

But this hasn’t stopped those looking for a cheap tattoo from finding a shop or scratcher (an untrained amateur who tattoos out of his/her home) who will do it for a few bucks.

Kelsey Trier, a Palo Alto High School alumnus, paid $40 for her first tattoo, which she got at the age of 16.

“I got it done in a house by an artist that was formerly licensed and employed in a legitimate tattoo shop but was fired for tattooing minors,” she says. “It was literally just a phone call for me, but it all really depends on who you know.”

But Roze says a cheap tattoo is a warning sign. According to her, the typical minimum for a professional tattoo is $100, with rates usually ranging from $150-350 per hour.

“Don’t shop for the cheapest tattoo, because you get what you pay for,” she says. “There’s an old saying that good tattoos aren’t cheap and cheap tattoos aren’t good.”

Not only do cheap shops do subpar work, but they cheapen the industry as well, according to Roze.

“The price of tattooing has been crushed by the abundance of unskilled people who charge less money,” she says. “It kind of mirrors this complaint about unskilled labor. Like if I owned a construction company, and all the guys down at Home Depot charged 50 bucks a day to do the same work as my skilled, bonded, insured carpenters who want 150 a day.”

Rieth says tattoo schools have made tattooing more mainstream. But he and Roze aren’t sure this is a good thing.

“If anyone can do this, then where’s the special treat?” Roze asks. “It [tattooing] hurts. It should be expensive. They [tattoo schools] are taking the mystery out of it and they’ve created a plethora of new unskilled artists who just sprung up like weeds.”

“Our popular culture is devouring anything that used to be on the fringe and spitting it back out,” Rieth adds. “Some things maybe should remain on the fringe.”