White digits flash across the screen as the number of bitcoin transactions within the last 24 hours continues to climb upwards on the Blockchain website.

Junior Grace Lam, who began mining cryptocurrencies in July 2017, explains the process occurring before her on the screen.

“You can think of it [cryptocurrency] as untraceable cash — invisible cash. There’s a limited amount of it, and it’s all untraceable, because it doesn’t have your name on it, and there’s no ledger, there’s no central account,” Lam says. “It’s all transaction by transaction on the blockchain.”

Lam isn’t alone in her cryptocurrency ventures. Since the first 50 coins were mined by Bitcoin inventor Satoshi Nakamoto in 2009, Bitcoin trading platform Coinbase has attracted over 10 million users and facilitated the transaction of over $50 billion.

The rise in popularity of cryptocurrencies has turned it from a foreign concept into local jargon, shaping the lives of corporations, faculty and students alike in Silicon Valley.

For example, Coupa Cafe on Ramona Street has accepted Bitcoin as a form of payment since 2013, according to Palo Alto Online.

Established giants like Bitcoin and Litecoin reign alongside pop-up currencies like Dogecoin and CryptoKitties, with new currencies emerging by the day.

“It [cryptocurrency] is becoming more mainstream,” says AP Macroeconomics teacher Deborah Whitson, who began incorporating the subject into her curriculum three years ago. “Five years ago, I had one or two students who had heard of it. Now, everyone’s heard of it.”

It’s not only AP Macroeconomics students who have gained a glimpse into the workings of cryptocurrencies — other Paly students, like Lam, with spare cash or spare equipment have joined in on the hunt for digital gold.

Minor Miners

Earning cryptocurrency is a race between machines — whichever computer solves the calculation for a transaction faster earns the largest portion of the profits. Essentially, machines must whir all day to compete with other miners.

Lam and senior Ryan Dickson have taken their success with cryptocurrency investments and transitioned toward mining the coins themselves. Both recognize how privileged they are to mine as students.

“I have a Graphics Processing Unit at home, and a computer that I turn on all the time anyways in order to train for my [robotics] projects and neural networks,” Lam says. “It’s already using the same amount of energy, so I thought, ‘why not just add another process on top of that and mine for Bitcoin?’”

Dickson’s home runs on solar power, which is considerably cheaper than electricity. This allows him to purchase his mining hardware at much cheaper prices with power costs having little impact on energy bills.

Lam’s devices aren’t dedicated solely to mining, causing her earnings to fall short in comparison to those with dedicated machines like Dickson’s.

“For each calculation, there’s a chance that they’ll beat me to it, which means that they’ll get a larger portion of it [the money],” Lam says.

“It’s kind of a shot in the dark. If you do make money, it’s a little bit and it accumulates,” says Lam, who makes anywhere between 30 cents to two dollars per day.

Although mining doesn’t always turn out much profit — sometimes the transfers don’t work out, and sometimes what’s been mined may not transfer at all and will instead get lost somewhere in the abyss of Bitcoin — Lam maintains a positive outlook on the matter.

“It doesn’t hurt. Whatever I make is whatever I make, and even if I don’t make anything, I’m still using the same amount of energy,” Lam says.

Since venturing into cryptocurrencies six months ago, she has made nearly $1,000 off mining.

On the other hand, Dickson says he has made $40 a day passively mining since the summer, after his initial investment of just under $1,000 on his equipment.

“If I included how much my power bill [would have] cut into how much I make every day, it would be dismal — I’d only make five bucks a day,” Dickson says.

“It’s definitely tough to build yourself up there,” Dickson says. “It’s all about the value.”

Cash or credit? Coin.

Mining isn’t the only way students have become involved with digital currency.

Junior Ashutosh Bhown started investing in cryptocurrency stocks in August 2017, thanks to encouragement from his father.

“It started with stocks,” Bhown says. “It [cryptocurrency] is kind of like high-frequency stock trading, just over a longer period of time. [People] trade one microsecond and sell the next, so it’s really rapid profits and losses. I wanted to diversify my trading methods, so I thought, why not?”

Starting with $400 worth of Bitcoin, he currently holds $1,200. Bhown has also collected over 150 Ethos coins, whose value has since climbed from 50 cents to $4 a piece.

“I’m just going to hold onto it and see how it goes,” Bhown says.

Junior Neil Yeung also dove into cryptocurrency this past summer after setting aside some cash and investing in Bitcoin, Ethereum and NEO.

Although mining is financially burdensome for Yeung, he remains hopeful for the future of cryptocurrency applications. Real estate, healthcare and data storage are all on his mind.

“It’s really a global movement. The projects are not just originating from Silicon Valley, they’re originating from everywhere.”

As with any new innovation, cryptocurrency developers are faced with challenges. Transaction speed is among them.

“Bitcoin right now can handle five transactions per second, and Ethereum [can handle] 25,” Yeung says. “For comparison, VISA can handle 2000 transactions.”

As they stand, the Bitcoin and Ether blockchains are simply too crowded for the average person interested in mining, but not for the dominant wealthy monopolies, according to Bhown.

While still hopeful, Bhown leaves one piece of advice.

“It’s definitely a minefield. Only put in what you’re willing to lose.”

It [cryptocurrency] is definitely a minefield. Only put in what you’re willing to lose. Ashutosh Bhown, junior

Planting the seeds of Chia

“Cryptocurrencies have the potential to outdo banking as we know it,” Bram Cohen, CEO and co-founder of San Francisco tech company Chia and inventor of BitTorrent, tells Verde. “The security on credit cards is horrible and slow even on the standards of how long it takes to make check out happen. They [credit cards] don’t give you full receipts, and they don’t give you the kind of control over recurring billing that they really should give you.”

However, the constant run of machines consumes extensive bouts of energy, which causes concerns for bills and the environment.

These issues are precisely what Chia is working to resolve.

“Our [Chia’s] process involves a disk space rather than [the] burning of electricity,” Cohen says.

According to Cohen, this process, dubbed “farming,” aims to alleviate energy consumption and in turn reduce negative press surrounding cryptocurrencies’ usage of electricity.

“The goal of the whole thing is really to enable commerce, as I see it,” Cohen says. “I don’t think there’s anything particularly different [with] the roadmap for Chia as to what — in my opinion — should be the roadmap for Bitcoin.”

This includes the possibility to transfer funds more cheaply and with greater speed and security compared to the current state.

“Making a better version of it [cryptocurrency] that’s readily accessible to consumers is something that would impact people’s daily lives in a very real way.”

We’re only at the beginning of this cryptocurrency era. Dan Boneh, cryptography professor

Bursting the bitcoin bubble

Mining, investing, improving energy usage and the transaction process; in corporate offices and in the classroom — what’s next for cryptocurrency?

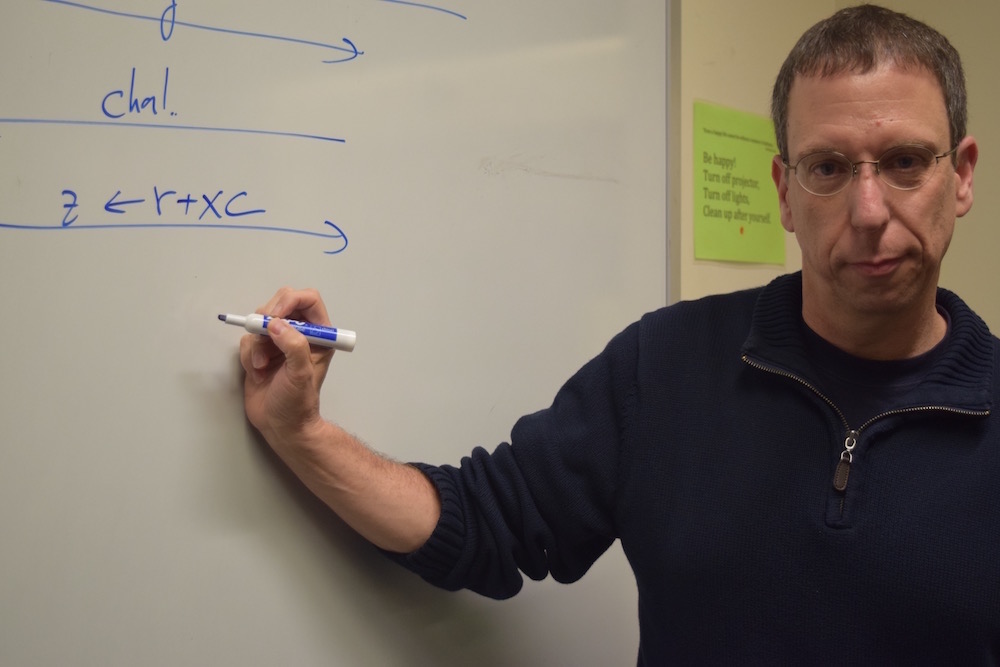

“We’re seeing quite a lot of companies leverage the fact that blockchains exist now to do things that we were never able to do before,” says Stanford cryptography professsor Dan Boneh.

Reimagining the concept of proof, for instance, isn’t too far off in the future.

“You can imagine that your [academic] transcript could also be registered on the blockchain,” Boneh says.

“The broad range of applications of this technology is still in the future,” Boneh says. “We’re only at the beginning of this cryptocurrency era.”